Friday, September 11, 2015

The matador

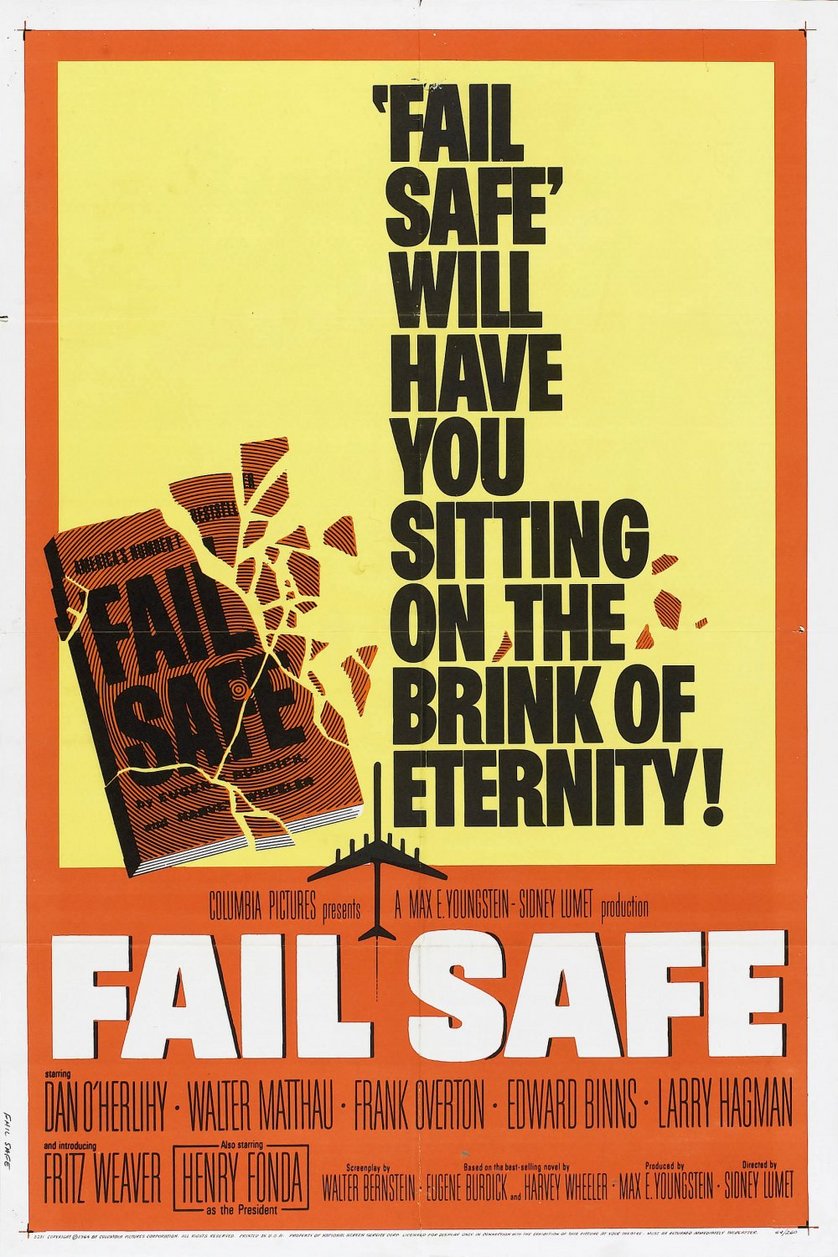

FAIL-SAFE

The best Cold War movie of 1964—and that's saying one whole hell of an awful lot.

1964

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Written by Walter Bernstein and Peter George (based on the novel by Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler)

With Henry Fonda (the President), Larry Hagman (Buck), Walter Matthau (Prof. Groeteschele), William Hansen (Sec. of Def. Swenson), Frank Overton (Gen. Bogan), Fritz Weaver (Col. Cascio), and Dan O'Herlihy (Gen. Warren "Blacky" Black)

Spoiler alert: moderate, although presumably someone made you watch this in high school

In 1964, the movies lost faith in the military-industrial complex. This had been a long time coming: once both sides of the Cold War had nuclear arsenals, H-bomb paranoia had become an international obsession—and filmmakers naturally seized upon the cinematic possibilities. Movies like Five, On the Beach, and The Time Machine dealt with nuclear war in the abstract, assuming that should nations ever do battle with nuclear arms, everyone would lose. Yet these were cautionary tales, and there remained a certain belief that we could depend upon our deterrent to do exactly what it says on the tin: stop nuclear war from ever starting in the first place. We could stake our lives upon that system, and this was good, since we didn't really have a choice. But then came Sputnik; next, the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was the closest we ever came to nuclear war, and that un-American idea—that the people in charge actually knew what they were doing—received its fatal blow.

