1988

Directed by Julien Temple

Written by Julie Brown, Terrence E. McNalley, and Charlie Coffey

Don't look behind the curtain, for it only complicate matters: everything about Earth Girls Are Easy, gorgeously messy as it is, screams that it was the result of something eccentrically passionate and uniquely idiosyncratic, and the author of its passion and idiosyncrasy is of course easiest to identify in its co-writer and co-star Julie Brown, who was also effectively a co-producer, at the time married to one of its actual co-producers, who was also one of her co-writers, Terrence McNalley, though she's made it known since she'd like you to mentally delete his screen credit. And perhaps I should also mention that Brown's film, Earth Girls Are Easy, is based on Brown's song, "Earth Girls Are Easy," from her 1984 album of novelty music, Goddess In Progress, which forms the backbone of the music in this film musical as well as in the later stage musical, which Brown helped create in 2001. So you can see why I'd be prepared to locate in Brown the visionary here, because it would be pretty to think that her colleagues were only there to help convince Vestron Pictures to pony up $10 million to pay for one woman's manic sex fantasy. It's compromised in one fairly obvious way—Brown is a bigger factor in your childhood if you're a 90s kid than you might notice (lots of voice work), but that was in the future, so it should not shock you to learn that when this aspiring entertainer wrote a film musical, she optimistically wrote the lead role for herself and she didn't get it—yet nevertheless it feels like not many other compromises were made getting it from Brown's id to the screen.

That's not the actual history of it, and that kind of disappoints me, not because it works to the detriment of the film (the film's still the film), but because that imagined person who came up with all of this by herself would, with minor cosmetic differences (and vastly more talent, discipline, and drive), basically be me. It's kind of staggering, considering how well its various influences dovetail together, to realize how separate the two currents are here, and that half of the movie is an overlay onto the other half: watching it with this in mind, it practically knocked me off my moorings to realize how astoundingly little in the screenplay itself demands, or even strongly suggests, that the pervading mood of the film would be "50s science fiction parody," and this was, it turns out, exclusively the idea of its director, Julien Temple.

The sole (and entirely paratextual) exception is that you might get a vague sense of "50s sci-fi" imagery from Brown's original album version of "Earth Girls," which Temple or Brown or Vestron replaced for the opening credits sequence with a new version, sung by a different person with entirely different lyrics, for reasons that are pretty obvious if you've heard Brown's original, which describes the act of interspecies lovemaking in unnervingly strong detail. It's delightful and gross—for that matter it's just straight-up better as music—and the film is lessened by its exclusion, but what it indicates is that Brown's chiefest point-of-reference wasn't cardboard science but Weekly World News-style alien abductions, specifically a woman's claim that a gray violated her after having snuck in through her doggy door. Of course, Temple, with Brown's cheerful assent and some rewritten lines, oriented things towards decisively different iconography, something rather more adaptable to romance, inasmuch as Jeff Goldblum's bedroom eyes shoved into a blue fursuit are, still, Jeff Goldblum's bedroom eyes. The weird thing is that the original lyrics of "Earth Girls" are startlingly close to still being the plot of Earth Girls.

Thus does star-crossed romance find its way to Valerie Gail (Geena Davis, and not Julie Brown), salon worker and quintessential Valley Girl ("Valerie..." oh, I get it), in that she's worrisomely stupid but also sweetly sincere. This is perhaps part of her present problem, in that when her fiancé, Dr. Ted Gallagher (Charles Rocket), for utterly unknowable reasons stops fucking his fiancée who looks like Geena Davis, she redoubles her efforts, intending to surprise him with a tawdry-glam makeover courtesy her salon colleague Candy Pink (Brown) and with sex she learned from self-help books. Instead, she stumbles her way into discovering a tryst with one of his colleagues. She throws the bastard out, but he's barely driven off before she hopes he'll come back. As luck would have it, however, a better man's on his way. In space, an interstellar ship suffers a catastrophe, which is a nice way of saying that two of its vibrantly-hairy crew members, Wiploc (Jim Carrey) and Zeeblo (Damon Wayans), broke their ship during a scuffle over who got to use the telescope to ogle babes on the planet below. Their leader Makelsolakveder—more conveniently, Mac (Jeff Goldblum)—attempts to salvage the situation, but down they go, crashing into Valerie's pool. Despite Valerie's initial terror, they turn out to be nice, so she's willing to help them lay low until they can repair their vessel. To this end, she has Candy restyle them, and it turns out her new pals—especially Mac (Jeff Goldbum)—are hot.

