1946

Directed by Vincente Minnelli, Charles Walters, George Sidney, Lemuel Ayers, Roy Del Ruth, and Robert Lewis

Spoiler alert: inapplicable (and as I've said before, it's difficult to be brief with musicals or anthologies, and this one's both)

The early history of the film musical—indeed, the prehistory, given the submerged status of so many early sound musicals—can be summed up, reductively but probably not that inaccurately, as Hollywood's attempt to capture the spirit of Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. for the screen. Ziegfeld himself had been involved in at least one film which claimed to do exactly that, the impresario being credited with "supervision" over Paramount's Glorifying the American Girl in 1929, which I hesitate to judge too harshly because I've only ever seen the cut-down post-Code version of it. Still, though it might have some marvelous-looking two-strip Technicolor shots of nearly-nude Ziegfeld girls that I missed, I doubt that any version of it could overcome its core weaknesses, all of them stereotypical to early sound musicals, particularly a "dancing girl makes it" story so bland it barely checks the formulaic boxes, and a visual scheme so careless that the insult "filmed theater" would be insufficient, "filmed theater" at least implying "being filmed from on or around the stage, and not the twelfth row." Curiously, while it incorporates Ziegfeld's revue into its third act, the aforementioned plot means that this exemplar of the Ziegfeld Follies on the screen was not itself a narrative-free revue; that's very curious, considering that revues were all the rage until audience fatigue set in so hard that even something special like King of Jazz flopped, leading to the revue-style film musical almost completely vanishing by 1931, to be supplanted by, well, a thousand movies about dancing girls making it.

Despite the revue musical's extinction, it's probably impossible to overstate Ziegfeld's influence upon the genre (just the overlap of talent alone); and as for Ziegfeld's direct impact, that remains embodied in the film adaptations of Ziegfeld's musical plays, like the loathsome Whoopee! and Show Boat. But his legacy is most explicitly immortalized in the sort-of trilogy that MGM began with their 1936 Best Picture-winner, The Great Ziegfeld. That film was a Ziegfeld biopic with spectacular musical interludes, and in 1941 it was joined by Ziegfeld Girl, an archetypal examination of three of Ziegfeld's glorified performers. I love that this was the accidental scheme that MGM's Ziegfeld "franchise" stumbled into. The first, naturally, told the story of the man; the second told the story of the women; and, fittingly, it fell upon the third to be the show itself, only now with nearly two decades of formal development behind it, so that none of that "filmed theater" crap ever even comes near it. Okay, it's obvious in retrospect, so while I'll concede that The Great Ziegfeld's ending presented a substantial obstacle to continuing Ziegfeld's story, what with Ziegfeld being dead, it's strange that it took so long to figure out that the Follies that Ziegfeld produced were more interesting than the follies that he lived.

It was Arthur Freed who finally cracked it, he and a gaggle of directors managing to convince Louis Mayer to fund an anthology that would update the spirit of Ziegfeld for the 1940s. It would be a showcase for MGM's biggest contract players and greatest artists, and wound up taking forever to compile, so that (for example) the production of all of the sequences with the movie's let's-just-say-headliners, Fred Astaire and Lucille Bremer, actually predates the entire production of Yolanda and the Thief, Astaire and Bremer's flop with this movie's main director, Vincente Minnelli, even though that one was released a year earlier in 1945. Given this painful and drawn-out process, some ideas would necessarily wind up compromised. Some would be abandoned altogether. There's indication that a much longer version was previewed in 1945, only to be cut down. But Freed's foundational stroke of genius always persisted: Ziegfeld Follies actually is a direct sequel to The Great Ziegfeld.

