1957

Directed by Nathan Hertz Juran

Written by Ray Buffum and Jacques Marquette

"The Brain From Planet Arous" is one of the great titles in mid-century sci-fi, so bluntly descriptive of the pulp pleasures that it promises that it rounds back into breathless huckster poetry. This 50s sci-fi film's title is on the level, too. No beating around the brain here: the titular monster is encountered by the middle of the second reel, and shall be a constant presence thereafter. Even the poster isn't bullshitting you this time: everything there is either as cool or cooler in the movie. But The Brain From Planet Arous is not only a title that tells you what this sci-fi movie will be about; it tells you precisely what breed of sci-fi movie it is.

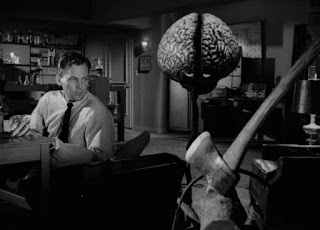

You couldn't ask for a finer representative of its particular strain. As Forbidden Planet is a perfect representative of proto-Trek cerebral spectacle, as The Incredible Shrinking Man is a perfect representative of science-mediated existential crisis, as Godzilla is a perfect representative of allegorical atomic devastation, The Brain From Planet Arous is a perfect representative of the junk sci-fi yarn, and I value it all the more because what it achieves is not valued enough. But time has been kind. To be remembered as well as Arous—either with fondness or derision or a mixture of both—is an accomplishment for any movie in its weight class. That inflatable brain prop with the sleepy glowing eyes remains one of the five or six most famous images in the whole genre—an emblem of the silliness of 50s sci-fi, second only (if second at all) to Robot Monster's alien gorilla in a diving helmet. For that matter, consider John Agar laughing maniacally in silver-painted contact lenses which make his eyes look like black pools of night—that might be another one of those five or six most famous images, and that's Arous, too.

Hell, I laugh at it myself. But it's an earnest, delighted laughter at the prospect that something so cheesy and threadbare and goofy can still wind up so watchable and effective. Arous is Robot Monster's mirror: another independent production released by an independent distributor who screwed the filmmakers, and it's even quite similar in its whole "alien gets hot for a human babe for some reason" plotting. (A distinction, however, is that you don't have to do much work on Arous's behalf to explain what that reason is.) But instead of turning into a catastrophe that could only be appreciated as garbage from the id, or as a mockable object that does most of the work for you, Arous wound up superlative in basically every way it could be, and not just for something on the low-budget shlock end of the spectrum, though being on that end of the spectrum is part of what makes it precious. I loved it long before I understood its production history, but its production history makes me love it even more: it was, and I use this phrase with sincere admiration, a film made by a bunch of losers.

They'd all been brought low by Hollywood, or had never been brought high in the first place, but they were all too talented to be losers. Producer (and uncredited writer) Jacques Marquette had created Marquette Productions mere months beforehand—Arous only being preceded at Marquette by a quickie J.D. picture in a Corman vein, Teenage Thunder—and his ambitions were reasonable. He never had dreams of drive-in moguldom. He was simply an underemployed camera operator who wanted to be a cinematographer but couldn't get the job, so he created a production company and hired himself. But before you get the wrong idea about how well-heeled Marquette must have been, one of Arous's major shooting locations was his neighbor's house, chosen because his neighbor had embarked upon a more responsible career path as an optometrist and, thus, had a significantly nicer home. And it's still a pretty normal home. And those silver contacts? Marquette also commissioned his neighbor to make major props for his film. Meanwhile, we have our star, Agar, the ex-Mr. Shirley Temple who'd been too foolish to realize his life was awesome, and who'd ruined his marriage and his career alike with resentment and drink. Agar's co-star Joyce Meadows didn't really have a career at all, still working at a diner with just one screen credit to her name. The major supporting actor, Robert Fuller, was languishing too: until joining Marquette he'd been toiling as a non-speaking extra for five years. As for Marquette's credited screenwriter, Ray Buffum, he barely appears in the record outside of Marquette Productions—none of these stories are unalloyed triumphs, mind you. But most had happy endings, and their protagonists all left a mark.