That's a longish paragraph but that's basically it: while waiting on the pool to get drained, Valerie and the trio have low-impact scrapes, sometimes involving Dr. Ted, sometimes not, and Mac falls in love with Valerie and Valerie falls in love with Mac. And we might as well get into the problems—"gorgeously messy," I believe I said—and they are many and they mostly don't matter, though they add up. For starters, it does not have a third act. There's a final third, and there's incident in it—the movie is never without incident—but none that in any sense grows out of the narrative convolutions of the first two acts, largely just whatever unstructured slapstick Brown and her co-writers can come up with to generate enough movement to serve as the last thirty or so minutes of a comedy, involving a spontaneous trip to the beach and various misunderstandings on the way back or, possibly, on the way there, for it's even slightly confused about that.

But it's not a plot movie, so I might count this instead as a strength—imagine Starman with none of the time-consuming paranoid thriller parts. What began as shenanigans with fun cartoon characters ends as shenanigans with fun cartoon characters, and I'm awed by the sheer tininess of the film's scale. Leaving aside the emotional throughline, the stakes amount to the all-important question of whether or not a pool gets drained (it does). To the extent the screenplay ever threatens our visitors with any consequences, it removes that threat almost the instant it's made. It's frankly surprising the movie even manages 100 minutes, it's so gossamer and slight—it may be 100 minutes, but the script couldn't have been 50 pages—but it fills that up with sunny vibes and enjoyable jokes and fun music (we'll get back to that). And yet I'm not entirely certain it has a second act, either, calling into question whether it even has a first, though it must, I just summarized it.

There's a feeling of it all being spitballed together—not unpleasantly, but even the very heart of it, the interstellar romance, is arbitrary fiat. Of course, that's just the most salient case of how every relationship in the movie gets treated, insofar as none of them exist within a narrative framework of characters who have any particular motivations or agendas, and so practically every single relationship in the film is essentially a creature of the rapports formed between individual actors in individual moments, and it's very lucky that its central relationship came pre-loaded with Davis and Goldblum, presently still idyllically married. There's almost nothing regarding Mac and Valerie as a couple before they, ahem, couple—the aliens can barely communicate outside of inappropriately quoting things they heard on TV (and the "seduction" here is "Mac takes off his pants," causing me to ponder the thoroughness of Candy's work)—yet there's still legitimate heat, and even warm coziness, for Goldblum has laid the basic foundation by occupying almost every close-up he gets with half-shy, half-smoldering gazes at his wife.

I belabor it because I wonder if one of the reasons Earth Girls persists more as cult object than everybody's-seen-it classic comedy is that it's such a hang-out movie its characters barely actually hang out. The obvious comparison is Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure and on one level that's exactly what it is, Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure For Girls (or rather Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure For Adult Women, as Bill & Ted has an unmistakably virginal cast to it that this film absolutely does not). Its humor, too, is driven by wall-to-wall idiots and an affectionate mockery of the same Californian subculture; its going-ness is likewise delectably easy. But while there might be a precious little romance here if you take it as it is, there's hardly any character dynamic to latch onto, within that romance or without. Sometimes Wayans and Carrey find a wavelength together; but it's hard to describe Valerie's best girlfriend, in particular, as even a real participant, rather than an occasionally-seen tertiary figure, and that's after Brown rewrote the part to change Candy from male best gay friend so she could exist in her own film at all.