This we discover in the film's introduction, which, leaning into the difficulty posed by its protagonist's death, simply begins in Heaven. Here we find Flo Ziegfeld (none other than William Powell, obviously!) lounging in his bathrobe in a well-appointed hotel bedroom suspended in a fathomless celestial void, the unavoidable conclusion being that Kubrick straight-up pilfered this imagery from a goofy musical revue but nobody's ever had the guts to say it. Flo spends his days remembering his grand life on Earth, memories conjured for us in the form of a stop-motion cartoon of low intrinsic quality but with some noticeable charm, at least up until the point that we get to the great Ziegfeld's greatest stars. Now we get a sense of the film's astoundingly blasé attitude toward the Follies' uglier edges—and this will indeed come back to bite us in the butt—when Fanny Brice's representative moment involves the comedienne shrieking "I'M AN INDIAN" in a "squaw" costume, and even that's arguably less bracing than Eddie Cantor's blackface puppet. (It's startling that a 1946 film seems more comfortable with this, and with racial antagonism in general, than its predecessor from a decade earlier.) Well, anyway, Flo's memories have grown stale—put simply, Heaven bores him—and he wonders what it would be like to do a new show. Who would he get? For starters, there's Fred Astaire.

Astaire offers a heartfelt encomium to his one-time employer, threading in an implicit disclaimer that this is a revue, and shall therefore not reach even the modest level of narrative integration that other early 40s musicals had achieved. As for Flo, he never returns, more's the pity; but they probably had to beg Powell to reprise his role at all.

Hence we go directly to the show, starting with the film's most classically Ziggyesque number, as you could determine from the title alone, "Here's To the Girls." Built around a Freed and Roger Edens song, it's a blast of hot babes in hot pink, introduced by Astaire, and initially centered upon Cyd Charisse's ballet—itself more of a stereotype (or even sexy parody) of ballet—though it ultimately cycles through a number of variations on its one idea before arriving at an imperiously pink Lucille Ball atop the Lone Ranger's horse on a carnival carousel. All told, "Girls" is pretty great, and definitively establishes what the general mood of Ziegfeld Follies shall be: it'll be profoundly sincere in its desire to entertain you, and it'll often ride a line between silly and genuinely beautiful, and it'll be about Technicolor more than most movies manage to be about anything. That's the Minnelli touch, and this time, I think he gets it almost entirely right. As for silliness and beauty, this sequence errs on the side of the former, climaxing with a bunch of cat-girls herded by Ball, wielding a whip. (So there's that.) Better yet, it's post-scripted with Virginia O'Brien, expressing comic discomfort with her huge pink ostrich headdress and riding atop a fake horse spinning on an unseen turntable that makes her look like she's hurtling through cosmic space. She sings a counterpoint to "Girls" with "Bring On Those Wonderful Men," a very funny thirst anthem that is, of course, never satisfactorily answered. Nevertheless, the Charles Walters segment, appropriately enough, gives it a bit of a go. (8/10)

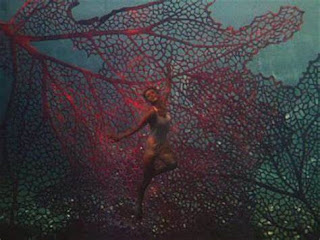

The next segment is equally Ziegfeldian in spirit (though I doubt it could be done on the stage). This is "Water Ballet," and though I think it must postdate Bathing Beauty, it comes off like the most prototypical showcase imaginable for Esther Williams's specialty talents, as well as what slow, dreamy underwater ballet could achieve. It's quite lovely, in fact: the smiling swimmer does her thing amidst a lushly-colored, hugely-artificial undersea realm, and it concludes with the direct equation of its star with a water lily flower. It's far from the most demanding or artistic thing Williams ever did, and I have some issues with the continuity editing, but the thing is, you never know with Williams numbers. It's best to relax one's standards over (for example) precise framing, or whether bubbles disappear between cuts, as Williams's art was always somewhat inherently dangerous. Besides, George Sidney (I think) accomplishes some breathtaking compositions of the submarine sensation amidst the fake coral anyway. It's relaxing, simple, and just-plain-nice. Bosley Crowther called it "sorcerous," which means Bosley Crowther got a hard-on, and, sure, why not? (7/10)

