1998

Directed by Alan Cohn

Written by Anthony Abrams, Adam Larson Broder, Michael Traeger, and Mike White

"MTV Films," I daresay, conjures few memories, fond or otherwise, and while they're still a going concern (as a largely-meaningless imprint within the wider matrix of Viacom/Paramount's doomed attempt to secure what sectors of the market they can from Gog and Magog, that is, Disney and Warners), their shot at any particular historical relevancy or coherent identity was expended early on. Of their initial batch of films, pretty much all were bombs; the ones that weren't, were mostly movie editions of Viacom's animation programming, namely Beavis & Butthead Do America and, due to corporate synergizing, I guess, South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut. They struggled through a lot of failures with intermittent successes, and, leaving aside the persevering popularity of Jackass, at a certain point those successes began to stop looking like anything you might associate with MTV. My impression is that its corporate personality has never entirely died; I'm informed that their very latest direct-to-streaming effort, Three Months, still retains some of the hallmarks of an "MTV Film." But for a little while, there was something more like a mission and a style, or at least an approach: hip comedies for teens and young adults with the kind of edge that would make their parents quail. Yet the late 90s are separated from us by almost a quarter of a century and a cultural sea change, so what they are, now, are nostalgic comedies for middle-aged adults with the kind of edge that would make their kids quail.

Case in point, Dead Man On Campus, which is kind of the platonic ideal of "the film that couldn't be made today." Usually when we say that, we mean something actively vile, or at least fraught and uncomfy, as regards the two major avenues of offense, race and gender issues: a Blazing Saddles on the one hand (which probably could still be made today, but probably not by somebody who looks like Mel Brooks), or, on the other—and to keep it in the family of college comedies—a Revenge of the Nerds (which is, at best, a fantasy that isn't interested in comprehending "consent" even as the law would have been applied in 1984, and this is the charitable interpretation). Dead Man On Campus, however, is generally okay on these axes, or at least not overtly bad. (On sexuality, it's almost affirmatively good with the caveat "for 1998": despite a minor but film-long plot thread involving a case of mistaken sexual orientation, the only character to voice an even modestly homophobic sentiment is a despised antagonist.) In fact, it's "cleaner" on sex than virtually any of its near-contemporary genre-mates ("college comedy" and "high school comedy" becoming just different flavors of the same thing in the 90s, a conclusion especially hard to argue with when the casts of both are of the same average age, that is, around 25.) It predates American Pie by a year, which means it arrived too early to catch the wave of bro-horny 90s teen comedies, but I'd say it might be to its benefit; it's got a broadly similar attitude—sex! drugs! if we have time for it, rock and roll!—but one thing that will surprise you if you think about it is how, let's say, unbiological it is for a late 90s comedy. It's obviously not a complete read on an imprint that gave life to a Beavis & Butthead movie, but twenty years on, I find myself impressed with how, well, adult (maybe a better word is "judicious") the MTV comedies were, when the cornerstones are this, Election, Orange County, and Napoleon Dynamite. I mean, the alternative is, like, Eurotrip.

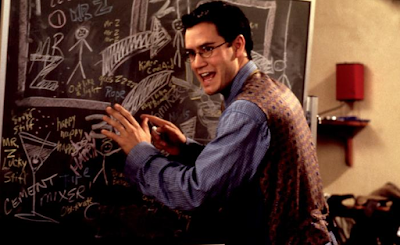

No, Dead Man On Campus's sin is utter glibness, and its sin is, in fact, doubled: not only is it glib about mental illness and suicide, it's glib about the entitled shitheads who'd exploit mental illness and suicide to get what they want. These shitheads number two, and though it's an even-keeled buddy comedy, the first one we meet and our plainly-intended point-of-view character is young Josh (Tom Everett Scott), an earnest lad who's arrived on scholarship at the University of Southern California's fancy Massachussetts branch campus, Daleman College, intent on pre-med. He has, as he will tell you, "a track." Enter Cooper (Mark-Paul Gosselaar, absolutely and with great relish channeling the idea of "Zack Morris at college," and in full Zack Morris Is Trash mode). Cooper's a fellow "freshman," of nebulous age and number of attempts, who's established himself magically as a figure of irreproachable popularity and suavity; he happens to be Josh's roommate. Though reluctant at first, Josh is soon seduced to Cooper's side—it helps that "poor study habits," "booze and pot," and "socializing with Josh's big crush and presumed deflowerer, Rachel (Poppy Montgomery)" go hand in hand—but midterms arrive and Josh might as well have not even shown up, whereupon he realizes that it's no longer even mathematically possible for him to get grades good enough to keep his scholarship. Cooper has his own moment of realization, brought home to him by his irate dad, who tells him this is the last time he's buying him into a school if he fails.