The one principal who wasn't a loser was its director, Nathan Hertz Juran—a sci-fi director now, but for Universal and for Columbia with Harryhausen, and therefore legitimate in ways Marquette wasn't. (So: to address the question of why Arous's producer-writer-cinematographer didn't just direct it himself, I give you Arous's double feature-mate, Teenage Monster, which Marquette did direct, and which is awful. The likeliest answer, then, was that the producer simply wanted Arous to be good.) Juran took the job because it paid, and perhaps they also wanted a "real" filmmaker who could interact with Agar as a dignified peer, rather than another loser who would only make him more depressed.

I belabor all this because it emphasizes what kind of film Arous is, and why it succeeds: imagine an Ed Wood movie, but it's made by actual professionals, with a leading man who was still alive, and, if your heart can stand the shocking facts, for less money (Plan 9, made the same year, cost two grand more than Arous's $58,000). It's a bit of a miracle even so; the other Marquette productions are deeply inadequate films. Yet this is low-budget programmer sci-fi taken to the very limits of the form. It's like a dream of what 50s B-movies could do, but almost invariably didn't, using a vanishingly small budget and primitivist effects and the lowest-fi tools of its trade to tell a story of intergalactic scope, and still selling that scope, despite its deficiencies—Jesus, despite barely leaving the house!—so that you feel like you saw something cosmic anyway.

That story then, concerns a sparkle that slams into the American desert, which turns out to be Gor (the voice of Dale Tate), an escaped criminal from a world described as one of pure intellect, in case his being a giant floating intangible brain didn't tip us off. He's possessed of mighty powers and malign purpose, but our man, Steve March (Agar), wouldn't know that—yet. All Steve knows now is that there have been strange flashes of radiation from the vicinity of "Mystery Mountain" (that placename says so much about Arous's operating mode, it's adorable), and he resolves to investigate alongside his reluctant, sci-fi-reading assistant, Dan (Fuller). It's never quite clear what Steve thinks he'll find out there, but he has a movie to kick off, and after lunch he says his goodbyes to his fianceé Sally (Meadows). He and Dan head to Bronson Canyon/Mystery Mountain, whereupon Dan's blasted with rays and Steve's body is seized by the brain from planet Arous.

As soon as he returns, Sally notes Dan's absence, and the change in Steve's behavior—in a nice little touch from Meadows, Sally even welcomes his new aggressiveness for about ten seconds, before Steve pushes it too far. If it weren't for her dog, he probably would've finished raping her in her own backyard. This is frightening, but even more inexplicable, and Sally and her father (Thomas Browne Henry) head out to Mystery Mountain themselves. They find Dan's corpse, and they find something else—Vol (also Dale Tate, also in two other roles; he was an associate producer). Vol is another brain, sent after Gor. He admits it will be difficult to apprehend Gor without also killing Steve, but he's willing to try. Gor, however, is already making plans for our Earth, and he's having a grand time mocking his human host's impotence, describing the empire he'll build and the pleasures he'll take with Sally.

It's a tale as might have been told in the pages of Astounding Science Fiction (and indeed had been, Marquette eventually admitting that he'd nicked the very basic premise from Hal Clement's "The Needle," though Arous is more elaborate). And, you know, if you were writing an alien fugitive/alien cop movie from these foundations, you would probably have Vol possess Sally as Gor has done Steve (except voluntarily), and structure it as an erotic (aroutic?) sci-fi thriller about Sally/Vol getting close enough to Steve/Gor to strike, ending up in an epic confrontation between two thermonuclear brains. In actuality, Vol possesses the dog. I think that's fine: it's cute, and it also makes this story about human agency, specifically Sally's agency, almost the very instant it threatens to take it away, awarding the hero's duties to Sally as Sally. Accordingly, we wind with up something like an erotic sci-fi thriller anyway, with Meadows putting on the kind of facade that only an alien wouldn't see through, though it's a good performance anyway; a more pervasive subtlety wouldn't fit the tenor of the film, and it's sufficient that Meadows puts a sensitive spin, for example, on her non-explanation of her attempted rape to her father. It works for her major scene partner, too: Agar actively stresses the prospect of Sally's confusion and disgust as something arousing to Gor in itself, with a constant murmur of "oh, you'll see, you'll see" in their dialogues together.

