2009

Directed by Takeshi Koike

Written by Katsuhito Ishii, Yoji Enokido, and Yoshishi Sakurai

My impression is that Redline has maintained its minor legend in the fourteen years since its release; and don't tell me if it didn't, since if it hadn't, the world would be too profoundly unfair to go on in. Selfishly, however, I don't know if I'd want that legend to be more than minor, when it's something of the perfect cult movie, so ultra-niche and so fucking bizarre it's barely comprehensible; I don't know if anyone besides animation aficionados deserves it. In many respects it's exactly what you'd suppose that someone who doesn't know much about anime imagines anime is, and I guess they'd be right since it is indeed anime, though it's somewhat far afield from the typicalities of its industry and its form. It's one of the more batshit, formally reckless animated features ever made; if it is an exemplar of Japanese animation, it's because it prompts as keenly as virtually any Japanese cartoon ever made the questions that the most robust examples of that nation's first-in-the-world animation industry can raise, namely "how did human beings make this?", "what the hell is this?", and "why?"

Redline's first mover wasn't its director, Takeshi Koike, but its chief writer, Katsuhito Ishii, principally a live-action filmmaker who created Redline as something we could call a lark; and despite its status as a famed passion project, it miraculously remains the most whimsical of larks. Ishii relates his inspiration in the form of a just-so story, recounting the time he spent as a young man in Sonora, CA, USA—he doesn't pin it down, but my guess would be "in the late 1980s"—where he found himself bewildered by American car culture. He mentions a neighbor who spent all day with his face stuck in an engine, and Ishii wondered what kind of movie it would take to make this gearhead pay attention. History does not record whether his neighbor ever saw Redline. I hope so.

Ishii came to Koike at Madhouse, who'd previously worked from Ishii's script for his training-wheels OVA, Trava: Fist Planet. Joined by two more co-writers, they fleshed out Ishii's scenario into Star Wars mashed into Death Race 2000. (Trava had previously used a "sporting tournament in space" conceit, and, y'know, Redline is an argument that maybe everything should.) If you prefer, we can call it Speed Racer mashed into sci-fi space warfare anime like the Gundams or (throwing a dart and taking my chances) Legend of the Galactic Heroes; but it feels like the "American car culture" aspect bled through everything, and it did so to such an extent it's probably a better reflection of American comic art, American album art, and European magazine illustration than anime alone (and even as far as anime goes, it feels like its principal influence is Cowboy Bebop space noir, for there's some serious Spike Spiegel lifts in the protagonist's character animation). It's more all of those, anyhow, than "American car culture" such as that culture ever existed outside the mind of someone having a stroke during a double-feature of American Graffiti and Days of Thunder; but now, having been flogged through a whole gauntlet of Japanese animation tropes, it's been exoticized to the point of surrealism and near-unrecognizability. Let me be clear: I mean this, absolutely, as a compliment.

So Madhouse gave Koike his feature directorial debut, and, for whatever reason, they gave the barely-tested filmmaker carte blanche, with no particular deadline, or fastened-down budget or, apparently, oversight, since it was something like six years before anyone noticed Koike and a core team of about fifteen were still working on this one movie, whereupon Madhouse finally told them to hurry it up already. Koike was in fact almost done—just in time for Madhouse to tout the achievement that Redline represented, with every frame of the film done by human hands (a slight exaggeration, as it's digitally-painted and there are certainly effects animations that are computer-manipulated), which allowed Madhouse's marketing team to tout the 100,000 hand-drawn cels that went into the film as proof of its makers' craaaazy commitment.

This is a number that sounds more impressive than it should: many animated films are in the ballpark of 100,000 hand-drawn cels—I assume Fantasia is more, Dumbo substantially fewer, but Akira, which may set the record due to the unique fluidity of its animation methods, clocks in at about 160,000 (and if one wants to be impressed, there's Loving Vincent, which involves 40,000 Vincent Van Gogh paintings)—but by 2009, if not long before, an animated film that eschewed virtually all computer assistance, especially in the animation of rigid objects, was a singular rarity at any industrial-grade level of production. Hence, maybe, why tossed-off opening text declares that in this universe, sci-fi auto racing is itself a throwback—screw those newfangled "hovercars"—and hence, maybe, why our hyper-greaser hero is a throwback even amongst throwbacks, driving a futuristic supercar contained within the shell of a meticulously-maintained and frequently-restored Pontiac Firebird Trans Am of an unspecified model year, whose appearance suggests that Ishii hadn't actually seen a Pontiac Firebird Trans Am since living in California, but it's the cool thought that counts. Hence, maybe, why the villains are mechanical men. In any case, the "number of frames" doesn't become quite mind-blowing until you see what that Koike's team drew by hand.

