2004

Directed by Zhang Yimou

Written by Li Feng, Peter Wu, Wang Bin, and Zhang Yimou

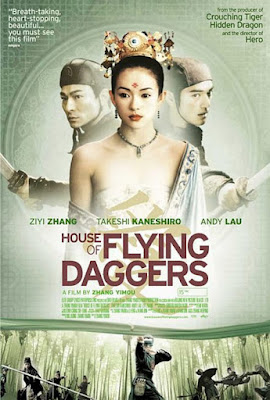

House of Flying Daggers blipped into American theaters in December 2004, only three months after Hero had finally made its way to the States and done (for a foreign-language film) comparatively boffo business, and while there's no shame in a $12 million American run for any Chinese-language film, it's a pity that it was not more successful. Speaking personally, it's my very favorite of Zhang Yimou's wuxia films, since it's somehow even more playful than Hero in its visual imagination, while also delivering a far more overwhelming story. (I have not, at the time of this writing, seen The Great Wall, but I suspect it's okay to stick with superlatives.) In a way, however, Daggers is just Hero's B-side, almost a container for the leftover ideas. This is true aesthetically and narratively, and it's not too much to say that it's an elaboration on Hero's secondary themes, so much so that I honestly wonder if Zhang consciously designed it as such: Daggers, which doesn't have to deal with the founding mythology of China, basically takes the other, smaller part of Hero, the violent romantic tragedy of Broken Sword and Flying Snow, and expands that to fill its own entire movie. It redeploys one of Hero's stars, too, promoting Zhang Ziyi from supporting role to lead.

It thus arrives as maybe the single most elemental of Zhang's films, almost exclusively concerned with love, sex, lies, and possessive jealousy, and to the extent Zhang's usual sociopolitical hang-ups enter the picture—and they do, since if Hero is nakedly about the foundation of the Chinese nation, Daggers might be an allegory for the foundation of modern China—they're still only a backdrop for the more primordial problems, so much so that the film seems almost disgusted with how secondary and meaningless a civil war winds up, in comparison to all the love, sex, and so on that it would rather be about. The politics are just how the good things in life are denied to its heroes if they hesitate to free themselves, and, as it's a Zhang Yimou film, you can kind of guess they hesitate at least one moment too long, and that's where the "tragic" part comes in. I adore it completely, even if it's not perfect. It's less "perfect" than Hero already was: it's demonstrably sloppy in its plotting, and that's hard to overlook (one thing that it makes a hugely big show out of I have to assume must be some kind of hazy metaphor, because it sure as hell doesn't matter much to the plot). Yet it's intelligent in its simplicity anyway. I said it's my favorite Zhang wuxia film, sure, that's not too controversial, because no one cares what your favorite Zhang wuxia film is. But it's ultimately my favorite Zhang film of any genre, including Raise the Red Lantern, which is undoubtedly blasphemous, though if you're surprised that I like the movie with the swordfights and the raw passions better than the mannered slow-burn amongst sex slaves, then apparently this is the first time we've met, or maybe you're just surprised that somebody who can string two polysyllabic words together about any movie might slightly prefer this one.

So, in its historical fantasia, Daggers takes us to the waning years of the Tang Dynasty. It has less than half a century to go before it finally collapses, and numerous rebel groups have risen to challenge the state, most prominently for our purposes the (fictional) "House of Flying Daggers," a fitting name given their weapon of choice. (They also have at least two houses, but this is figurative.) Recently, their leader was successfully assassinated by the Tang authorities, but even this has done little to slow them down. Text explains that they operate in secret, not unlike a certain gang of Sherwood radicals—not to put too fine a point on it, not unlike out-and-out Maoists—and, accordingly, they've gained the support of the population by robbing from the rich to give to the poor, which makes them the "good guys."