That brings us to "Number Please," a comedy routine. Ziegfeld Follies is burdened with these comedy routines. Yet I found their salience diminishing this time around; Follies is better on a second watch in general, as one is prepared for, frankly, just how much dead air it contains. (It helps when the more jarring provocations don't come as a surprise, too.) It's said the comic segments were directed by Sidney before Minnelli took over, but Minnelli might've had some input regardless, and I'll say one thing nice about them: whoever did them, they are sterling examples of that MGM trend of minimalistic color-based production design (think Vera-Ellen's introduction via daydreaming in On the Town). So they arrive as pocket universes rendered in big, bold blocks of weird color, decorated with as few props as possible, creating uncannily-empty dreamspaces that aren't even really "stagelike," as they appear to stretch out infinitely. This is the best thing about them, and this one is also the best example of that here, but, miraculously, it's not terrible otherwise. Detailing Keenan Wynn's frustrations over his inability to get a telephone operator to connect him to a local shop while other people in a notional "hotel lobby" have no trouble getting connected to the most far-flung locations on Earth, it's mostly right-sized, and has a hilarious final beat, and these are things you can't say about any of the other sketches. (7/10)

The next sequence heads into higher-browed territory, co-opting the drinking song from Act I of Verdi's La Traviata (it is titled, articlelessly, "Traviata"), probably the most famous piece of music from the opera. I am rather certain, going by certain aesthetic affinities, that this was another Minnelli segment, though the title card from the little book that introduces most of these numbers credits only Eugene Loring's dance direction and Irene Sharaff's costuming, which is fair enough as that's what this sequence is about. Taking place in the idea of a white ballroom, shrouded by innumerable streamers of gauzy fabric, "Traviata" introduces an idea that will return again and again in different ways throughout the film, with choreography that turns the chorines into cogs in a bigger machine, which is true of all choreography, but moreso here with its frequent use of stock-stillness in the background dancers, sometimes accompanied by their sudden, surprising movement. Likewise, it's a showcase for Sharaff's adornment of the bodies under her care, mostly the female ones—the men set the baseline color scheme of green-on-white, upon which the women can be wilder elaborations. There's a vague gesture toward "nature" as Sharaff's theme (besides the graphic suggestion of "ivy," there's the dress with the big gaudy butterfly attached to the bust), but mostly it's just providing Sharaff the opportunity to express a baroque maximalism and providing Minnelli-or-somebody-doing-a-Minnelli an opportunity to be elegant with his camera movement. It has a vague "love story" between its cameoing opera singers, James Melton and Marion Bell (Bell gets the discordantly crimson dress, making her the automatic center of any composition), but it's a song in Italian about booze. It's "classy," and a fine fashion collection, but perhaps slightly hollow on both counts. (7/10)

In between the two most graceful segments of the film, then, is its least, "Pay the Two Dollars," another comedy sketch, involving a businessman (Victor Moore) who gets arrested for spitting on the subway, and whose overblown lawyer (Edward Arnold) refuses to allow him to just pay the two-dollar fine, insisting instead that he spend thousands of times that to mount a legal defense. It's amusing up to a point, despite Moore playing it in the most irritating way possible with a permanent shrill whine. Unfortunately, it's one joke that seems to never end. Nor does it understand the concept of "courts of appeal," which I know is only my problem because I'm a lawyer, but I can't help but hate it. (4/10)

