1941

Directed by Edward Dmytryk

Written by William Sloane, Robert Hardy Andrew, and Milton Gunzberg (based on the novel The Edge of Running Water by William Sloane)

The 1940s proved significantly more fertile ground for Spiritualism on screen, fake and otherwise, than had the 1930s; and while it's possible that the newly-increased rate of ghost production as a result of World War II had something to do with it (in the same way that the vogue for celestial bureaucracy films like It's a Wonderful Life or A Guy Named Joe has everything to do with World War II), I can't really find evidence that Spiritualism itself got any enormous boost in popularity along the lines of the one it received following the Great War and Spanish influenza pandemic, and so if I had to hazard a hazy, inexpert guess, I'd say it was a matter of the burgeoning genres of detective movies and film noir, which had a need for scuzzy, exploitative villainy, and phony spirit mediums provided excellent raw material. (I suppose it is possible that 1940's You'll Find Out, a horror-comedy about a phony spirit medium, was simply a big enough hit to remind filmmakers that some people claimed they could talk to the dead, and you could do neat stuff with that in the pictures.)

What this means for our present purposes, however, is that following Spiritualism's Sound Era debut in 1933's sci-fi-inflected horror film, Supernatural, Spiritualism on screen largely missed out on crossing over with the 30s' decade-defining brand of horror, pulpy mad science. And this is a pity, and a curiosity, because Spiritualism had been linked to pseudoscience—and even genuine science, albeit genuine science that could sometimes still be so open-minded its brain fell out—since the late 19th century, when Spiritualists themselves helped found the Society For Psychical Research, before large numbers of them, including a furious Arthur Conan Doyle, turned against it when it became clear that the scientific investigation of parapsychological phenomena mostly just tended to prove that parapsychological phenomena didn't exist and that a lot of the people claiming they did were con artists. Thus 1941's The Devil Commands is a little special as a true follow-up to Supernatural, arriving at the last possible moment it could, tossing a pulpy 30s-style mad scientist (played by Boris Karloff, no less) up against the Spiritualist veil, which he pulls down around him, winding up flailing about and tearing at it with his 30s horror movie version of "rationalism," which mostly amounts to approaching any given problem with aggressive buzzing noises and devices that produce electrical arcs. The terrible thing is that the movie that came out of this is at least as disappointing as it is great.

You don't have to watch that much 30s and 40s B-horror to glean a sense of their common weaknesses: they're often the result of less-than-fully-engaged artists, especially on the screenwriting side, but frequently enough with the directors, cinematographers, and actors; relatedly, they're more often than not moronic and condescending, because they've been pitched to children and childlike adults; they don't have time (either the runtime or, it would certainly seem, the development time) to do even modestly ambitious concepts, so when they do modestly ambitious concepts anyway in order to draw an audience, what you wind up with (Universal Horror in the 1940s is lousy with this) are stories that just halt, or get completely derailed into the first thing anybody could think of that would end them, rather than a nice, proper dramatic climax; and they're cheap, so their non-climaxes are often crappy and perfunctory, their budgets having been exhausted already in getting there.

And I won't say that The Devil Commands is immune to any of these problems, exactly—not to spoil too much, but while produced at Columbia, its climactic violence is entirely consistent with Universal's playbook, except, insofar as it's contemparenously-set, this movie's angry mob of rural peasants is bound to have electric flashlights instead of torches—and yet it possesses every element necessary for not just a good but a powerful and intelligent story about a scientist getting sucked into Spiritualism. More than this, it spends the majority of its little 65 minute runtime pursuing precisely such a powerful and intelligent story, delivering some delectably unique horror film imagery along the way and getting a great deal out of its excellent topline cast, and then it just... flubs it, inexplicably so, in its final moments. And it's not even money or time here—the movie is cheap, of course, but these final moments don't even betray that cheapness, given that they manage to drop a collapsible house set upon that aforementioned angry mob, which couldn't have been that cheap and I don't suppose they were positively obliged to do it—and the screenplay, though imperfect, certainly seems aware of what it's doing and, just as important, what, heretofore, it's already done. But then it up and decides it's simply not going to be as high-impact and emotional as it should be, or, really, at all.