This is the world of Redline—I don't think it gets a more formal name, but this movie, despite having much to exposit, and therefore often obliged to do so, still resists exposition like exposition makes it want to puke—but the Redline is the galaxy's most prestigious race, the finale of a tournament season built up to by several other also-color-coded races. So let's meet our pompadoured hero, "Sweet" JP (this is the kind of movie that cannot have you distracted by subtitles, nor does it give you time to read them, so I shall credit the English VA of the dubbed version, Patrick Seitz). JP has managed to work his way up to the Yellowline race, despite his underdog status, and despite his refusal to use weapons, like most of his colleagues do. He doesn't actually win—he's beaten by a daughter of racing aristocracy, Sonoshee "Cherry Boy Hunter" McLaren (Michelle Ruff)—but he does come very close. He would have won, if not for his scoundrel mechanic, Frisbee (Liam O'Brien), who's in deep with the mob and uses a small explosive to sabotage his driver right at the finish line, netting a small fortune for his mobster masters, for himself, and even for JP—but costing JP the thing he truly craves.

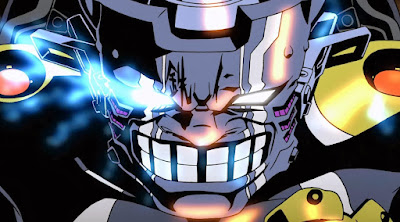

Yet, as fate would have it, several drivers drop out of the Redline race, for the galactic racing authority has decreed that Redline shall be held on the pariah planet of Roboworld, which in turn openly declares they don't actually want the race and will kill the racers if they come. Sovereignty, schmovereignty: the upshot is that JP's invited to serve as a replacement, and obviously he's not saying no. So off he and Frisbee go to a demilitarized moon full of squalid refugees, the staging area for the race, rebuilding their Trans Am with the help of junk dealer Mole (Steve Kramer). Here, JP has the opportunity to meet Sonoshee face-to-face—for the second time, but she wouldn't recall the last time. We meet a few other competitors—the one who matters most/is the raddest is Machinehead Tetsujin (Michael McConnohie), a cyborg, but, think fast, not a cyborg like the cyborg inhabitants of Roboworld are cyborgs—and then they race and try to kill each other, while the Roboworlders try to kill all of them, but there's something more than just a rivalry between JP and Sonoshee. But how will they square their equal desire to win and love with the violence of their contest?

So, like, some of that made sense. There's obviously nothing too difficult with "space race," and the character drama that flows out of the competition more-or-less makes sense. But then there's the premise, the whole "let's do a cross-country race in Space North Korea for no apparent reason while they try to murder us!" thing. My best guess would be (this could even be the "reason" within the narrative) that the race is simply more exciting and fuller of explosions than it would've been otherwise. That's, you know, whatever, but given their instrumentality it's shocking how much screentime is given over to Roboworld, and to Roboworld politics, in this 102 minute film, to the extent that I feel like the actual goal must be parody, first of those who would meld machine and man (i.e., those who would use CGI), then of sci-fi anime generally, something suggested by the Roboworlders' cod-grandiosity and how they're explicitly incompetent at everything they do, constrasting with the merely implicit incompetence of the villains of Japanese afternoon fare for boys; the idea seems along the lines of, "war cartoons? who cares about war when you have a hand-drawn hot babe and a bitchin' Trans Am, you pussy?" (The lead competitor, meanwhile, is named Machinehead Tetsujin, after the progenitor of the mecha genre, which was presently heading into frictionless, sometimes-uncanny CGI territory.) It's a dry parody, if so, so perhaps it really is just one more hat to put on a movie that's already hats piled atop one another in every way its makers could pile them, a story that even Ishii cheerfully admits "is kind of dumb."

