2021

Directed by Wes Anderson

Written by Roman Coppola, Hugo Guinness, Jason Schwartzman, and Wes Anderson

I believe I said upon the release of The Grand Budapest Hotel that Wes Anderson had, with that film, achieved his final form. I was wrong and I'm ashamed to have underestimated him, so while The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun outright dares all of us to make the exact same claim, I don't think I have it in me. There might not be any such thing as peak Anderson. He's in an asymptotic death spiral of twee nostalgia, perpetually approaching some unknowable point that will forever elude him because that's kind of his whole deal. I'll only say I can't imagine how he could take it further.

Going on fifteen years now, during the intervals between his live-action films, he's made a couple of stop-motion animations; his most recent anything was his 2018 stop-motion cartoon, Isle of Dogs. Somehow, as much as I like that film (and The Fantastic Mr. Fox before it) they don't seem to have quite the same substance as his live-action efforts; Dogs, as far as I can determine, really is just a straight-up lark. That's cool, but they don't do it for me the same way this does. I suspect that while they scratch some esoteric, handicraft itch, they don't quite do it for Anderson either. There's something deeper to his work when he uses real, flesh-and-blood human beings to make these movies where it feels like he's playing with dolls. It's become both a bit of a cliché, but also no less true, to claim that at least since Grand Budapest his live-action films have somehow felt more like somebody playing with dolls than the movies he made through the actual process of playing with dolls. Now more than ever; now we swing even closer to that unreachable point where substance and style meet, so that here they've been brought close enough that we might as well say that the substance is the style and vice versa. If they became any more unified, anyway, you'd wonder if your face would melt off. This penchant for digging out the bottom of his own well has made Anderson, to my mind, maybe the most exciting director we've still got going. Unless you don't like his style, or his substance, in which case it's surely made him the most insufferable.

This is not to say that The French Dispatch is my favorite; there's a chilliness to this particular exercise (or a mutedness to the sentimentality, to be more accurate; when I say "chilly" I don't mean "devoid of humanity," which it assuredly is not). I therefore somewhat expect it to be a lot of people's least favorite. I'm only given pause on that because Anderson's spent a long time separating the audience who liked him from the audience who just liked Rushmore. (I didn't realize till recently that I might be this Earth's single biggest fan of The Life Aquatic.) It's surprising but gratifying that so many people have been willing to come along with Anderson as he burrows further into his own shell, eager to show off his collection of vintage movie posters, or rare stamps, or Hummel figurines, or whatever it is that insular nerds like him would do, assuming he managed to convince somebody to come over to his house.

What strikes me this time about Anderson's nostalgia is that, continued box office success notwithstanding, he's outlived the era of his own revolutionary novelty, becoming a recognized master with an absurdly-recognizable style, and, as always happens, a bit of a joke in his own time. I'm surprised I haven't seen the phrase "self-parody" wielded against The French Dispatch, though I'm sure that, somebody, somewhere, has used it as an insult. I don't mean it as an insult. I mean there are actual elements of self-parody strewn throughout the movie, where he's gently mocking himself the way he's gently mocked his characters' fixations his whole career. It seems uncharacteristically self-aware this time, but there's no other explanation for some of the most successful gags in this very successful comedy, involving dissolve transitions into detailed and utterly pointless cutaway drawings of airplanes, except that this is Anderson's way of saying, "why yes, I have seen the spoofs, but you're doing it wrong and it would be much, much funnier if I did it for you." This specific visual gag occurs twice (at least), and even that's nothing on the (not-especially-well-) animated sequence toward the end, done as some hybrid between magazine illustration and Eurocomics, erupting at the beginning of a theoretically-exciting chase scene. This, I conceive, is Anderson telling us that he knows that his own style has become so extraordinarily static and locked-down and prissily meticulous that he can barely imagine chase scenes in live-action anymore; but he's also saying that he accepts this as a fair price for his unprecedented precision, his fussily-arranged fake clutter, and the reduction of his frame and camera to a set of austere and disarmingly-gorgeous right-angles. Well: add to that some uncountable number of other referential and self-referential gags, and you've got a grip on The French Dispatch, such as it is grippable.

It feels like an attempt to sort the faithful even further: here, the objects of Anderson's fannish affections are, maybe not in this order, middlebrow periodicals (specifically The New Yorker, though distinct in various ways, starting with "it's an American magazine published in France"), and French culture generally, but especially the French cinema of the 1960s. (Will it shock you to learn that this Anderson film is a period piece set in a fantasia of the mid-century?) The French Dispatch demonstrates maybe Anderson's most unique talent: he loves these things to pieces, and whether I love them, or even have any use for them, I can't help but love that he loves them. I don't know how he does that. I tend to find this kind of indulgence annoying; maybe it's because he loves that people love things, even more than he loves these specific things himself, and that's what I'm responding to. But for all the Nouvelle Vagueness, Anderson is irreducibly American. He still knows how to put on a show and somehow never quite gets lost up his own ass, even though "getting lost up your ass" is practically what his show's always about.

