1961

Written and directed by Curtis Harrington

Throughout the course of this retrospective on the Gothic (sometimes very nominally "Gothic") horror films of American International Pictures (sometimes not even nominally American International Pictures), I have been quite intentionally vague about what my criteria are. But two names have pretty much always ensured my attention: Roger Corman and Edgar Allan Poe. Corman, of course, is famous for, amongst numerous other things, the eight adaptations of Poe he did for AIP, and I have made a big deal about the way the company continued their Poe "series" for five more films without Corman and, remarkably, without Poe, with 1965's War-Gods of the Deep (aka City Under the Sea), 1968's The Conqueror Worm (almost invariably called Witchfinder General today), 1969's The Oblong Box, 1970's Cry of the Banshee, and, in the end, 1971's Murders In the Rue Morgue all to some degree tying themselves to Corman's octology, not one of which you'd identify as an "adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe" if the movie hadn't told you. (And this is not counting 1969's Poe anthology Spirits of the Dead, which I wish to extricate myself from because it is almost entirely a creature of continental Europe, not even British-American like half of the ones we've done here, and the Eurogothics distributed by AIP amount to one enormous can of worms; nor is it counting Vincent Price's AIP-TV Poe recital, 1970's An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe; and it is not counting The Terror, though we did indeed cover that debacle already.) What this has left out, however, because I didn't know it existed at all until two days ago, is 1961's Night Tide, which suggests that AIP might not have even started the practice of throwing Poe at movies that had not asked for it.

The title is from the poem "Annabel Lee," one of Poe's infinite number of works on the subject of lovers separated by death. It is at least nebulous if AIP were the ones who insisted on that, since while they distributed it, they didn't produce it, Corman did, in his role as the head of The Filmgroup (alongside his brother, Gene), this being an entity that, long before New World, represented Corman's first attempt at B-movie moguldom. Filmgroup mostly served to produce films Corman wasn't directing himself, and the ones he did direct for Filmgroup are at a level of industrial backing and artistic commitment generally below his work for AIP, which I don't necessarily mean as a complete dismissal, but there's not really a way to say it without it sounding that way. And I can think of one exception to that rule anyway, at least on the artistic commitment front, in the Corman brothers' 1962 anti-segregation film, The Intruder.

In the case of Night Tide, however, what Filmgroup were producing was a script by Curtis Harrington, former film critic, Kenneth Anger associate, and Thelemite, which he'd written all the way back in 1956 (and so some time before pinning Poevian language to it would have been a branding move), this script being called, at the time, The Girl From Beneath the Sea. The title gets across the content of the movie reasonably well, but I think we can agree it isn't as pretty. It is not, of course, an adaptation of "Annabel Lee"; I don't know how you would adapt "Annabel Lee," unless, I suppose, you transformed its metaphor for tuberculosis into an actual, literal army of angels out to kill a woman for being too sexy. Either way, five years later, Corman gave Harrington the job of directing it (his first "real" movie), and I'll admit, it is altogether possible that the title change had already occurred, given that Corman already liked Poe (the Poe films were his idea, after all), and the use of an oblique allusion instead of just calling it Annabel Lee (already not the most famous Poe poem), and renaming the heroine to fit, doesn't outright scream "exploiting the opportunity presented by The Fall of the House of Usher's success" the same way the rest do. Moreover, Poe's verse only appears at the very end here, as a coda, and get this crazy shit: it is entirely germane, reflecting and enriching the film it's been appended to. After seeing so many forced Poe references on behalf of AIP's horror towards the end of the decade, it's kind of amazing. The actual story, on the other hand, is based on Cat People.

