1945

Directed by George Sidney

Written by Isobel Lennart (based on a story by Natalie Marcin)

In 1944, Gene Kelly, the face of the MGM musical, achieved his first real breakout performance, not at MGM, but at Columbia, with Cover Girl. Starring alongside Rita Hayworth had obviously helped, yet Cover Girl raised MGM's estimation of the singer-dancer-actor-choreographer they'd bought from David O. Selznick a few years earlier, but whose utility to the studio had been slightly obscured by the fact that his biggest MGM hit, For Me and My Gal, was itself more easily attributed to Judy Garland. Cover Girl isn't much to write home about, but even if I'm not really sure why it made money, it absolutely confirmed Kelly as a talent to nurture—and indulge.

Most everything that's worthwhile about that film flowed from the imaginations of Kelly and his then-frequent-collaborator Stanley Donen, above all a new, fully-cinematic brand of choreography in "The Alter-Ego Dance," which placed Kelly in pas de deux with his own double-exposure. For those few minutes, Cover Girl's frankly great, and I can imagine how it tantalized somebody at MGM: producer Joe Pasternak makes the most sense for our present purposes, though it could've been Arthur Freed, or both; I would have to assume that the decision to position Kelly as Fred Astaire's rival and potential successor in their segment of Freed's Ziegfeld Follies was the direct result of Cover Girl, and I think it must've been the first thing Kelly shot upon returning to MGM. I expect "The Alter-Ego Dance" prompted them to ask, "Gene, why aren't you doing this for us?" They may have had to ask him by wire, however, since Lt. (j.g.) Kelly spent a good part of 1944 in the U.S. Navy, working with their film service in Washington D.C., which had the effect of sharpening his desire to make movies, rather than just perform in them. Pasternak gave him such an opportunity in 1945, and Kelly (alongside an uncredited Donen) directed his dance numbers in his next film for MGM.

Appropriately, this was Anchors Aweigh, a film about American sailors starring someone who was (I believe) still technically an American sailor while he was making it. It took Kelly from rising star to actual icon; it's probably the film most responsible for making the most representative image of the Golden Age musical a tap-dancing sailor on leave and on the make. (1936's Follow the Fleet didn't, and if you thought about Astaire for a whole hour you might still never get around to thinking "a guy in dark blue bellbottoms dancing with other guys in dark blue bellbottoms," certainly not the same way that this might be the first thing you'd think of with Gene Kelly—which probably sums up the aesthetic distinctions between the two biggest dancing stars in Hollywood history better than a whole scholarly monograph would.) Anchors wasn't just a big deal for Kelly, either: it was his first of three pairings with Frank Sinatra—who with this film attained full-on movie stardom himself, in addition to his extrinsic fame as a singer.

Of the three, I'm not sure which consensus considers the best—on the basis of Vera-Ellen's participation alone, you could make a very persuasive case that Kelly and Donen's joint feature debut, 1949's On the Town (where Kelly and Sinatra play sailors again), is the better dance movie; meanwhile, if you liked Anchors but really would've preferred it with baseball players and directed by Busby Berkeley at his most indifferent, then I guess Take Me Out To the Ballgame (also 1949) could, conceivably, be your favorite. I'm happy to call Anchors mine, which still does not necessarily make it especially good. Yet I keep second-guessing whether I merely like it a lot, or actually love it. I guess I'll find out, though it's surely got enough problems.