Still, if there is one thing here that's a problem, it's Vol, the worst cop in the universe. He exists solely as an efficiency: a channel for vital information that Sally probably could have learned by other means. Otherwise, Vol does nothing, and the conclusion you're left with is that for all his self-promotion regarding "powers that equal and surpass" Gor's, he's a frightened coward who's wholly content to allow humans to do his job. (I don't know if it's more than a loose thread, but Gor's world-beating super-terrorism doesn't change Vol's or Sally's calculus, either.) I might have preferred if they'd built two brain props, as well, but that's asking too much; I would not have gotten another voiceover actor, and even though Tate's using exactly the same echoey, electronically-modified voice for both brains, there's such an instantly-identifiable difference between his wicked, lewd Gor and calm, placid Vol that I spent a long stretch of my life under the impression there were two props, each with subtly distinct "expressions."

So I don't know: there's something about these bargain-basement in-camera special effects that just works. Not everything is a winner, obviously, though even at their worst they're crappily charming: the airplanes are crummy models, for example, and when Gor blows 'em up with atomic telekinesis and/or firecrackers, you can see pieces of debris spin in the air, still attached to the string. But for the most part the effects barely represent anything besides what the narrative says they are—bright flashes of light, appliques for radiation-burned flesh, a double-exposed brain prop that is, after all, supposed to be translucent. Even the stock footage is uniquely well-integrated: when Marquette takes recourse to atomic bomb test footage, it represents Gor blowing up an atomic bomb test range. This approach betrayed Marquette on his very next project, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, which looks idiotic. But while I'm not sure even one single effect in this film could not have been accomplished as early as 1900, every single one looks neat and, if not fully persuasive, then as a plausible stand-in that gets the idea across with dreamy nostalgic enchantment, like every effects shot is trying to be the not-quite-representational cover of a pulp magazine. It's movie magic at its most foundational, yet applied with surprising discipline; it's absolutely perfect for a film that Marquette clearly designed around turning his limitations into strengths.

I keep saying "Marquette." I think of Juran more as a technician than a director—he wasn't Harryhausen's guy because he was some profound storyteller, but because he understood the necessary math—so maybe that's why I persist in believing that Marquette was the more vital force, even if I've seen the dismal results when he did direct. At the very least, Arous was Marquette's baby, but Juran wouldn't even put his surname on it (he used "Nathan Hertz"). It's difficult to say, then, who earns the credit for anything in particular: was it Juran's idea to do the iconic "watercooler shot" of a distorted Agar in his silver contacts, or was it Marquette's? Marquette acquits himself well as far as that photography goes, anyway, and Juran as far as his direction goes, with a lot of misty atmosphere in the cave sequences, a clear eye for effective angles and shot scales, and strong camera movement, despite most scenes occupying the standard "brightly-lit room with some science stuff in it" aesthetic of contemporary sci-fi cinema. The finale in particular, where we at last see Gor's true, vulnerable form (and so for the first time the prop comes on-set), opens up with a terrific little piece of editing and composition, a push-in on Steve collapsing into his chair in agony before he learns a crucial piece of new information, and a reverse angle pulls out not just to reveal the hovering brain on wires in the midground, but to reveal Steve's ax as the object dominating the foreground.

It's solid audiovisually, too: an unusual proportion of the film receives a musical score, courtesy Walter Greene, and it's one of the best of its era, conjuring up eerie sensations out of woodwinds and percussion, and finding the exact right mood of jolly, pompous menace for Gor. The point is how remarkably well-built it is, and not even really graded on a curve. That applies to Buffum's script, too, which is just the most wonderfully arch thing, larky and stolidly funny until the brains arrive and things get going, whereupon it tightens up considerably. But, above all, that script offers a platform for the film's best special effect, namely John Agar.