But it survives its characters' random shuffling-around. To a great degree that's because Temple is directing the fuck out of it—not necessarily always directing it well, but with a great feverish energy, patterned on 40s cartoons and 60s comedies but all-80s in the most downright palpable ways. Depending on what aspect of Temple's direction you're looking at, he does a great job: the execution of the 50s sci-fi pastiche with a literal "you can see the wires" aesthetic is strong—take the fact that the aliens are actually about six inches tall (mainly an excuse to fit a starship into Valerie's pool), so to interact with humans they use size-changing technology sometimes, which is such a perfect parody of 50s sci-fi pointless clunk that it's even more amazing to realize it practically goes unnoticed by the script. It benefits, too, from defaulting to that intoxicating late-80s bright colorfulness, kicked up a few more notches to better capture the eye-searing vividness of our aliens' Technicolor-themed fur. (In fact, the single biggest disappointment of the film is that they take no opportunity to play with the aliens' natural hairiness, or even use their color schemes much beyond a blue sequined jacket, once they get their shaves.)

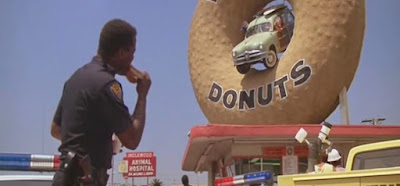

But it still benefits a lot from costume designer Linda Bass's the-80s-are-the-slutty-50s take on the clothes, and benefits even more from having the good fortune to nab the extravagantly-great production designer Dennis Gassner at more-or-less the beginning of his career. It anticipates The Truman Show, and not just because Jim Carrey's in it: it's a deeply artificial world he's built with Temple's nodding approval, but artificial in the way we imagine the 80s in the San Fernando Valley to have actually been, hence utterly natural and correct at the same time it's heightened in every possible way to be more of an Angeleno caricature, from redressing the Griffith Observatory as a happening nightclub to the garish suburbia of Valerie's pastel home, altogether an immortal dream of 1988 on the dot. (If it reminds you of Tim Burton, too, that's not just because Geena Davis is in it. I knew Temple directed Tom Petty videos, but it shocked me to discover he didn't direct "Don't Come Around Here No More.")

Brown's intention to make it a musical largely pans out: the numbers that are here are mostly good, though they peak as cinema immediately with the bouncy editing of Valerie's makeover, "Brand New Girl" (unless by "cinema" you mean "Davis walking around in lingerie," in which case it still peaks early, with her post-break-up number "The Ground You Walk On"); they peak as funny novelty music with "Cause I'm a Blonde," a hate crime/grievance anthem against fair-haired women that gives Temple the chance to expand his repertoire to a pastiche of 60s beach movies, though it has nothing to do with anything. The film already gave up the ghost of being an integrated musical with "The Ground You Walk On," and though it retains some musical-ish fillips that arise out of the strangers-in-a-strange-land scenario, which Temple and composer Nile Rodgers handle with some rhythmic, choreographed flair (Rodgers is also one of the vectors for that 50s sci-fi feel, with his electronic tonalities and Invaders From Mars homages), this really only leaves the dance-off Wayans gets with Crescendo Ward at the club, which has only slightly more to do with anything. So in addition to 50s sci-fi, it's also 40s musicals, though it's unfortunately terrible at it here, and you would never guess from this sequence that Temple had even seen a music video, let alone directed several. (In fairness, he was rock more than pop.) It's just all wrong, from a set clearly built before the sequence was designed, so that its clutter is constantly in the way, to the bumbling confusion about how to fit challenge dancing with frequent vertical movement into a Panavision frame.

