1941

Directed by Clarence Brown

Written by Virginia Van Upp and Patterson McNutt

As of 1941, Clarence Brown had spent more than a decade, with only occasional breaks for anything else, pursuing a very particular kind of women's picture, frequently with Greta Garbo and only slightly less frequently with Joan Crawford, that combined some of the most overt sexual moralizing you'll ever see even in a 30s movie with an almost instinctual sympathy for the misunderstood women at the center of them. He managed perfection right out the gate with this, reconciling Garbo to her star in 1927's Flesh and the Devil (like I said, the moralizing is overt even for Hollywood). I'm not sure he ever did better than that film, though certainly Brown acquitted himself well across the next decade, even producing at the end of the 30s, and thereby putting the seal on this phase of his career, 1939's The Rains Came, which is also either a masterpiece or very near to one, and either Myrna Loy's best performance or very near to that, too. With something like fifteen sexual morality plays (sometimes you'd still call them "romances") under his belt, he started to stretch somewhat in the 30s, indulging in comedies like 1936's Wife vs. Secretary (also with Loy, also extremely good), and eventually he found a whole new niche for himself in the 1940s, as—essentially—MGM's Frank Capra. He'd experimented (or, as a contract director, been assigned to experiment) with this mode as early as 1935, even before "Capra-corn" itself existed, with Ah, Wilderness!, which is unfortunately pretty awful; and Brown began the 40s with what's said to be one egregiously hagiographic treatment of Thomas Edison.

In 1941, the currents of Brown's mid-career collided in a romantic comedy called Come Live With Me, named after a line in a Marlowe poem which is recited, to the extent the character reciting it can remember it, at a key moment in the film; it also applies to more than just the narrative-driving farce, since to get to that narrative-driving farce, Come Live With Me replicates (really, prefigures) a trick from Hold Back the Dawn, centering itself upon another imperiled emigrant lately come to American shores, and in this instance having actually gotten here before the movie's begun, but overstayed her visa some months earlier. This emigrant is Johanna Jans—Anglicized, curiously, to "Johnny Jones"—and in case you were wondering, the film does indeed come startlingly close to simply explicitly describing her as a victim of what was already being referred to as the Shoah: her father has been liquidated ("oh, murdered, like we say it over here"), for fuzzily-specified reasons, by the authorities in ("what used to be") Austria. An assumption you could readily make is that she's as Jewish, at least under the Nuremburg Laws, as her performer would have been, this being Austrian expatriate, actor, and military engineer (no, really, look it up) Hedy Lamarr.

But we don't meet Johnny immediately. Instead, we begin with one Barton Kendrick (Ian Hunter), a middle-aged (but don't tell him) book publisher, evidently a man of sophistication and means, presently saying an enthusiastic farewell to his wife Diana (Verree Teasdale) and failing to do much to reassure her about her own age-related insecurities, despite the fact that she's going on a date with a man who is, to all appearances, her boyfriend (Edward Staffley). Well, Bart has his own date to keep, after all, with his own young paramour, and that's none other than our Johnny, stashed away in her own apartment (for she has, at least, managed to extricate her inheritance from Europe), eagerly awaiting their appointment. Unfortunately, into the midst of this would-be clutch comes an immigration officer (Barton MacLane), and, sympathetic to her plight, he lets it slip, nodding in Bart's direction, that if she were married to an American citizen she'd hardly be deported then. Leaving her with her freedom, he gives Johnny a week to sort it out, entrusting her compliance to her word.