But that's when they find their premise: with a tip of the hat to the old urban legend, Josh and Cooper learn of an obscure rule in Daleman's charter that would award them straight A's should one of their roommates die of suicide. This seems of little applicability at first. Josh and Cooper alike nominate the other, for their friendship's sake, though neither seems especially keen on the idea. But between the absconsion of their third roommate Kyle (Jason Segel, unrecognizably young and neanderthalic), and the consequentially empty room, and Josh's work-study job in the housing office, and their diminished scruples, Josh and Cooper hatch a plan: find the most mentally unstable and at-risk guy on campus, reassign him to their dorm, and let nature take its grisly course, since, if it's going to happen anyway, they might as well reap the benefits.

Now, that is a premise. It's half-remarkable that a teen comedy even has a premise (a lot of them don't), and I can't name a single one that has this much of a structuring plot dependent on the step-by-step execution (so to speak) of a plan, so that the single biggest joke in the film is the one that never really gets stated aloud—the closest to acknowledging it is the couplet "We're really doing this"/"I know, we're so motivated," which like a lot of things, is funny thanks to Gosselaar's read—and that's that Josh and Cooper's plan is easily more work than it would have taken to just get good grades in the first place. The other thing is that it is so deliriously ghoulish, and while there's much to love about Dead Man On Campus, this is what makes it so appallingly, appealingly dangerous. It has no real legacy, but this is the Internet, so you do not, obviously, need to look terribly far to find someone spitting on it, apparently out of a categorical rejection of the concept of "dark comedy"; but it underperformed badly and was widely disliked in 1998, too. I don't really quite get why. Election has its scolds, but is considered canonical. Is this more tasteless? There's no arguing with the subjectivity of humor, but it's not less funny. It is probably simply that Election is very loudly About Things and Dead Man On Campus is about itself, which is one way it's the better movie; and I'm very happy to call it the last truly great college comedy. That is, to the extent such things have ever existed, anyhow.

That premise is pursued with a gleefully irresponsible diligence (the first step is breaking into the school's confidential psych records), and leads into a terrific second act, though even before this Dead Man On Campus has been doing basically everything right. The ambling, plotless first act that should be all set-up for the premise is tremendously fun even before the movie properly "starts," capturing a time-capsule fantasy of "college" in 1998. Why, it even winds up threatening to be about something after all, in its critique of saddling overachievers with overwork (and professors who force you to buy their overpriced books), though much like Cooper's penchant for buttoning his garments in presumptively-fashionable yet seemingly-arbitrary ways, the notion of "college students burdened with more than five hours of work per week, including class attendance" is, perhaps, something you only see in old movies. Anyway, that fantasized version of college is best summed up in Josh's dazed monologue, "It was so easy... It was just like, 'Time for sex. We're gonna have sex. Prepare for sex.'" But the joy of all this new discovery on Scott's goofy crinkly face makes me laugh and smile, even though my own college experience put me closer to the ideal candidate for Josh and Cooper's spare bedroom, which may be why I respond so positively to a movie that seems to viscerally turn everyone else off: it's not about the profound dislocation a young, depressed, and frankly suicidal boy can feel when he's tossed into an alienating situation that isn't remotely "easy" for him, but it's not about that so conspicuously that it sort of suffuses the whole movie after all, a twisted Kafkaesque version of higher education where it turns out I was right—college actually does want you die. (And not to spoil anything, but when they do arrive upon a genuine "perfect candidate," he was right under their noses and had gone unnoticed all along.)

But that's enough spent on what it's not about: what it is about is a vignettish "second act" that parades a series of parodies of various stripes of "mental illness" up and down the film. (It's not a problem, but it's actually more like a movie with one long first act and four short subsequent acts. It's weird, but feels totally correct.) In turn, Josh and Cooper are confronted with their possible victims: Cliff O'Malley (Lochlyn Monroe, and as the closest this underseen film gets to an "iconic" character, I feel that the full name is a requisite), a fratboy addicted to adrenaline and, possibly, crack; Buckley (Randy Pearlstein), a paranoid conspiracy theorist who believes, well ahead of his time, that Bill Gates is attempting to infiltrate his brain (his last line is "I'll be back!" which proved to be depressingly prophetic); and Matt (Corey Page), frontman for a parody of a Smithian rock band, making him the Morrissey, whose whole brand is performative suicidal depression, and is therefore the only character that the film actually hates. And these are all spectacularly good comic characters, shuffled through quickly so that the film's frequency never goes stale (and it's notable that the writers were sensitive enough, or at least smart enough, not to zero in on any "mental illness" with a sympathetic real-world analogue, though it's fair to nitpick Josh and Cooper's initial scheme to ride Cliff's self-destructive streak to academic rewards, as even under a liberal interpretation of its text, I'm pretty sure the rule demands "suicide" and not "death by misadventure," let alone "death in a gunfight with the police during commission of multiple felonies").