That cheerful dumbness is, very obviously, the foundational reason this film exists: to be a sensory overload machine where everything is the coolest and raddest and metalest that Ishii and Koike could make it, blasting ideas and visuals and sometimes just nearly-abstracted colors and curves into your face, as rapidly as their animators can draw 'em, which wasn't very rapidly at all, but that's the magic of cartoons. It's the kind of movie that has an entire epic sci-fi monster battle, at a complete tangent to the space warfare plot, that was already at a tangent to the actual plot. If we're being severe, as criticism should be, it's incumbent on us to acknowledge that for a film dependent on racing, the middle stretches on for a good hour without any racing. (The other severe thing I have to say concerns James Shimoji's score, which, fittingly, involves shredding guitars, but I wish it were mixed higher and less resembled stock music.) But even when it threatens to get boring and bogged down, Redline simply invites you to look at it—look at these designs! effects! tits! crowds of freakish extras roiling in hypnotic movement loops! It hits you with an overwhelming sensation of everything happening at once, because it's all happening much too fast to happen in any rational order. Even in the "slow," "story" scenes.

And what design it is: even the least-enjoyable thing in the movie (Roboworld politics) comes with terrifically badass design, and the film's a constant series of demented discoveries of whatever was happening in the imaginations of Ishii, Koike, and its character designer, a fellow named—what's all this, then?—Katsuhito Ishii. That time in America must have been formative, and Ishii must've had a pull-list a mile long at his local comic shop: there is an astonishing amount of Jack Kirby here, but it's Kirby already mediated and modified by his successors, American and European alike, and I would love to ask him if he's a Keith Giffen fan—the existence of a whole "magic planet" that provides a pair of racers even more fan-servicey than Sonoshee seals it for me, that this dude had to have very specifically been reading Legion of Super-Heroes and probably during its Five Years Later Era, when the 30th Century of the DC Universe had gotten weird, gritty, and arty. (There are, likewise, a couple of racers that are more-or-less directly "Batman and Robin" and a couple of others who are only-slightly-less directly "the Red Skull" and "Beast the X-Man." Plus two characters literally from Trava, for fun.)

Extravagantly detailed characters are not always the case for anime; it's usually extravagantly detailed backgrounds, which Redline has, but it's mostly wastelands so desolate that it's functionally graphic abstraction even when it has a bunch of lines on it. But there seemed to have been effort to make these characters as baroque as possible while still being sublimely iconic, and never moreso than with JP—well, never moreso than with Machinehead, who's so fucking awesome, but he's not our hero. (JP's unmistakable silhouette, however, is a crucial plot element, which is unbelievably amazing.) The most aggressive aspect of the design aesthetic, however, besides what I'd struggle to describe less generically than "weird alien shit" (e.g., Mole is a hexapodal humanoid, and animated with significant thought put into how a hexapodal humanoid might move) has got to be the oily black stains of shadow all over everything. It's like chiaroscuro if chiaroscuro had no particularly concrete relationship with light sources—what should be mild shade gets thrown into stygian darkness here, and even the drop shadows (to the extent the movie even needs drop shadows now, and it only occasionally uses them) are black pits. The contrast is bold and that's worthwhile for its own sake, making the bright day-glo colors around them pop even more; yet as anti-realist as it is, it even brute forces the character animation into an illusion of three-dimensionality, which is extremely useful given that there's a whole racecar eroticism thing going on, and the film supposes that you should think of JP and Sonoshee as creatures of flesh. (There's a tit shot that exists principally just to demonstrate they can do nudity—it comes with a meta joke about hypocrisy I find dopey but quite funny—and there's even a tiny little indentation shadow inside her nipples, which is the kind of detail you don't see in your average, everyday perv anime. One wishes the tit physics were more functional, but if the idea is "these are ridiculous fake VHS-era porn tits soldered to Sonoshee's chest," would that be wrong here?)

Beyond the characters, yet exactly as important, there are the vehicles—and there's overlap there, Machinehead being his own vehicle. They're a bizarre collection of the most expensively-complicated toys, and this is where that drawn-by-hand thing starts to feel like Koike, though neither the project's instigator nor the originator of its most aberrant ideas, actually was the insane one here, for insisting that it could be done. But it did get done, Koike's stated rationale being that hand-drawn action meant complete control, and that's a case to make, but what it does, to my mind, is infuse these preposterous machines with personality, identifying them as extensions of their drivers (an absolute narrative necessity in these circumstances, where there's practically no narrative at all besides a dozen fragments of backstory slammed into the ongoing chaos of a tournament movie), and moreover allowing the cars to surge with power and speed and, remarkably, actual vitality. (Machinehead is like a bomber plane flexing with metal muscle combined with the torso of a cosmic god, propelled headlong toward the finish line with nitro flames blazing from his ass.) There's something organic about all of them, though, and not just Machinehead—not so much in a gross or horrific way (though horror is another toy Kokei's ecstatic to play with, and depending on your tastes Machinehead is horror), but there's an actual squash-and-stretch quality to these mechanical, notionally "rigid" creations, that gives them genuine expressiveness, even if the expression is usually, "fuck, that's fast."