This is political, but Come Live With Me has said what it has to say directly on this topic, and the danger of Johnny being shipped back to Nazi Germany never comes up again after the film's first fifteen or so minutes. But right away we see the film combine the indulgent smile of its adultery comedy, straddling a line between sincere feeling and the overwrought silliness of Bart's ride out to Johnny's place prefaced with his hilariously-useless exercise routine on a mechanical horse (and therefore scored with with a very ironic "The William Tell Overture"), with the American self-image of an immigration cop so foundationally gosh-darn decent that he actually uses the honor system with deportees. Thus are we invited to get a handle on what this strange little movie's going to feel like, which is, somehow, a hybrid of Capra with Ernst Lubitsch, two names rarely associated with one another unless someone's just listing "directors from the 1930s." It doesn't hurt that Capra connection, anyway, that on Johnny's lonely, dejected walk as she tries to figure out what to do with her newfound lifeline to America when the only man she'd like to wed is already married to someone else, she runs across a bum so broke he's pitied by other bums, and this bum is Mr. Smith, literally Mr. Smith—Bill Smith—and he's played by Jimmy Stewart. And when I say it's like a hybrid of Lubitsch and Capra it's more like they've been smooshed together, an elegant and fancy continental who's found a place with an elegant and fancy American, slammed into a bumpkin who's foolishly come to town to make his fortune (Bill is a writer) and failed so completely that not only can't he afford food, he can't afford cigarettes, so that's why when he meet him he's scrounging butts off the pavement. (It's rather more brass-tacked about the Great Depression than you usually get from a movie as late as 1941, too, which is another way it resembles a 30s Capra holdover. Less Mr. Smith than Mr. Deeds, really, though it's Mr. Deeds but poor.)

But you can probably see where that goes: after an antagonistic meet-cute, Johnny accompanies Bill back to his extremely humble home, and, slapping him when he attempts a kiss so he makes no mistake where he stands, asks him to marry her. Reluctantly and with huffing officiousness (and tabulating his living expenses as conservatively as possible in a failed bid to retain some dignity), Bill agrees. And she agrees to visit once a week to deliver his check. (She decides it best not to tell him where she lives, and she's probably right.) But in the meantime, Bill manages a draft of his first salable novel—the story of a refugee and an everyman whose fake marriage blossoms into love—and finally gets his break. The break, of course, arrives by way of Diana Kendrick. She thinks it's really good if he'd just pin a happy ending to it; she also figures out within seconds of showing it to her sputtering husband that this is no fiction. The even worse news for poor Bart is that Bill has gotten it into his head that he does love Johnny, and is prepared to go to some lengths to convince his bride to stay, though he's slower on the uptake than Diana, not yet realizing that his would-be publisher is his rival for Johnny's affections.

That's a lot of plot for an 86 minute film and it's not even over, and while the signal strength of Old Hollywood was always its commitment to responsible runtimes, this time you feel like whole chunks are just getting left out. We do not, for starters, see Bill and Johnny get married; we do not see Johnny deal with her immigration status; in fact, for a lot of the middle act, Johnny's in the movie less than you'd think the co-lead of a romcom, introduced as the protagonist, would be; we also never see Diana's own paramour again, after his one scene. You can chalk this up to just being efficient, but this is crazy efficient, even counter-productively efficient, and while Brown (or scenarist Virginia Van Upp, or screenwriter Patterson McNutt) find ample room for enchanting comic business—not infrequently coupled with actual character work—I'm not sure there's really a reason that Bill decides to go ahead and fall in love with Johnny, except that Johnny is Hedy Lamarr and you'd have to be blind not to. (Accordingly, there's some untapped potential in the subtext that Johnny's just fallen in love with the fictional character he based on Johnny, albeit so untapped that to even describe that as a "subtext" is already forcing it.) I'm not sure why Johnny falls in love with Bill, either, except Stewart is Americana incarnate, and that's what this movie's about. But whatever it is, Lamarr and Stewart's performances are doing an unusual amount of work even for a romcom from the 40s, the former with the brute fact of her otherworldly beauty, enhanced by Adrian Greenburg gowns, and the straightforward, unadorned integrity she brings to her Johnny, the latter with his handsomeness, muttery comedy, and lanky, aw-shucks charm.

Stewart gets the better of it, then, and for an MGM romantic comedy that seems to have no desire for even touching actual "drama," Brown encourages all the actor's more interesting instincts, almost-but-not-quite to the point of Stewart being distracting and "too good" for the froth of the material: Stewart was always most fascinating when there was a little darkness to him, in precarious balance against his better angels (his Hitchcock movies in the late 40s through the 50s lean into this, but Hitchcock didn't "discover" this subverted side to Stewart's persona; it was around since the beginning, hardly more evident in Rope or Vertigo than in Ice Follies of 1939, let alone After the Thin Man).