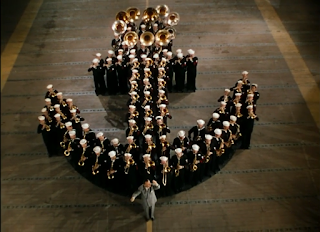

It begins pretty great, however, sounding off with a rendition of George Lottman's 1926 revision of "Anchors Aweigh" (the one that made it "the song of the U.S. Navy" and not "the song of the U.S. Navy football team"), which director George Sidney uses to establish probably the most noticeable aspects of the film's identity as an audiovisual object besides Gene Kelly himself. The "audio" part manifests in a surprising amount of not just preexisting music (that's not unusual), but music that you wouldn't ordinarily think of as coexisting alongside the original songs of a musical romantic comedy. But it starts with a Navy fight song, and only expands its ambit from there, with classical pieces (Brahms, Liszt, and Chaikovskiy, the latter misidentified as Freddy Martin with the shrug, "these guys all steal from each other"); tangos; traditional Mexican music; and even more Chaikovskiy which, thanks to Kathryn Grayson's coloratura soprano, goes opera. Meanwhile, the "visual" part is Sidney's mid-40s fetish for making sweet love to musical instruments with his camera. Hence this opening number with an enormous naval band aboard an aircraft carrier, and while it requires dozens of people if those instruments are going to make any noise (and since this is a movie, it only really requires them because if they weren't there, the instruments would be sitting on the ground), the actual subject of any given moment is "twenty trombones" or "twenty saxophones." It's more-or-less picking up where he'd just left off in 1944 in Bathing Beauty's trippy band numbers, using framing and choreography instead of light and shadow to create geometric collages out of an abstracted idea of "musical performance," and while there's something owed to Fantasia (and probably dozens of jazz shorts from the 30s and 40s, which is where I suspect these notions were first invented), in the mid-40s Sidney seemed to enjoy finding interesting ways to film people making music, maybe as much as he enjoyed filming "musical numbers," as such. This opening, anyway, isn't even the most forceful expression of that joy here; far from it.

For now, though, we should get past the first three minutes. So: that naval band has assembled under José Iturbi (the conductor plays himself) to celebrate their return to Los Angeles after a long stretch of action in the Pacific, as well as to honor the achievements of one sailor in particular, Joe Brady (Kelly), who receives a nifty medal for saving the life of his pal Clarence Doolittle (Sinatra). In recognition of Joe's heroism and Clarence not getting blown up, the pair are given four days' leave ("we hate to leave!" they smugly sing to their fellow sailors stuck on the ship in an assholish duet by the same name). Joe's eager to see his sex friend, Lola, so eager, indeed, that during his telephone conversation with her he's practically fellating the receiver, in a tightly-framed close-up that I rather like in its willingness to rub your face in Kelly's almost-drooling horniness, though if I had to see it on a sixty foot tall theater screen in 1945 I might have a different opinion. Well, that sets up Joe, but when Clarence calls his "girl," we're made privy to the fact that he's just calling information. Thus when both are unleashed on L.A., Clarence follows Joe around. Invoking Joe's debt—"you saved my life, so I figure you owe me something!"—he finally cajoles Joe into instructing him in the art of getting laid.

This doesn't even begin to pan out, however, for suddenly both sailors are dragooned by the LAPD into trying to talk some sense into six year-old Donald (Dean Stockwell), a semi-orphan who's run away to join the Navy. They wind up bringing Donald back to his aunt Susan (Grayson), presently working as a background extra in the movies (MGM movies, of course!), though she aspires to actor-singer stardom (and this was Grayson's breakout, too). Clarence falls immediately into puppy love, and soon he's contriving ways to trick Joe into continuing to play wingman, which is annoying but also difficult, thanks to Clarence having roughly the same emotional age as Donald. Despite his misgivings, Joe hatches a scheme—a fairly dastardly one—to ingratiate Clarence to Susan, by vastly exaggerating how well Clarence knows José Iturbi (that is, at all, as Clarence doesn't even recognize him later) while claiming that they've definitely managed to secure Susan an audition with him at MGM. The more he hangs around Susan, the more Joe sees something worthwhile in her, too. And about the time Clarence meets a cute, down-to-earth waitress from his own hometown (Pamela Britton)—well, just imagine that—Joe realizes he loves Susan, but it might be too late to redeem himself, though he flies desperately across Hollywood chasing Iturbi, hoping to beg him to turn his empty promises into reality.

It's a little noodly in its particulars (I said "dragoon," but I meant "the LAPD just randomly arrests two sailors to do a chore"), but even at its lowest it's not much worse than par for a mid-40s musical romantic comedy plot, and at least provides a central conflict that actually can drive a feature-length film that doesn't also make you completely despise its protagonists, since their fake-it-till-they-make-it scheme could conceivably come off, if you don't think about it too hard. Not that despicability doesn't manifest: just wait till you see how they clear the field of a perceived competitor, which takes the form of the jaunty "If You Knew Susie," informing Susan's apparent paramour of her fictional sexual history as what amounts to a U.S. Navy comfort woman. It's pretty nasty and would be nastier still if the narrative were in any sense realistic—Joe and Clarence basically tell Susan's coworker that she's a dockyard prostitute—and if you turned against the movie altogether in the middle of this number, I wouldn't blame you. Still, I laughed at it both times I've seen it, possibly out of sheer surprise at the idea that a song could be this overtly about whoring in a mid-40s MGM musical.