It's pretty fantastic, plumbing depths of comedic fear at what they've unleashed with Cliff, and comedic cruelty with their awful enablement of Buckley, and comedic contempt with Matt; and Dead Man On Campus has the good fortune to be driven by actors who are unflaggingly vigorous in pursuing their cartoonish stereotypes. Every one's given their opportunities to shine; Cliff's favored with the most, because the filmmakers obviously fell in love with the insane id monster Monroe created, so much so that they had two separate "CLIFF'S BACK!" endings that conclude with someone screaming in horror, and they used both, saving one for the post-credits sting.

But most important of all are Scott and Gosselaar, holding the center. They're perfect scene partners, bending toward each other and encouraging each other's toxicity in ways that effortlessly convey why these opposites are friends, while continually responding to each other's energy (smarmy big man on campus vs. the sincere, hard-working dork he's corrupted) with a surfeit of all-time great bickering. Thanks to them, the script winds up being almost front-to-back funny, nearly devoid of misses entirely—which is astonishing, considering that every other line is, to some degree, trying to be funny—but varied in the ways it accomplishes this. The baseline is always Scott and Gosselaar's deadpanning (a cute trick of the script is how they alternate the sarcastic "straight man" role throughout, when they're not both playing straight man to the maniacs), but this is punctuated by strong physical gags (even two whole sequences that I'd say rise to the level of "actual setpiece"); there's a lot of archetypal "90s comedy" ("the existence of marijuana" gets a lot of play), but there's also a penchant for putting intentionally creaky buttons on scenes that suggest that Scott, Gosselaar, and director Alan Cohn were equally as fond of archaic vaudeville-inspired sitcoms and actual cartoons.

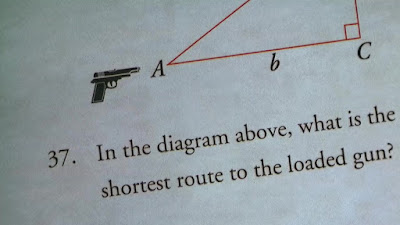

Plus—and this is what, I think, puts it in the top-rank of just "all comedies, generally," let alone "teen comedies"—it has actual aesthetic concerns. (Cf. Orange County, which is a great movie and I don't think often rises above the level of "perfectly fine to look at.") I'm tempted to attribute an unusual emphasis on visual storytelling to its producer, the great Gale Anne Hurd, but that would be entirely speculative. So that means all credit goes to Cohn, who regrettably never did a feature before or after this one (he did one TV movie, Spring Break Lawyer, which is the kind of title that I'd say sums up the whole era's comedic sensibility), or, rather, to Cohn and editor Debra Chiate. There's not much to actively dislike about cinematographer John Thomas's work: there's a genial comedy sunniness that I will never not like in a movie, even if it's muted in comparison to its 80s counterparts, and there are occasional efforts to use shadows interestingly, and the institutional blandness of college is, in a way, an aesthetic of its own (to get slightly critical, Thomas has a mild problem with using too much shallow focus, but this is genuinely almost unnoticeable). But Dead Man On Campus winds up with a terrifically strong visual identity anyway, starting with its very first gesture, an opening titles sequence on the theme of test booklets turned towards the subject of suicide, courtesy designer Karin Fong. It's one of the best (and almost undoubtedly the funniest) iteration of its type of opening credits montages ever made; it's a pretty good sign, if the opening credits make you laugh out loud. (You might expect more from a Mark Mothersbauch score, but it's fine, and either way, the sonic heavy-lifting is mostly done by the soundtrack, befitting an MTV film, though besides Squirrel Nut Zippers' "Hell"—natch—it feels usefully obscure.)

Cohn, in any case, is pretty stubborn in his refusal to take easy outs and never lazily just "makes a comedy." (There are individual exchanges that fall to that level—there's a shot/reverse-shot dialogue with Josh and Cooper where "why bother?" and "shallow focus" combine for very deflating results—but these are brief enough to not count them, and just figuring out ways to make conversations in realistically-cramped dorm rooms interesting is an accomplishment.) The most noticeable flourishes are in the first act—the film never commits as hard to subjectivity or experimentation as a splendid montage that bleeds Josh's inebriated pleasure-seeking and his scholastic obligations together, and puts Scott and the camera on a rotating platform so his head floats happily through space—but all throughout, there's a sense of really excellent timing, and a careful shepherding of visual information, that enhances every punchline, and frequently enough serves as a punchline in its own right. And that would be good already, but with that malignant dark comedy premise, it's great; and with an ending that brilliantly manages to have its cake and eat it too (it somehow winds up heartwarming and completely repulsive simultaneously, resolving the tension but confirming the cheerful cynicism, too), it's a masterwork of edgy comedy that somehow got edgier as the years went by.

Score: 10/10

No comments:

Post a Comment