Naturally, then, our hero must be one of the bad guys, the Tang government's sheriff, and that's Jin (Takeshi Kaneshiro), and we meet Jin as he's tasked by his commander, Leo (Andy Lau), to go undercover to the new brothel in town in pursuit of a tip that they're harboring one of the Flying Daggers' female members. Swaggering into the place, Jin is captivated by the beauty of the brothel's most recent acquisition, who bears the unadorned name of Mei (Zhang Z.). Mei is also blind. In a very curious coincidence, so was the daughter of the Flying Daggers' slain leader. Thus do Jin and Leo identify their quarry and set a trap. Jin makes an outsized ass of himself, feigning an attempted rape of Mei—just to get it out there, this is a rapier film than some may enjoy (it gives another, realer rapist human feelings, but also makes him the antagonist, so the next time the issue comes up, it's treated with a lot more gravity because it isn't pretend)—and, as planned, Leo shows up to arrest both of them for breaching the peace. Cornered, Mei volunteers that she is indeed a Flying Dagger, and tries to kill Leo and fails, but this is part of Leo's whole scheme, for Leo permits Jin to "escape," and in the process "rescue" Mei before they can torture and execute her. The idea is that the riffraff swashbuckler who identifies himself to Mei as "Wind" will earn her trust by defending her from the soldiers sent to pantomime an attempt to "capture" them, and, in the meantime, she needn't worry about her virtue, for as "Wind" explains, she's no longer a prostitute, so he can't force her into sex anymore, which I suppose is a code, if hardly an especially enlightened one. Leo's hope is that she'll lead them to the Flying Daggers' headquarters, and there they can be taken unawares and wiped out en masse. It's a pretty good plan, but it goes awry once Leo's superiors override him, and start sending out actual war parties to hunt down the fugitives, meaning that Jin must either kill his compatriots or be killed himself. It acquires another wrinkle, too, for "Wind" has begun to fall in love with Mei, and Mei with him, even though Jin's entire mission is to destroy everything she cares about, and Mei already has a man waiting for her back with the Flying Daggers.

See? Simple. And though twists arrive, it never really becomes less simple, with almost no deviation from the aim of following three characters so featureless that I'd better call them "archetypal" to make it sound like they're smartly-written. But they get to where they need to go, demonstrating how much small gestures matter for isolated, lonely ideological warriors, and the perpetual adrenaline rush of being constantly at risk of having their heads cut off doesn't hurt. It's an effortlessly credible romance, growing at the same time Mei and Jin begin to realize that neither of the machines they belong to even slightly care about them. Jin recognizes this first, and Mei finds out when she reunites with her Flying Dagger paramour—curiously, he's the only man in the entire organization that we see, and there's otherwise a very matriarchal bent to the Flying Daggers—but his truer colors are revealed, and whatever high-minded ideals her leftish-oriented resistance group espouses, they're put into practice only in the sense that her people only keep him from completing a rape, while valuing his skills too highly to actually punish him, whereas they insist that Mei execute the man she does love herself. (This being, unfortunately, the one beat of the movie that—taking it as a strictly literalist proposition—does come off as slightly stupid. The other script problems are just the result of overclocking the melodrama: one of the film's two major twists is perfectly great, but the other big reveal calls into question what the point was in the first place, and even makes me wonder if I should reconsider how much I like a salient aspect of one of the performances, since while it involved a great deal of small but hard work, once the third act kicks in several scenes where that work was showcased don't make much sense.)

Daggers has been called apolitical, but I don't think that's right—you're probably presently failing the temptation to map this onto America, and in our context, it would obviously resonate differently—but I was shaken by how hard it is not to read the bitterest possible politics into it, given its actual Chinese context. For all that Hero is (unfairly and reductively) maligned as pro-PRC propaganda, Daggers comes off as a corrective, and maybe also a key to understanding its predecessor; it's not apolitical, I said, but it's also so nihilistic about power and ideology that I can see why people call it that, and it might not be the worst abuse of the term. In the context of a film about a group who are almost explicitly referred to as "communists," yet made under the People's Republic of China, that "apolitical" angle is shocking and even subversive, and by "subversive" I mean "actually subversive," rather than what Americans usually mean when they say something's "subversive."

But ultimately part of the sub rosa rejection of totalitarian movements is how inhumane they come off in comparison to the currents that really animate the film, which is, rape included but also rape aside, absurdly horny, and elemental about that too, though the very two-dimensionality of the characters has the profound effect of reminding you how much they've surrendered in order to be soldiers on opposing side of a war, and how much humanity this unexpected feigned friendliness has awakened in Mei and Jin. (For the record, the actors are all great at embodying larger-than-life lust, love, jealousy, and yearning for freedom, though if I had to rank them the rough descending order would be Zhang Z., Lau, and Kaneshiro, the latter being the weakest link perhaps only because he can't cry on command, but Zhang Z. and Lau apparently can.) And all of it is set against a wilderness essentially devoid of anything but two color-coded warring factions and the glimmer of possibility for something more. The American movie it reminds me of most closely is Last of the Mohicans—in tone more than plot, though a couple's journey through a woodland wilderness (remarkably, the balance of the film was shot not in China but in the Ukrainian Carpathians) while being hunted, and immediately pair-bonding in the process, would necessarily bring Mann's Mohicans to mind.