Its only use, really, is to serve as a buffer between the empty and hifalutin' "Traviata" and the equally-hifalutin' but emotionally-rich centerpiece of the whole film, "This Heart of Mine," using a standard by Freed and Harry Warren. I don't have to guess on this one: Minnelli directed the hell out of this, "Heart" playing to all his strengths as a shadow production designer and musical sequence director, while permitting him no opportunity to indulge his weaknesses. For starters, the base of its color scheme is marble white, offering no clash with the Valentine candy-wrapper theme of the rest of it, particularly the shiny spectrum of red-and-purple chorines who appear later. The human figures, principally Astaire and Bremer, are attired in mostly-black-and-white early 20th century evening dress, and while Sharaff has some fun with these costumes, as well as red accents and the occasional yellow dress, there's a splendorous unity to this that so often evaded Minnelli. The set design (this was plainly the most expensive thing in a very expensive film) bears Minnelli hallmarks in the best way, and if this is a Valentine, it's a faintly supernatural one, with a certain inhumane spookiness to the veiny branching of the white statues' candelabra arms and the white trees surrounding the "mansion" that it takes place in. There's a lot of mobile elements, including a moving walkway and a turntable, and it's all ravishingly well-choreographed by Robert Alton with, obviously, a lot of input from Astaire.

It has, furthermore, a story: Astaire is a con-man who steals into a rich persons' soirée in order to steal their stuff, and, having managed entry, he's transfixed by Bremer's debutante (and her jewels), and they dance right out of the ballroom and into the young woman's utterly-inorganic courtyard. Their routine is defined by remarkable symmetry, more than any other Astaire partner routine I can name (including others with Bremer), and it is fearsomely romantic in this regard, selling the idea of two lovers in tune, but at the end of the night, they must part, and Astaire's thief must complete his mission. Now we learn that Bremer's debutante has seen through him all along; she simply offers her necklace in recognition of his true purpose for being there, and it's heartbreaking to realize that she's played along with Astaire's literal song-and-dance because, even if his felicitations were fake, it felt real, and was better than the void she's lived in her whole life. (Bremer, though nobody's idea of a great screen actor, is frankly terrific in this.) I don't know if this sequence required a happy ending, but it certainly works when that ending comes; and, somehow, the film's most productively sincere piece also has by far its funniest gag, in the form of an image of Fred Astaire at his self-parodying goofiest (he looks like a Nazi count), adorned with a monocle and scowling as he turns his cigarette holder up at a hilarious angle while scheming his way into the party. Now, it bears some nasty choreography hiccups in the chorus that don't require much of an eagle eye to spot; but so what? "Heart" makes this movie more than just a curio. If it's not my very favorite Astaire sequence, it's real damn close. (10/10)

It was inevitable that we'd fall, but we fall pretty hard, into another sketch, this one at least featuring actual ex-Follies performer Fanny Brice. It's called "A Sweepstakes Ticket" and involves how her husband paid part of their rent with a ticket for the Irish Sweepstakes, which Brice has recently learned she won. They need to get it back and I'm bored thinking about it. If I value it at all, it's because it has William Frawley in it, and it has a decent punchline. It's probably the sketch that earns its length the best, because it tells an actual multi-step story rather than centering on one joke, but it still feels stretched-out. Alone amongst the comedy bits, it breaks their aesthetic; it's still sparse, but too much like a "real" space, involving camera movement through different rooms connected by doors and even, egads, walls. (5/10) Following that is the only really lackluster musical segment, unfortunately the one featuring Lena Horne performing "Love" by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane. The "black" one, it's set in a bar in an unidentified Caribbean locale, populated by unidentified Caribbean people who dress somewhat colorfully and own parrots and get into catfights, and sadly this is what "diversity" meant in 1946. Perhaps because MGM predicted that theaters in Southern states would cut the sequence entirely, they expended near-zero effort on it. It doesn't do anything. Horne sings the song. The song's okay and Horne can sing. The extras watch Horne sing. It has barely any noticeable choreography. Minnelli's direction is barely more than coverage. It's barely more than deathly dull. (5/10) Going for a hat trick of failure, the film alights upon another comic routine, Red Skelton's "When Television Comes." It's a pretty nifty conceit—when you have to accompany an advertisement with visuals, it can lead to humorous complications when the product is gin—but it's another initially-funny one-note joke driven into the ground. If you like Skelton rasping "SMOOOOTH!" at you over and over, be my guest. It probably inspired "Vegameatavitamin," which is exactly the same idea but, like, good. (5/10)