So we begin some months or years down the line, approaching a sinister-looking (miniature of a) decayed and half-destroyed seaside mansion somewhere in New England, which we learn was the home of a scientist, Dr. Julian Blair (Karloff), thanks to the sad voiceover narration of his daughter, Anne (Amanda Duff), which will wind up being the most obvious indication that the screenplay hasn't been as thoroughly polished as we'd have preferred, because basically every time there's any lull in the story, Duff's voice is going to pipe back up to somberly narrate things that are by and large stupidly obvious, along the lines of saying aloud, "after his disgrace, my father bought the house I showed you twenty minutes ago and which you now see him living in." But for now, it imposes a mood and a mournful distance upon the affair, which began one night back at Julian's university, as he was giving a demonstration to his peers of his progress into his parapsychological research. Via a machine that reads the brain's electrical impulses (and appears to simultaneously deactivate the overhead lights when in operation, for atmosphere's sake), he has shown that human brainwaves are unique, and that, potentially, they could be deciphered for meaning, though even he'd probably admit this is some heedless futurism as yet. His wife Helen (Shirley Warde) arrives to pick him up to meet their daughter for her 20th birthday, and on the way to the train station through the pouring rain, Julian pops out of their double-parked car to get her birthday cake. Thus is he spared from harm while another car plows into Helen, killing her.

But as Julian wanders around shellshocked in the aftermath, retreating to his lab for privacy, he absentmindedly fiddles with his machine, and is astonished to discover that it's reading something that shouldn't be there—his wife's uniquely identifiable brainwave pattern. His colleagues frown, and his daughter outright scowls, but he knows what he's seen; and an assistant, Karl (Ralph Penney), believes him, because he's talked to the dead himself. He drags the doctor to his spirit medium, Blanche Walters (Anne Revere); Julian sees through her scam in minutes, though when he asks her about the powerful electric shock he received during their seance, she coldly but honestly admits she doesn't know what he's talking about. Following some tests, he realizes that there is something to her powers, and with her, he wonders if he really can tune into the great beyond. Two years gone by, he's almost ready, and at every step he's compromised and allowed his grief and Blanche's bad influence to corrode what remained of his moral compass—starting with an accident that leaves poor Karl a mute imbecile—so that, degree by degree, he's become a ghoul, a murderer, and a monster with only one goal, to hear his wife's voice one more time.

By today's standards, this isn't any shoddy B-movie plot, it's damned near what we'd call "elevated horror" (except it's 1941, so it's still dedicated to being entertaining), and it already has the cast to elevate it. There is a necessary brusqueness to The Devil Commands, so we're not getting too nuanced in these performances or characterizations; but Karloff is tolerably great within the couple of dimensions he gets, gruff and wounded because nobody believes him, and thereby completely isolated in his mourning, and pathetic when he realizes he's gone too far, frequently expressing apologetic sentiments, but apparently sincerely believing that he has no real control over or even responsibility for his various horrible acts and even more horrible omissions. And Karloff probably isn't even the best performance the film offers, or at least not the most magnetic: Revere's cruel spirit medium winds up even more impressive, her snappish line deliveries, stony features, and chilly affect (hell, even her 40s hairstyling evokes satanic horns) conjuring up an indelibly good piece of screen villainy, absolutely drained of all humane feeling but the very dregs, mostly just a vague, omnidirectional resentment that life has given her nothing but the power to survive off the exploitation of credulous rubes even more contemptible than she is. It's an attitude that has not really changed as she's worked her way into the dominant role in her partnership with our good doctor, which winds up an (unstressed) mockery of a nuclear family to replace the wholesome one Julian had before, complete with infantilized Karl. (It's enough of a mockery that after living in the same house for two years, mom and dad still refer to one another by honorifics and surnames.) Everyone else in the film is kind of actively terrible, but these are absurdly good performances for a film that's in the same industrial bracket as, say, a Mummy sequel, and it makes you wonder if Revere missed a calling in horror (she won a well-deserved Oscar a few years later in very-much-not-horror) because for all that her performance is pitched as grittily realist, it's still got a fun horror-flick bite to it; in Karloff's case, his performance is still top-tier even in context with other, better-remembered Karloff movies of the same vintage.