It didn't help when theorists like Robert McNamara and Herman Kahn publicly retreated from the Eisenhower administration's cartoon version of nuclear warfare, "massive retaliation," for more nuanced policies, priding themselves on thinking about the unthinkable. But by applying reason to the unreasonable, they made nuclear war frighteningly conceivable. By suggesting that it could be controlled—even that it could be made a certain value of winnable—they seemed to make it more likely. The substance of our bloodless strategists' ideas was all but ignored; the public only saw more missiles, bigger bombs, and a looming apocalypse. And so a fatalistic era had begun, where the end of human civilization seemed inevitable, and science heroes could not save us.

By 1964, cinema had digested the modern terror. Over the course of twelve months, American filmgoers were subjected to failure after failure of the system they had grown to distrust. First: Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove, the blackest comedy ever made, twisting every aspect of the Cold War toward bleak slapstick, finding absurdity in its horrifyingly accurate central conceit—the possibility that a madman could start World War III, all by himself.

Next: Frankenheimer's Seven Days in May, and perhaps its humorless satire was more subversive still, supposing that the U.S. military was so enamored of their nuclear bombs that they would kill a president who took them away. Seven Days differs from Strangelove in that it doesn't imagine a madman is required to promote nuclear war—the sane can arrive at the same conclusion.

Finally, trailing the pack: Lumet's Fail-Safe. (Often rendered Fail Safe, without the hyphen; but I shall direct you, dummy, to the title card.). And in Fail-Safe, nuclear war happens through no human agency at all—by pure, awful accident—suggesting with the bitterest possible fatalism we'd already doomed ourselves years ago.

In production at the same time as Strangelove, Fail-Safe was so similar in its broad outline that Kubrick sued, initially demanding that the film be shelved. The producers' out-of-court settlement resulted in Columbia distributing both pictures—and releasing Kubrick's comedy first. That's a little unfortunate—because despite such nearly identical plots, very few movies could be more different in their execution. Fail-Safe is Strangelove done straight, nearly the Airport to its Airplane! We can therefore sympathize with audiences who saw both, and couldn't take the thriller seriously while visions of the farce still played behind their eyes. That doesn't mean we have to condone those jaded reactions: 51 years after the fact, we can recognize that each film is altogether perfect in its own precious way. Yet I contend that we should avail ourselves of the opportunity that time has afforded us: both must be seen; and Fail-Safe must be seen first. (While Hank Fonda, incidentally, agrees.)

I didn't have that opportunity myself—but even then, I prefer Fail-Safe by a hair. Maybe it's mere overexposure: having seen Strangelove about twenty times, and Fail-Safe only three—and just once in the past ten years!—Fail-Safe probably can't help but seem like the fresher take. But it's awfully hard to dismiss Fail-Safe's sheer intensity, particularly when set against Strangelove's prankster attitude—even given that Strangelove is itself a uniquely intense comedy. If Fail-Safe must be regarded today as an enjoyable "what-if?"—you'll notice WW3 did not actually occur—it raises that question so brutally that you'll be quaking afterward. Fail-Safe, of course, is a story about a nuclear war—happening right here and right now—and about our fumbling attempts to end it.

At SAC headquarters, an alert is triggered on the big board: a UFO is spotted, and the system springs into action. Bombers drive toward their fail-safe points, prepared to attack. With a congressman on hand to witness the efficiency of our defense establishment, everyone is in a particularly self-congratulatory mood when the UFO turns out to be an airliner, and the bombers are all recalled. Unfortunately, smugness shades into tightly-controlled panic when—in a seemingly impossible contingency—it is realized that two vital pieces of their sophisticated system have malfunctioned simultaneously. One group of bombers has sailed through its point of no recall. Infinitely worse, the machine has transmitted to those bombers an authentic order to strike. The fail-safe has failed.

As the global holocaust commences, we are invited partway into the lives of our cast: the stolid General Bogan, in charge at SAC HQ; his less-than-balanced subordinate, Colonel Cascio, whom we meet at his parents' house under awkwardly unpleasant circumstances; Professor Groeteschele, an edgily square nuclear theorist patterned on McNamara and Kahn, whom we meet at a party, discussing the relative virtues of a nuclear war that kills 100 million compared to one that kills only 60; and the pacifistic General Black, whom we first encounter in the hallucinatory nightmare that opens the film—the matador who slays the bull. Black will carry Fail-Safe's most unshoulderable burden; but the film's protagonist appears much later, at exactly 41 minutes into the film, because that's exactly how long it takes this buck to stop. (Let's pray that the character Buck—the President's interpreter—had his name arrived at through a coincidence.)

The film now becomes the story of America's nameless President as he assumes his gravest responsibility. From this point, Fail-Safe operates almost as a stately procedural, but an unbearably tense one. Ultimately, the President must make contact with his counterpart in Moscow. But that decision is not unanimous, nor taken easily. Groeteschele insists that our only option is to commit ourselves to this preemptive strike, rather than blithely accept Soviet retaliation. Others are less coolly rational, more violent—revolting at the prospect of helping Russians kill Americans. Finally, a last desperate notion is conceived, straight out of the Old Testament—so barbarically simple that it hardly merits being called a "plan." In the end, the cost of our folly is so unimaginable that the nastiest thing any director could ever do is to make us imagine it. This, of course, is exactly what Sidney Lumet does.