And Temple does have his shortcomings: he can be drunkenly vigorous, but he's a lousy storyteller sometimes, blithely permitting numerous little gags and details to get buried by the editing (this movie had a gruesome post-production) as well as the general loudness, despite plainly believing he has communicated these details—the one that sticks out is Mac's electric shaver, which is also a plush animal, though I think this functionality is just foleyed in, and either way it's never established—and I could almost be talked into believing Temple did not know what an insert shot was. And even so: Valerie's reference-heavy black-and-white nightmare sequence is a terrific little exercise in nostalgia repurposed as surrealism, and the more I think about it, the more I approve of Temple's incongruous conflation of Cocteau's fantasy, Beauty and the Beast, with Forbidden Planet and Earth vs. the Flying Saucers.

It's more appropriate than it seems, emphasizing the fairy tale essentialism that the shaggy conflict-free comedy never really obscures. But it's a very contemporary fairy tale, is Earth Girls: when I said this is a film where "characters don't have motivations" I was, rather willfully, missing the point. They are motivated in the extreme: they are horny. The title, perhaps the greatest title in film history, says so. It is one of the horniest movies of the 1980s—of the 1980s!—and there's such a disarming sincerity to that horniness, balanced on one hand by Brown's lovely "a quiet guy who looks like Jeff Goldblum comes from outer space to fuck you with psychic sex powers (they also have psychic sex powers) and literally twice the heart of any earthman" wish-fulfillment fantasy, and on the other by Temple's own smorgasbord of visual sexuality, from Carrey and Wayans lunging like Tex Avery wolves at surprisingly-receptive Earth women (they are easy!), to the earnest artsy eroticism of Valerie and Mac's encounter, to the sly joke Temple makes with an "aerobics" video that was, in fact, produced by Penthouse, to the basic fact that Davis spends, without exaggeration, fully 30% of this movie's 100 minute runtime nearly naked, reminding me how statuesque Davis is, though I will stop with "statuesque" because I have cause to doubt that Davis would appreciate anything further. I've probably sounded like I've been complaining a lot, but I've only attempted to maintain some critical detachment; at bottom, I adore this silly thing.

It's also just plain funny, and occasionally pointed in its the satire of a certain strain of young adulthood in a certain place and certain milieu wherein only sexual pursuit exists and not even much sexual retreat, where "not having sex for two weeks" is presented as a relationship problem of apocalyptic portent, something I couldn't help but be faintly annoyed by till a callback (Candy uses it to explain Valerie's brusqueness to her friends and they gasp "two weeks!") confirms it was always a hilariously bitter joke. Moreover, Brown had love for Valley culture but in the way that recognizes that in exaggerating its superficial idiocy what you actually do is elevate it into an ethos almost profound in its sheer simplicity. Valerie, in particular, is honestly kind of a real moron, to the extent I wondered if Davis wasn't miscast, but it takes intelligence to play dumb this sharply—it's a generous performance, not least for the walking-around-naked-for-days-on-end part, but also because it's so self-effacing—and Davis puts more technique underneath it than you'd expect a role like this could possibly afford. (Consider the scene where Mac and Valerie have been arrested and he uses his psychic sex powers to turn the cops into 80s gay stereotypes and reveal their secret love for one another, which for what it is is astonishingly well-acted by Davis, playing three different shifting emotions all at once: relief she doesn't have to enact her plan of seducing the cops herself; slight disappointment that she doesn't get to prove she could seduce the cops herself; and heart-warmed satisfaction that these two guys found each other.) Wayans and Carrey shoulder the majority of the wackier comedy here—they are ably joined sometimes by Michael McKean's surf bum—and Carrey especially gets an early showcase for his peculiarities. I'd like to say that in preparing for the role he thought deeply and seriously about how a horny alien would behave, but... well, I don't need to finish that observation.

But everyone is wacky and moronic in the register that best suits them; there's a joyous purity to Earth Girls that's awfully hard not to respond to. Hell, the basic fact that Valerie is so ordinary (sub-ordinary!), but good-hearted and yearning, and is therefore and for no other reason rewarded with a cosmic sex god, could be the fundamental secret of its success. Everyone deserves their dreams, don't they?

Score: 9/10

No comments:

Post a Comment