Stewart certainly has a bit of dark to work with here, bubbling with resentment and prone to acidic social commentary, and occasionally coming off as an out-and-out lunatic. This isn't always entirely successful: McNutt's script tries very hard to navigate the smash-up of Lubitsch Mode and Capra Mode that transplants the action from New York City to a bucolic plot of farmland upstate—complete with a cozy (but luxurious) home, festooned with aphoristic cross-stiches produced by its inhabitant, wise Grandma Smith (Adeline De Walt Reynolds, somehow in her film debut, inaugurating a career that would only conclude fifteen years hence in The Ten Commandments), and which is so Capraesque that it even puts a partition between its romantic leads slightly reminiscent of It Happened One Night, a Capra movie that isn't even that Capraesque itself—but neither the screenplay nor Brown's direction nor Stewart's emotional gear-shifting completely mutes the shuddery clunk of this impact, so you retain the distinct feeling that the film needed at least a few more minutes, so this turn seemed more persuade-y and less, well, kidnap-y. Fun verbal play does help. It's been a strong element all along (Bill must've been written for Stewart, and even so Stewart feels like he's using McNutt's script more as a guideline); but either way the explanation, "You might as well cooperate, or you're just holding up your own divorce," is very funny in the read, and at least sets a solid baseline "definitely not going to murder her" vibe, which is sometimes all you can ask of the male lead even in great 40s romcoms (for example, Princess O'Rourke doesn't uniformly pass this test).

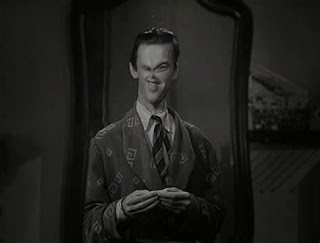

And one does need such assurances, since Bill is a weird guy, emphasized by his penchant for talking into mirrors, though this is a more successful gesture—even at its most violent. For all its questionable mores, it's a terrifically nice movie, and as much as overt niceness was the direction Brown was moving in, empathy was always one of the sharper tools in his set, and even his cruelest films possessed that. This one is heartbreakingly kind to its adulterous older spouses—amidst this tottering open marriage, that feels like it was lifted out of a pre-Code film and plopped into an MGM picture from 1941, Teasdale gets a long close-up to deliver a sensitive monologue outlining Diana's feelings for her straying husband, where she explains that she'll give him the divorce he wants but only if he actually needs it; I'm happy to report she made me tear up a little. It wasn't the last time I would, and while I've been content to talk about Lubitsch Modes and Capra Modes, I didn't intend to imply there's no such thing as a Clarence Brown Mode. There absolutely is, partly just in how his film was manufactured, from the perfectly-timed camera move that introduces Lamarr shrouded in glamor, to the willingness to put Stewart's face in unflattering shadow to emphasize his mean streak, to the light psychological horror-comedy he gets up to with mirrors, to the use of darkness and bursts of light as signifiers of burgeoning love, no less effective here, and maybe more effective, than the first time he used it, with Garbo and Gilbert back in Flesh and the Devil. One use of light is supremely effective in the corniest way: I am really impressed by the matchlight that illuminates Grandma's cross-stitched sign in Bill's bedroom, stating "If at first you don't succeed, try, try again," showing it to us, whilst Bill remains oblivious.

The entire finale is corny—and there is barely adequate buffer between the set-up involving the spectacle of fireflies, and the denouement that pays this off, and once again this 86 minute movie really needed to be even just 90—yet it is all so gorgeously corny. It's almost bizarre, but more enjoyable for it, to watch something that's had its moments of real emotional and sociological insight (I mean, in a bitter read that probably barely skirted the Production Code, Bill almost explicitly compares himself to a prostitute), yet systematically dispenses with such things. It leaves realism behind, judging it completely unimportant and, indeed, unwanted, in the face of its fiat romance, its heap of agrarian sentimentality, its beautiful silent storytelling, and even a final frame that assaultively breaks the fourth wall for a dorky-as-hell, hot-as-anything kissing gag. It's as perfect an exemplar of pure Old Hollywood artifice, even specifically Old MGM artifice, as you could find. It's phony, you know it's phony, it's almost obnoxiously phony—and you realize it doesn't matter anyway.

Score: 9/10

No comments:

Post a Comment