That's not entirely fair, or at least the specifics are different enough. And so, at the waterfront in Santa Monica, CA, arrives a young USN seaman named Johnny (Dennis Hopper, not his first real movie, but his first real lead, coming after ruining his first go at a studio career and stumbling his way in the direction of Corman's New Poverty Row). Johnny is alone and lonely and wanders into a jazz club where he surveys the landscape, and fixes upon Mora (Linda Lawson), also alone. She protests, not all that strongly, that she prefers it that way; but she's willing to accept his company, if for nothing else than to get away from the older woman who's shadowing and frightening her (Marjorie Cameron, another Anger associate, and I insist you look up her biography, for she had one wild life), for reasons Johnny doesn't go out of his way to extract from Mora. The two strike up a tentative little romance, and he returns to have breakfast with her in her apartment, above a merry-go-round, which itself is run by a nice bunch of folks, though one of them, Ellen (Luana Andrews), has some nasty suppositions to make about Johnny's girlfriend.

Johnny will eventually be told much the same thing except even more forcefully by Mora's guardian, and father in all but name, Captain Murdock (Gavin Muir), formerly of the Royal Navy and presently proprietor of the boardwalk sideshow Mora works at as a phony "mermaid" (her job, which Johnny politely suggests must be restful, involves laying around for hours at a time pretending to be underwater). You see, it's not gone unnoticed that of Mora's last two boyfriends, both of them have wound up corpses—this is as much as Ellen knows, and she tells Johnny, though she admits she has no reason to believe Mora had anything to do with it beyond the improbability of it being anyone else. Captain Murdock, meanwhile, openly warns Johnny that he'll be next, admitting that Mora killed each man in turn, because that's simply her nature, as Mora is of the same stock as the amphibious race whom Homer had torment Odysseus upon his journey home. Thus she could be called a "mermaid," but Captain Murdock would describe her as a siren, with all that entails. Johnny doesn't believe this, at first, but he's startled to discover that Mora absolutely does. He's already in love, so he balks at leaving the woman he loves to dissolve in her delusions. It won't go well for him.

So, "Cat People with a fish woman," like I said (and sometimes an octopus woman, albeit only in Johnny's hallucinations), but given a very fresh coat of paint in resituating the story to seedy dockside California, and one of the things that's very pleasant and inviting about the film is the sense of community Harrington manages to make out of his scenario, despite the very constraining factor of a tiny cast of mostly bad, or at least limited and inexperienced, actors. Initially this is by far Night Tide's biggest problem, and while I don't believe you'd identify Hopper as a future star on the basis of anything here, you certainly wouldn't on the basis of the draggy first scene, where he is overcooking Johnny's anxious yearning into irritating twerpishness, while Lawton evinces a clear inability to walk and chew gum at the same time in the sense of not so much playing the various layers of her character that will be revealed over the course of the film—disquiet over being confronted (we can tell not for the first time) by the creepy old woman, hesitance to bring another doomed man into her life—as she's playing what this scene looks like, or at least what it looks like in a script as inelegantly-written as this is on the matter, an active distaste for getting nagged and followed by a horny sailor.

Happily, from these unpromising beginnings the two actors, however clumsily and uncharismatically, find their way into some level of awkward chemistry that does justice to a humane depiction of uninteresting, not particularly bright young people liking one another—Lawton doesn't play "wary for a number of reasons" well, but she's not Godawful at "enjoying dates"—and while it's not distinguishing itself in any way that you might be willing to call it a swell romance, outside of its supernatural implications, there's no use pretending this relationship doesn't have those supernatural implications to rely on, so as to give its central dynamic some juice. It's even kind of surprising how rapidly the film blurts out "by the way, she's a sea monster," and Johnny spends by far the majority of the movie grappling with whether Mora actually is a sea monster, and what it means if she is, and the mysteries associated with that. It has a very likeable weird fiction cast to it that I personally respond to very easily.