And now comes "Limehouse Blues," and that title inspires a certain trepidation. I hate to admit it, as it's cleaner to simply dislike anything this racist, but I've warmed on it slightly. So what we have here is a pantomimed tragic fable about a Chinese immigrant in Britain in the late 19th century. Of course he's played by Astaire. The story itself isn't terribly objectionable: the immigrant falls in love with a beautiful Chinese woman (Bremer), but she is used to the finer things, and he is poor. He notes a pretty fan in a shop window and fantasizes about giving it to his muse, but he cannot afford it; in the midst of this depressed realization, some (white) guys rob the place, and in the ensuing confusion, he's shot. That sends him into a dream ballet and though he comes out of it, he sees the woman on the arm of the rich man he'd seen her with earlier, and then he dies. Philip Braham's music is arguably more appropriative than anything else, just seizing on oriental riffs but maintaining a core of big band sounds, not really willing to test itself; Douglas Furber's lyrics, meanwhile, are given only to a (white) tavern singer, singing of Chinatown blues, and Minnelli does something interesting with that, making it diegetic (to the extent anything in this could be "diegetic"), a haunting voice heard through a plate glass window, almost a whisper in the sound mix.

So, anyway, what's striking about it is how hard they try to present this sincerely: the yellowface (on Astaire, not Bremer) is, on a technical level, almost persuasive. It's ultimately not, but even with sixty years of makeup technology development, it feels like less of a caricature than, for example, the Star Trek aliens in Cloud Atlas; my assumption is yellowface became a lost art. Which, you know, good, though this is barely in the same category as Mr. Yunioshi, or Fu Manchu, or Astaire's own previous adventure in race-bending in Swing Time. This is a testament to individuals who probably genuinely liked other cultures, and wanted to do something artistic with them, locked in an abominably racist Hollywood that had spent a quarter-century devaluing and, eventually, erasing the Asian-Americans who helped build it. (And that's not woke hyperbole: Anna May Wong was huge, and Sessue Hayakawa before her, truly one of the biggest stars of all time.) Well, the sequence itself manages (with great, unnecessary difficulty) to carry over its intended feelings. The dream ballet part, which is the balance of it, works better when it's Astaire in a black netherrealm chasing a glowing metallic fan through the specters around him; but it turns out he's been chasing Bremer, revealed in a blood-red spotlight. On this watch, I've come around a little to the garishness of Minnelli's sensibility, which arranges layers of solid color in planes one atop the other (I'm still pretty sure I don't like Yolanda and the Thief). At this point, Astaire and Bremer perform a precise and demanding fan dance that, unfortunately, resists attaching itself to the narrative, and so doesn't quite capture the tragedy of a love that couldn't be. Still, I like the starburst-shaped spotlight, and "Limehouse Blues," upon returning to the storybook poverty of the Limehouse set, at least concludes with some legitimate sexual melancholy; and hey, if nothing else, it seems to have the right opinion about racialized policing. (6/10)

Less problematically, now we find the Judy Garland number, "The Great Lady Has an Interview," which concerns itself with the dissatisfaction of a famed serious actress who'd prefer to be considered hot. The basic idea was to parody Greer Garson, who was offered the sequence for herself, but (perhaps predictably) turned it down. Of course, if you don't notice a subdued and mature sexual dimension in Garson's performances, then we're watching different Garson movies, but I see where they're coming from. Either way, Garland took it instead, and the absence of a mature sexual dimension makes it feel like what it is, a 25 year old in 1944/1945, who was still infantilized in most of her roles, playing at sexiness, while affecting an accent that makes her sound like she's doing a parody of Katharine Hepburn, which is what a kid would think "sophistication" was. In hindsight, then, it works best as an unbelievably charming take on Garland herself. And so the star-of-stars is arrayed in a slinky pale blue dress (that you can kind of see through), as she does a parody of awkward performative sultriness (that's still really hot), and the whole thing is shot through with mid-century camp, and my favorite kind of camp at that, where a gay perspective gently makes fun of heterosexuality and femininity while acknowledging the appeal of both.