And Arous would be valuable even if all it had was this performance, which must be Agar's best in or out of sci-fi, representing one more limitation that Marquette redeployed as a strength. To be clear, I adore Agar, and not solely for this movie; but about the only times he didn't play his lead roles as complete fucking jerks was when he was checked out completely. "Steve March" is one of his nicer sci-fi characters; of course he's not usually "Steve March." For a movie so intent on being about itself, Agar's participation gives it actual thematic heft, and whether by accident of casting or not, Agar turns the film into secret satire: he'd played plenty of science heroes before, but now Agar's a science villain pretending to be a science hero, and he's an extraordinarily good villain, essentially just by being himself.

Certainly, Agar doesn't bother much with a second character—the idea that he even discussed Gor with Tate is almost undoubtedly a fantasy—and the closest he gets to anything like it is that Gor/Steve is sometimes fidgetier, and as much as this is a dramatization of Steve's internal psychic war, it's almost as easy to attribute to those silver-coated contacts, which caused Agar enormous suffering (those beads of sweat, anyway, are likely quite real). But it's a top-tier performance even so, the bleedover between the two characters permitting an inference that Gor has unleashed Steve's unconscious while enslaving his body, and there's a whole undercurrent of a War of the Worlds-by-way-of-Freud here, that Gor really would've been unbeatable, if only he weren't constantly tripping over Steve's dick. Thanks to Agar, Steve/Gor becomes a twisted parody of a smarmy 50s scientist, not-so-secretly lusting after power, and even-less-secretly just lusting, a being of "pure intellect" whose primary mode when not being a despot is being a sex maniac. By the same token, the story becomes a wish-fulfillment fantasy of abuse, where it turns out your boyfriend tried to rape you and take over the world because he's possessed by a horny brain, actually, and only you can save him.

But maybe this overintellectualizes it, and misses the real point, which is that Agar's grating smugness amped up to cosmic scales is a blast. Maybe his storied resentment even helped: Agar's Gor is radiant in his beautiful contempt. Agar hits every beat, from Gor's fits of laughter, to the even better moments where Gor is "in character" as Steve and trying (poorly) not to laugh at us "puny Earthlings," to the scene where Gor lays it on the line to the governments of the world and Agar's sneering sarcasm makes it so easy to forget that he's just on some shitty, minimally-dressed set, and the "governments of the world" are represented, inter alia, by some white guy in a turban, and he's not really a space brain, having way more fun being eeeeeevil than you or I will ever have doing anything.

Score: 10/10

That which is indistinguishable from magic:

- The central sulcus, or fissure of Rolando, Gor's weak spot, is indeed a real part of the human anatomy. The human anatomy.

- It must've been a desperate thing to convene an immediate meeting of world governments given the transportation technology of 1957. I like that Gor laughs at their inconvenience.

- John Agar blamed his late-life glaucoma on the contact lenses, but John Agar's not a doctor.

The morality of the past, in the future!:

- Of the few things in the film I dislike, the biggest is that dipshit final line to Sally, in reference to the second, good space brain that Steve never meets—"You and your imagination." I don't know if Agar fucked up the read, but it's basically just a sexist noise, given [gestures at whole movie].

- It had never occurred to me till this viewing, but now I earnestly wonder if immediately after our happy ending, Steve spends the rest of his life as a guest of the U.S. government in a dungeon under the desert.

- When Vol comes for another secret conference, Sally and her dad have put on their church clothes to meet the space brain. Frankly, I'm pretty sure this movie knows it's funny.

Sensawunda:

- Sensawunda is all over the place, despite or perhaps because of the sheer pulpiness. It's backgrounded, and we never see Arous, but we get a profound sense of the scale of the new universe we've entered. I especially love Gor's exposition of his plans to the assembled world leaders, casually removing humanity from the pinnacle of creation when he explains that once he's built his star fleet and conquered Arous, he'll probably be content with returning humanity's freedom and just letting Earth "live out its miserable span as one of his satellites," for we simply are that unimportant.

No comments:

Post a Comment