There's always a whiff of skepticism to Anderson's love of the junk of the past; as usual, that works its way into this film, in this way and that. So: The French Dispatch, like Grand Budapest, like the whole sweep of Anderson's filmography, loves these things in large part because they're gone; and so, most blatantly obviously, The French Dispatch is (predominantly) shot in Academy ratio. Maybe that's because the square(r) frame accentuates Anderson's square visual scheme. I mean, it does. But maybe more than anything else it's because it's old. To bring it back to the self-awareness thing, the whole film is suffused with the strange realization that Anderson's own pop-up books for adults will be (if they haven't already been) consigned to the same status as the things he loves—relics of a bygone and more delicate age, and, worse, that despite the immense underlying sincerity of his work, their post-modern fragility means that they might not survive some future artist's attempts to honor them as their own source of inspiration. If all great things must end in loving pastiche, and that's the Anderson rule, then somebody qualified—like Wes Anderson—best make the Wes Anderson pastiche while he still can. Anderson's even rarer talent, then, is to make his own self-regard this self-justifying.

To this end, we are invited to distantly consider the literary magazine spin-off of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, founded by Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray), the son of the newspaper's owner, when he went off on a trip to France one day and never returned, settling in Ennui-sur-Blasé (look, I laughed). As in Grand Budapest, The French Dispatch is concerned with paying homage to an institution, or the idea of an institution, and takes place (to the extent it "takes place" at all) long after its founder and custodian has died. (Though it is happier to celebrate the life of its fictional publication, The French Dispatch is, at least conceptually, pointing in the direction of being sad about the long decline of the written word, and, by implication, a significant unease with its successors.)

Also like Grand Budapest, The French Dispatch revolves around probate: Howitzer's last will and testament requires that the magazine be shuttered with his passing, which, in terms of "self-regard," just about takes the cake. Howitzer's conditions do permit, however, the publication of one last issue, a compendium of three of its best and most representative pieces, and thus is The French Dispatch (the film, that is) structured as an anthology purporting to cinematically bring these articles to life. Except that's oversimplifying: this is actually only true with the middle part, and even then I might've missed something, as the other two are presented as stories told about the articles, years after the fact, on top of already getting reprinted for the farewell issue, years after they were written. And so is added a further layer of complicating distance and commentary and age and memory (one of the episodes centers on an author with a perfect typographic memory, total recall of everything he ever read or wrote), which is, you know, right in line with my whole "Anderson at his Andersoniest" thesis.

Also, there is a prologue (after the preceding, expository introduction), called "The Cycling Reporter," which is short and punchy and necessary to situate us in this town/city/sprawling metropolis with its prisons and art collectors and universities and salaried police chefs and everything. "Ennui" is proffered to us by the Dispatch's local news reporter Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson), and nobody seems to think much of this one, yet it's my second-favorite vignette in the anthology. It sets the scene in a literal sense, but also sets the tone by letting you know how this film shall conduct itself, that is, mostly as a lightning-fast string of big jokes, small jokes, wry sub-jokes, blink-and-miss-it set decoration jokes, and mere attitudes and gestures that aren't jokes but I still found hilarious. (I spent The French Dispatch almost-but-not-quite laughing out loud at everything, and I only wasn't laughing out loud because there's something about the tenor of its humor that made it feel inappropriate to laugh out loud at it.) In any event, it's a fuguelike collection of visuals that, in their quick-cut aggregate, are splendidly funny in building the delicate and artificial world of Ennui, while also laying out the basic idea of the film: that it is best to use art to elevate our experience of reality, whether it's already beautiful, as is the case with, say, the bodies of Léa Seydoux or Timothée Chalamet, or whether it's not, as is the case with this storybook-styled shithole somewhere in Anderson's cartoon version of France, crawling with rats, cats, punks, and evil worms, given Anderson's customary treatment and turned into the cutesiest, glossiest versions of themselves. Everything's pretty, if you look at it right. Besides, Wilson's "Herbsaint Sazerac" (good grief) just tickles me.

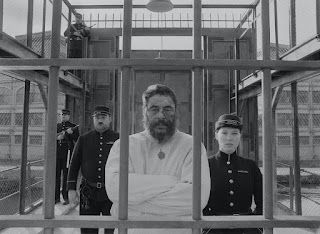

This gets us to the meat of the film. The first segment is "The Concrete Masterpiece," presented years later during a lecture by the "article's" author, J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton), and she tells us the story of the monumental artistic talent of Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro) that was discovered in prison by the not-quite-venal art broker Julien Cadazio (Adrien Brody) during the former's fifty-year sentence for a brutal double homicide, on the occasion of Rosenthaler's creation of his convention-breaking abstract nude portrait of one of his prison's guards, Simone (Seydoux), with whom Rosenthaler has fallen hopelessly in love; the second segment is "Revisions to a Manifesto," wherein Dispatch reporter Lucinda Kremetz (Frances McDormand) embeds herself amongst the student revolutionaries of a '68-or-thenabouts protest action at the local university, and winds up sacrificing her journalistic integrity to sleep with and critique the manifesto of one of the revolutionaries' leaders, such as they have them, Zeffirelli (Chalamet), providing the impetus for a dialectical synthesis between Zeffirelli's masculine pose and his feminine counterpart in Juliette (Lyna Khoudri); the third and final segment is "The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner," recited by Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright), holder of that typographic memory, during an interview on a tacky 70s talk show (and even the tacky 70s talk show looks gorgeous), and we loop through Wright's memories of one of his most exciting pieces of food criticism, when a visit to the Ennui gendarmie's head chef (Stephen Park) becomes a comic kidnapping thriller.