Charles Walters, who for my money was the whole genre's no. 2 director in this era (Donen being no. 1), lays claim to this sequence as his real directorial debut prior to his feature debut in MGM's masterpiece of froth, Good News; Minnelli took over, perhaps out of some possessiveness regarding his wife (or soon-to-be wife, as I'm not sure when this was filmed). Well, we can split the difference: the design is Minnelli, as is the gold side-lighting (there's a joke on that subject recycled from, or recycled in, Yolanda), but the choreography is absolutely Walters, which necessarily dominates the segment's aesthetic. The wacky humor is surely Walters too, most prominently when the male chorus of reporters who've come to see Garland pops their heads in from the sides of her door and one of them turns out to be hanging upside down from the ceiling. It's a swell little sequence, borne over by Walters's characteristic bubbly energy, eventually becoming a rhythmic beat poetry kind of thing with no other music besides Garland's speak-singing and dozens of clapping hands, and I really adore the male chorus in this, not least the way Walters arranges all these friends of Dorothy in a reverent circle around the Great Lady. (8/10)

Competing with "Great Lady," however, for the film's most purely-fun segment, is "The Babbit and the Bromide." There's not much to say about it, except it's the only pairing of Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. I love it, from the way Astaire pretends (poorly) not to know who Kelly is, to the meta-vaudeville of "you mean this routine we've spent the last three weeks rehearsing?," to the physical comedy of the two kicking each other by "mistake." It's not either man at his best, and truthfully there's a homogenization of style to the routine (it was pulled from Astaire's stage version of Funny Face), so that, while you can see how each one's respective physique influences his style, it does tend to slightly flatten both as artists. But it's the only place where you'll see the two legends jitterbug together, and that's historic. (8/10)

Having made history, Ziegfeld Follies arrives at its finale, the most compromised of any of the sequences that remains in the film. This is "Beauty," by Freed & Warren and sung by Kathryn Grayson, of the big, high, and accordingly somewhat-unintelligible voice, but whom I've always enjoyed. It's a likeable song about, I presume, beauty, and again goes for a true Ziegfeldian ethos: in this case, babes in bubbles. It was originally planned as a much bigger number, with Astaire and Bremer, too; but the logistics fell apart, requiring a restaging and the truncated version we get here, which is still absurdly pretty, with (I assume) Minelli going all-out on rose and gold lighting as refracted through the infinite piles of soap bubbles that Charisse ballet dances her way through, eventually leading to a surrealist fashion-shoot landscape of metallic blues, populated by extravagantly-attractive and moodily-photographed women. It's a big enough finale despite the compromises, ending with ZIEGFELD FOLLIES in neon lights as Grayson hits the high note. (8/10)

Ziegfeld Follies has its flaws, that's for damn sure, and it's never a masterpiece besides "This Heart of Mine." But there's something about it that keeps growing on me every time I see it. It cost a fortune and lost MGM money because it couldn't do anything else; yet it sold enough tickets to suggest that, in more disciplined productions, its styles could be highly profitable. And they were; it even led to a miniature subgenre of neo-revues. It's a lot of movie, and I think enough to satisfy any connoisseur of the mid-century musical, even if a non-trivial portion of it's crap—and even if almost all of the rest of it is empty calories.

Score: 8/10

Reviews in this series:

The Great Ziegfeld (Leonard, 1936)

Ziegfeld Girl (Leonard, 1941)

Ziegfeld Follies (Minnelli et al., 1946)

No comments:

Post a Comment