Given the more sedate manner of his later career, it's easy to forget that in his early days, Lumet was one hell of a stylist, particularly in the editing room. Above all, there's The Pawnbroker, arriving earlier in 1964, whose fractured, vicious cutting between contemporary NYC and wartime Auschwitz is its chiefest point of recommendation. Later, the climax of 1971's The Anderson Tapes will threaten to destroy spacetime itself. Even 1957's 12 Angry Men, regarded far more for its script than its visualization, is enormously stylized, with its portentous close-ups, crushing low-angle camerawork, and blocking so exact that it finally crosses the line into strange patriotic ritual.

Fail-Safe fits squarely into this early, confrontational style, and the basic elements of Gerald Hirschfeld's cinematography have already built the foundation for Fail-Safe's dour thrills, even before we get to Lumet's more specific choices. Fail-Safe's war is waged in grisly high-contrast black and white, and its subjects are bathed in shadows—the angle of the light growing ever more acute and vertical as the film progresses, not unlike the intolerable light of a nuclear fireball—while the actors' faces emerge from an oppressive layer of nearly-pointillistic grain.

And such faces they are: Fonda leads the cast, of course; but indispensable to his effectiveness is his uncanny screen partnership with Larry Hagman. As the President's interpreter, Hagman occupies Fail-Safe's trickiest role. At once, he must be the subservient tool of the president, a stand-in for the Soviet premier for whom he translates, and a human in his own right. (His silent reactions in this third capacity are nearly as invaluable to Fail-Safe as the face he gives the Soviets.) Meanwhile, Walter Matthau gives his un-nutty professor surprising depths; an early scene witnesses his crotch getting jumped by a nubile nihilist. Rather than availing himself of the planet's only nuclear pundit groupie, Groeteschele violently demurs, "I'm not your kind." But we really have to wonder. As reality sinks in, however, and he begins to ramble on about rescuing economically important documents from the rubble of cities, Matthau's performance confirms that what he said was true. All Groeteschele's theory—his sophistry, if you must—was only that basic human impulse, to sterilize the unpleasant chaos of the world and try to make it orderly, if only in the mind.

Beneath these three sublime performances are the merely perfect ones. But Lumet was always an unparalleled director of actors.

Now let's add back in his mastery of image—those enfeebling shots of the leader of the free world, made subject to a monstrous telephone—and, more crucially still, his mastery of montage—those quick cutaways that refuse to accord with the beginning or end of dialogue, jumping right up and down on your nerves, contrasted with those long, simmering takes while decisions are implemented. It's cinematic brutalism from start to finish, from the punch in the nose of its title-card till the closing credits. It is straightforwardly cruel—devoid even of the flourish of a score. (Whereas the techniques we have discussed are scarcely pretty enough to be rightly described as "flourish.")

In terms of scope, Fail-Safe is easily its director's biggest film—it deals with the fate of the race, when Lumet's perennial focus was upon the fate of the invisible men on the corner of a city block. But even 12 Angry Men and Dog Day Afternoon, virtually confined to single rooms, never feel this claustrophobic. Fail-Safe was cheap, and its cheapness works, enforcing a cramped minimalism upon its designers. The entire aesthetic is bent toward the impression of constraint: constraint upon movement; constraint upon action. The President sits in his tiny, hot room beneath the Earth. (Lumet's best films all seem to involve Henry Fonda trapped in a tiny, hot room.) He commands through a vast, unknownable instrumentality, which we see only glimpses of—indicator lights, men at workstations, the big board. World War III shall be fought with electrons. It is unbelievable how much suspense Lumet can create with nothing but animations upon a rear projection screen.

That's the broader target of Fail-Safe's pique—humanity's creation of great systems, so large and complex and fast that human hands cannot control them. The President mourns the day we ceded our shared destinies to machines—and to procedures that render men into machines. These bomber crews don't think, only execute. (And as we recover from the implosion of a grand system built without any fail-safe at all, this idea is as relevant as ever.)

Surely, Lumet and his screenwriters mince no words: Fail-Safe is frankly propaganda, taking on the most important problem in the world with passionate anger and definite bias. Today, that's difficult to recognize, because its ideas were too successful: any discussion of nuclear war more complex than "millions die for no reason" became virtually a forbidden subject. (Yet it's surprising how respectfully Lumet treats the opposition. The result is that Fail-Safe, despite the liberties taken, winds up perhaps the most literate film about nuclear war ever made.)

But if it's propaganda, that's no criticism: it joins the ranks of Strangelove, Soylent Green, and Lumet's own 12 Angry Men as a cinematic polemic that actually has changed the world for the better—and entertained us in the process, though Fail-Safe's "entertainment" is truly of the queasiest, most unsettling kind there is.

Score: 10/10

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

You're basically my only source for classic movie love. I may not have seen any of them, but I know everything about them now. Speaking of: Are you free enough to do our crossover again this October? I've got some great titles planned.

ReplyDeleteHell yeah, I am.

DeleteAlso, it's sweet of you not to suggest that all those movies you watch made in the 1980s--that is, within my lifetime--haven't already graduated to Old. But we both know the truth!