More importantly, it looks better than perhaps it even should, and partly that's just thanks to the location shooting that captures a languid and easy-going, beachside vibe, a peek behind the curtain of the touristy fun of the boardwalk, with Harrington distilling a certain alienation out of it, so that you never forget Johnny is a stranger to it, and that everyone already here is just plain strange, not necessarily menacing—mostly they're very friendly—but off-putting. Mora, likewise, gets as much personality out of how art director Paul Mathieson (yet another friend of Anger) puts her apartment together, festooned with souvenirs from the sea, and dovetailing nicely with a script that can be good in a lot of ways, like how, at the conclusion of her breakfast date with Johnny, Mora snatches up a seagull that's been drawn to her side, not harming it in any way—she even comes off motherly—but making us more uncomfortably aware than her new boyfriend seems to be that birds don't usually act this way with people. The major factor, though, that makes this by far the best-looking Filmgroup picture I've ever seen (and I don't pretend to have an encyclopedic knowledge of their output, but we've all seen several if we're MST3K fans) is that it is, to the best of my awareness, the only one upon which Corman managed to deploy his trusty Poe cinematographer, Floyd Crosby. He's uncredited—for all I know everything I like is the work of its credited photographer, Villis Lapinieks, and I indeed assume a lot of the "easy-going, languid" location shooting is—but one can suspect that Crosby might be responsible for the scenes that most keenly recall this is horror and not just a clunky indie romance, particularly some grungily handheld, noirish treatments of the lights of the boardwalk fair, and the haunted atmosphere of Mora's mermaid sideshow. I'd bet a dollar the rather Cormanesque freakout Johnny experiences, where the most lurid imagery makes its appearance (along with some characteristic distortion effects), is Crosby's work.

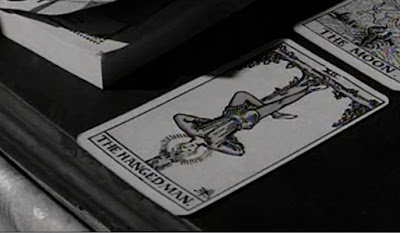

But who could say who did what here; in an optimistic false climax, Harrington and whichever photographer was at work that day manage some striking and disorienting imagery of the space beneath the piers, nearly rendering it a geometric abstraction, all vertical lines buffeted by darkness, which, whether or not he was merely a producer, feels like the kind of psychoanalytic notion that Corman would've liked. But then, I've mentioned the mystical side of its cast and crew often enough that you'd presume something of that bleeds through, and it does, most notably in a tarot reading that beats the socks off anything in Nightmare Alley, not solely because "tarot" is pronounced correctly, though that helps, but also for accuracy, if by virtue of practically quoting aloud A.E. Waite's The Pictorial Key to the Tarot (as opposed to, curiously enough given the Thelemite affinities, Aleister Crowley's Book of Thoth) to explain it. (This sequence also sums up the agreeable "community" aspect I noted: the local clairvoyant, "Madame Romanovitch" (Marjorie Eaton), expects Johnny to pay her like any other customer, but only if her new friend can really afford it.)

I said that's the most notable, but also the only part where it feels like Thelema, or occultism in general, is a truly valuable lens through which to view it, and I suspect Night Tide would be better if it did veer more towards its particular vision of the Hanged Man (or, in Thoth Tarot, depending on your aeon, the Drowned Man, can you dig it?), and the price he pays for the banishment of illusion. I was, anyway, liking Night Tide very much at this point and for a good ways thereafter, forgiving of all its weaknesses as a wobbly but nonetheless earnest and effective paranormal romance, until it just sort of sharts itself, whereupon it puts on a new pair of different, serious pants, and course-corrects from fairy tale to psychology to explain away some, but not all, of its mysteries. (The having-it-both-ways approach is where it really gets itself into trouble, honestly, threatening to just become completely incoherent in all the ways Cat People was graceful.) This is mid-century psychology, and maybe this is the Corman of it, but it seems to be very intent on ruining the fun, and by means that are not nearly as instantaneously intelligible as Harrington clearly believed them to be. And that's on top of this element being so aggravatingly contrived, but somehow significantly more stupid and prone to raising a 1001 nitpicky questions than "octopus chick" would've been. Yet I do love the mood of that middle hour, and I wonder if Night Tide will stick with me longer than the score I'm going to give it suggests; and man, that poster's terrific.

Score: 5.01/10

No comments:

Post a Comment