Director Edward Dmytryk is not necessarily following suit, and that's fine: the goal of The Devil Commands is to be a junky little shocker about wild ideas, not a grief drama, though one could potentially imagine a desire to thematically buff up this B-movie with this director, who was presently working his way up the ladder from his beginnings as an editor (notably for Leo McCarey), but who's most famous for making a credible Best Picture bid for 1947 with a film noir, Crossfire, and then getting blacklisted. He makes at least one gesture very consistent with a director taking his B-movie seriously as a drama, and consistent with being an inventive film editor by training: there's a beat in the grief-stricken stretch between the film's establishment of Julian's pathos and its full-tilt commitment to mad science horror that comes off strikingly modern, where it's Duff's daughter who's entering a room, but the insert shot actually uses Warde's dead wife.

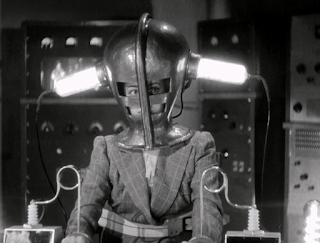

There's not any experimentation with that kind of subjectivity otherwise, and what Dmytryk's doing with the rest of it is just a very solid work of craftsmanship, albeit with a particular vision for the material; maybe it's just a result of this Columbia B-picture being cheap (and not having access to the institutional knowledge they still retained at Universal), but I prefer to think that Dmytrk and cinematographer Allen G. Siegler were carefully going out of their way to "de-Expressionize" their shadows, while still having just as many as any other horror movie, rendering something out of their no-less-promiscuous use of darkness that was far less mythic and so much more sordid than the mainline of 30s and 40s horror cinema, with a lot of high-contrast photography that emphasizes the true grimness of this scenario, and which even (maybe intentionally, maybe not) emphasizes the DIY kludge of Julian's scientific horror. The final form of his machine is an extraordinary piece of low-budget design, anyway—even making a legitimate strength out of being low-budget, considering, after all, it is just what these two freaks have whipped up together in an attic—and I don't know if the credit should go to art director Lionel Banks, who in 1941 probably represented the most A-list crew member on the production (he was Capra's guy at Columbia), but who also had no experience whatsoever in this kind of morbidity, or if the credit is more properly attributed to the uncredited prop department personnel (three men, presumably brothers, sharing the surname Dallon), but what we eventually get is an outstanding collection of lashed-together foil and wires that looks like cheap sci-fi serial spacesuits and takes on the form of an utter perversion (and utter inversion) of a Spiritualist seance that is skin-crawlingly creepy when it gets turned on, and begins, shudderingly, to move.

I have, in the main, been describing a very good or even excellent movie; and I hope that gets across the feeling I had, of watching a very good or even excellent movie, that suddenly stops being either in the last five minutes. The short and non-spoiling version of it is that, eventually, Anne is going to head out to her father's seaside mansion, one step ahead of that flashlight-wielding mob; and the movie just sort of starts crumbling as a functional narrative object. I swear to God that they actually forgot to film a scene, or the dumbest person in a position of authority over this film removed a scene in order to hit that 65 minute runtime, and this scene, which I repeat is not actually there, is the most important scene in the fucking movie. There's a pretty strong sense that it's missing two scenes, in fact, but the upshot is that despite wasting a whole lot of time with Anne's voiceover, and ancillary characters like Julian's ex-assistant (Richard Fiske) and an all-too-level-headed sheriff (Kenneth MacDonald), they don't manage one jot of material inside the story itself that even appears to suppose that Anne might also have feelings about hearing her mother's voice again, or that elucidates, at this extreme of horror and possibility, how Anne's relationship to her father has changed, though from what is here, it's clearly been struck with a downright tectonic shift.

The finale has all the superficial storm-and-thunder goods—loud howling sound design; the prospect of a scientific or even supernatural power destroying all those who meddle with it and also anyone standing near them; even the tantalizing suggestion that in the end Julian might or might not have succeeded in his unhallowed goal—but it doesn't seem to realize that this climax ought to have rather strong, specific emotions attached to it, or that it's even an emotional culmination for our antihero and his daughter in the first place. As far as horror goes, and I'm not at all saying I would've preferred this, but neither does it pay off on any of the screenplay's idiotically-phrased (but quite unmistakable) foreshadowings of something worse than death lurking beyond the veil Julian seeks to pierce. (You know, something that might seriously justify a title like The Devil Commands.) Instead, it's kind of just nothing, and it launches into one last Goddamned voiceover, though, for all I can tell, it does so mainly because the film began with one; and I am honestly at a loss as to what to do about a film that just disintegrates right before your eyes the way this one does.

Score: 6/10

No comments:

Post a Comment