The biggest problem is that The French Dispatch frontloads its better material: "The Concrete Masterpiece" is, pretty much unanimously, considered the best the film has to offer. Both it and "The Private Dining Room" could be their own successful films, but "The Concrete Masterpiece" is the one that feels almost like it should be. But only almost: probably the reason it works so well is how condensed it is, coming off perilously close to actually being a feature-length Wes Anderson movie packed into half an hour. Also, like a good anthology short story, it has a twist, and this twist is, I think, the most effective emotional moment of the whole film, a character's frustrations evaporating into slack-jawed wonder over what he's helped make happen, at last able to enjoy something freed of any requirement to put a specific value on it. In this and in other respects, "Concrete Masterpiece" has the benefit of elucidating The French Dispatch's themes best of all them, but perhaps that's just the privilege of priority: it does what it does perfectly, and with inordinate verve, so that the subsequent pieces can feel very slightly redundant (though by the same token the repetition is part of the whole's effect). Anyway, since they're all about the same thing, and about them in much the same way, we can somewhat discuss the film's finer points without referencing this idea or that idea—this has somehow gotten very long with very few specifics—and just talk about how the whole thing is bound up in trying, as damned near as cinema is able, to communicate the splendor of art, both in terms of its creation and its appreciation. Hence the modal image of The French Dispatch being black-and-white (something its marketing campaign has taken pains to conceal), punctuated with disorienting images in color, almost exclusively the bright, poppy pastels that Anderson prefers, and usually coinciding with and meant to emphasize a character's contact with the sublime, whether that be an abstract nude, or Saiorse Ronan's eyes, or a lovely meal. It's jaundiced in a lot of ways—it permits you to have your own opinion as regards, for example, the usefulness of abstract nudes, or the ugly financialization of the fine arts—and it makes fun of the bullshit pompouness of art, a lot, including art Anderson obviously adores.

And that adoration, again, is communicated in ways that make me affectionate toward it even when I know I don't care about the inspiration—in terms of Anderson's specific touchstones here, Jacques Tati made one half of a masterpiece once, which is nice, whereas I'm sure my life, at least, is much too fucking short for Jean-Luc Godard—yet "Manifesto" does come closest to active antagonism, with its Maoist cringe comedy. The jokes can indeed be slightly cheap here, as "Manifesto" is also an open mockery of today's youth politics, which is one reason why it's the weakest segment, but I don't know, I also liked this about it. Maybe I was just in a mood for something so belligerently apolitical, cynical in its appreciation of how political belief becomes all the more of an aestheticized pose the more loudly "passionate" it gets. Anyway, maybe that's one way that, weaknesses and all, The French Dispatch couldn't be arranged in any other manner, with its final segment promising, "relax, fellow kids, I'm hip to the race question!", and in any case "Private Dining Room" isn't annoying, which "Manifesto" can be even when it's being satirical. "Private Dining Room," in fact, is modestly moving, grappling secondhand with the expatriate experience of pursuing a dream beyond the horizon, which (I'm guessing) that Anderson, a transplant Parisien himself, knows isn't actually there, and would only disappoint him if it were, which is why he's consoled himself all these years by imagining what could be there instead.

The French Dispatch is filled to overflowing with ideas about how to reimagine reality as something less disappointing, packed with so much interesting/cute artifice and impressionistic leaps through time that it's hard not to just start listing the gimmicks, like the way Tony Revolori, playing Moses Rosenthaler in his youth, is replaced onscreen by Del Toro and gives his older self a reassuring squeeze on his shoulder—but I'll refrain. It's an insanely busy motion picture as a result: one common observation about the film is that it's tiring, and maybe that's why "Concrete Masterpiece" is my favorite, and by the time "Private Dining Room" cued up, I felt overwhelmed, allowing it (more than anything else) to just be a showcase for the pleasant purr of Wright's voice counterpoised against Alexandre Desplat's metronymic score at its most anxiously rhythmic. But if it's tiring, it's tiring in the greatest possible way, a pretty little clockwork that eventually runs down. The film, in the end, is an old man's film, and I don't think he's faking it this time. It's a little nihilistic. But that's okay, too; what it seems to argue is that, eventually, brief, beautiful memories are all we have, so let's appreciate them while we can.

Score: 10/10

No comments:

Post a Comment