It ends up in a sort of hyper-stylized singularity—one thing I haven't mentioned is the strategic use throughout of hand-drawn distortion to render the concept of "speed" as a psychedelic experience, culminating in characters almost literally melting into one another—and it's fun to recall that the Wachowskis' live-action Speed Racer is separated from it by barely a year. It's kind of glorious to see the equally-nuts, completely-distinct ways two different creative teams at the top of their art arrived at the same point—a finish line imagined as, essentially, the holiest possible orgasm—and between the two it's humbling, because they make me feel like there's still an infinite universe of pop art stylistic insanity yet to be explored. Orgasm-wise, Redline has the edge of actually being a love story—that might be its primary genre, beyond sci-fi, maybe even beyond racing, and while there's a ton of bullshit in this film, its emotional logic is pure and pristine, without even stressing the two sides of its emotional arc beyond what it needs. JP is the one character who gets flashbacks, memories emerging from the white-hot shroud of a desperate childhood, and I'm extremely taken by one of the keys to his yearning, the life-changing thumbs-up he once got from his racing idol, driving off into what appears to be the heart of the sun with not one but two hot babes, a symbol of unachievable mastery (possibly my single favorite set of frames in the whole movie comes here, the bit where the great racer somehow makes out with both of his chicks, literally at once—it's just such a creative way to denote the crass elementalism of the milieu in a way that still feels as poignant for JP as it is jokey for us, and it's one profoundly good use of animation to depict the subjective and surreal). Anyway, the not-even-remotely-stressed part is what became of his childhood hero, and JP never actually does learn who his idol is now. He is, instead, allowed to keep his innocence, along with the simple childhood crush he had on the other racer who looms large in his memory, whom he never could have expected to be remembered by, and who indeed doesn't—the one he may not have realized he's been questing for all this time. Calling it "pure adrenaline" is a great pullquote, but this engine's got more juice than that; the final shots are the perfect encapsulation of the film's whole reason for existing the way it does, that what matters is human.

Score: 9/10

Hey I just watched this one! I really enjoyed reading your review. (In fact, I read it a few days ago, and quoted your figures on cel counts in a podcast I recorded about the movie. Hope there's at least some basis to what you wrote, haha!)

ReplyDeleteI'd probably land at 8/10 of ten scale, and a low-ish 7/8 on Is It Good, mostly for pros and cons you cite. Also, as much as the movie is random bullshit, it's COHESIVE random bullshit, right up until Funky Boy, which really threw for me a loop even as I loved how well it was executed. Felt like he wanted to make a kaiju movie but only for 8 minutes worth of screentime.

The 100,000 frames thing is so commonly repeated I don't know where exactly it would've started, but I'm pretty sure they made a deal out of it and it's mentioned in the making of featurette. Regarding other movies' cel count, just multiplying on-twos animation for Disney by their runtimes would sometimes yield higher numbers, though admittedly that's a crude way of estimating, and it's entirely possible and in fact even probably that Fantasia might have fewer cels of, like, actual character animation (but would still have some manner of effects animation). The numbers on Loving Vincent are hard and presumably trustworthy. I kind of wish I'd footnoted that number of Akira, because it seems like a really high estimate but it's not just 124 X 60 X 24, which would be the upper bound even if one stupidly assumed the entire film was animated on ones. Hence I must've got it from somewhere--and, indeed, I did, a fandom.com article as well as several other places. It's annoying, though, because auditing that, it seems like the latter examples might be just quoting an unsourced claim by the former. Well, I hope they got it from a somewhere, like a making-of or commentary or interview or something. At least it's not an important fact like the prevalence of colon cancer in a clinical trial or whether Hunter Biden is secretly me.

DeleteAnd yeah, the bioweapon stuff is so weird. But so's, like, magic spells. I'm gonna read some Legion of Super-Heroes.

Of course you also get people saying "X number of drawings" sometimes and what the hell does that mean? The Little Mermaid, just to pick something I know the animator pool of off the top of my head, is probably in the low seven figures for drawings (like eight figures, if you count bubbles!), but probably 60,000 frames.

DeleteAnd as for Disney stuff, or any stuff, I think it's a mistake to assume literally all character animation will be on twos, because a lot will in fact be on ones.