It is not, probably, as beautiful as Hero, but gets more out of less, and, with two hours to fill but a story that could probably be compressed into one, it's rather more willing to take on tangents, which means a lot of superb visual elaboration. That starts almost as soon as the movie does, which introduces Mei with a musical number—a Han era poem set to music—that winds up, with a rearrangement, the driving force of Shigeru Umebayashi's great melancholy score. (And it is the driving force: it is, objectively, a very repetitive score, but it latches hold of you anyway; I suppose that's another way it reminds me of Mohicans.) This shades into a complex piece of choreography involving beans and drums and sleeves—it makes sense onscreen—and then into the first martial arts setpiece of a film brimming with them, letting you know with Zhao Xiaoding's cinematography (in this case, starkly overlit and flat, though this remains the case only for this scene) and some downright Shaw studio-style cutting that Daggers is here to pay homage to old-school wuxia while still incorporating as much of the new as possible without making it feel like an alien intrusion of the future. (This does not prevent the occasional CGI overreach, but that really only becomes a problem during the finale, which leans a little too heavily on CG snow that is only a little more sophisticated than a photo filter. It also doesn't prevent the occasional cruelty to horses, Golden Age Western-style; they don't look like they got injured—they always get up—but they don't look happy.)

As far as Zhao's contribution goes, there aren't so many movies after Daggers, on either side of the Pacific, that look like it does; Zhang's next two movies certainly don't. As much as Hero leaned into the physicality of film, I think Daggers might do that even more, with a richness to the season-shifting landscapes and a softness that makes it look like a true artifact of the past; if it didn't have CGI, you would be hard-pressed not to assume it wasn't made in the early 1980s; but I would also, very hesitantly, describe it as indebted to King Hu and, more broadly, the graphic style in Chinese nature art, which is a lovely thing for a live-action movie to pull off. Zhang and Long Cheng's editing is likewise astoundingly good, with the story's emotions driven visually by forceful cuts (especially a pair of match cuts, one a soul-shattering match-dissolve, toward the finale) as much as the story or the performances.

Overall, it's surprisingly willing to present itself almost upon the level of a high-flying cartoon, without any of the self-importance that attached to Hero. But as that musical sequence might suggest, what it's most like is a musical—Zhang, in addition to his film work, has maintained an enormously successful career as a theatrical director in China—and its fight choreography comes with inordinately-regimented stylization. Wuxia films get compared to musicals all the time, and there's merit to that; the phrase "wuxia choreography" already implies violence communicated with elegant poetry. But Daggers goes further still, frequently into shots that are not dancelike but are just dance, with arrangements of human bodies that aren't about violence in any literal sense and are barely about it in a metaphorical sense—I could say that some are metaphors for social oppression, and sometimes this is obviously what they are, but in many instances they exist purely because their geometry is beautiful in its own right. This ranges from Zhang Z.'s surprisingly-athletic leg lifts (I mean, I knew she had stunt training, but she's legitimately strong—or it's wires, whatever) to the rigid synchronization that often attends the swordplay. All the more reason to think of it as a musical in Chinese action-fantasy form is how it evolves its essentialized romance with side-by-side combat, but then, the modes bleed over one another: the scene where Jin collects flowers for Mei from horseback in slow-motion is shot with as much flair and pomp as an action sequence.

But all of the above and more go into the film's centerpiece, an extended wire-fu battle in a bamboo forest that is obviously extremely in debt to Crouching Tiger—and, tenuously, A Touch of Zen, and doubtless a dozen other movies with bamboo grove fights neither one of us have seen—but also has different goals than its more proximate inspiration. (It does not attempt the same delicacy, but the aim here is mind-boggling spectacle.) This is what crystallized that whole "Hero B-side" thing for me, too, as this represents the first entry into Flying Daggers territory, and from the bamboo forest fight and going on for perhaps the next twenty minutes, this is Daggers' "Green Sequence," featuring the one major color that felt like an afterthought in Hero, now repaid with interest as we're treated to dark green men and lime green women fighting in a super-saturated bamboo inferno—only Jin, in his purple, is out of place—while the aggressive, obscuring vertical lines of the milieu inevitably evoke a prison. And those aren't even the best visuals in the film.

The best was, incredibly, arrived by pure accident, and though I've complained about "CG snow," you understand why Zhang had to resort to it—it's because he never intended the climax of his film to be a duel in the snow in the first place, it just actually snowed in Ukraine and he had to deal with it. He turned the crisis into an opportunity, and the result is impressionistic brilliance, a "turned a production catastrophe into a triumph" story to stand next to Harrison Ford's diarrhea on the set of Raiders. And so, at the end of all things, and in the very midst of the final clash, the autumnal landscape dissolves into a wintry wasteland. A dead and featureless field of battle, it's as ideal a backdrop imaginable for a battle between two souls who have, in every essential, died already. It's what seals the deal for House of Flying Daggers as one of the most image-driven and heartrendingly epic romances you'll ever see, which is a hell of a thing to be for a movie that is, at the same time, so full of the pure joy of making action cinema.

Score: 10/10

No comments:

Post a Comment