Well, it's certainly never too obvious that the screenplay was written by a woman, based on a short story by another woman; but there's something intriguing about the thing and its time-capsule of 1945, the last year of the war and the peak of America's mobilization, and thus the most pronounced and longest period of gender segregation in American history. It's about sailors on the make, but it's a document of a whole society gagging for it, something underlined over and over, from the homoerotics of the sailors (besides close-ups of Kelly blowing telephones, there's a whole comic beat where Kelly pretends to be a girl for Clarence's education) to the whatever-it-takes zaniness of Joe's plans to get babes—though it's really emphasized when the women start catcalling the men, and the film's concluding note is the ladies echoing the primate grunts that Joe's used as a catch-all for aggressive sexuality. Putting it in its historical context helps me understand why it worked for people in 1945, and maybe even explains how it's so openly sexual; it captures the moment right before the Baby Boom.

There's an even tighter shot, but it might count as porn.

As for the mechanics, they're functional. I personally find it deeply annoying that Lola's mentioned a hundred times and we never see her once; but it's all a reasonably well-built scaffolding for the musical numbers and Kelly and Sinatra's funny interplay. Now, Kelly's miscalibrating his performance a good third of the time—sometimes too high-pitched (literally: Kelly's voice breaks through enough scenes of squeaky whining you wonder if he just hit puberty), and sometimes much too literal (Kelly's rendition of "anger" can feel far too gritty and mean)—but for those other two-thirds, he's fully in-tune with the lightweight material, or, as Joe shifts from dismissing Susan to falling for her, even enriching that turn with soulfulness that is nowhere present in the screenplay.

Sinatra, for his part, though his manchild is a little eye-rolling at times, is meta-funny as a virgin nerd, and he's just actually-funny in his weaselly excuses for conscripting his friend into being his personal dating coach—plus, even if "incel Sinatra" is its own gag, he does look like a nerd, as it's possible you could express his weight in two digits. This looks cool when he's a rail-thin navy-blue shadow dancing in his sailor suit, but it also means he fits the twerpish role the script insists upon (Sinatra plays it as full caricature, too, which seems exactly correct), and, whether Sidney meant to do it or not, it winds up meaningful that about halfway through, the framing and the lighting finally rest on Sinatra in a flattering angle and in such a way to show off his piercing blue eyes, as this is also roughly the moment Clarence slightly deepens as a character (not-coincidentally, it's when he gets nudged out of the A-plot to be the object of someone else's desire in his own B-plot). Needless to say, he sings pretty. As for Grayson, she's a likeable presence as usual—her performance has a lot of doormat in it, even beyond the character-as-written, but there's a brittle, long-suffering, why-would-I-have-ever-expected-any-better quality that works well for the role—and Grayson also sings pretty, though there are enough moments where they clearly were too busy asking whether Grayson could hit those high notes to ask whether she should.

Any real emotional heft is left almost exclusively to Kelly and his dance creations with Donen. This musical is possibly a little inconsistent in approach overall: "We Hate to Leave" and the most pure-fun of the dance numbers, featuring both Kelly and a hard-to-train Sinatra, "I Begged Her," are about the only flirtations with real integration. Even "If You Knew Susie" presents itself as an in-universe performance of a "famous" Navy song; and while Sinatra gets a few croony little numbers that present somewhat like soliloquies (especially "I Fall In Love Too Easily"), he seems to simply be singing out loud. And Grayson doesn't get anything besides diegetic performances. Kelly, however, gets three big dreamy numbers to call his own.

The first and third, being less capable of knocking your socks off, probably get less attention than the second, though they justify their existence better. The first arrives out in a stagebound rendition of Olvera Street in front of the Mexican restaurant that Susan sings at. Accompanied by "Las Chiapanecas," Joe begins to dance to amuse a little girl and winds up working through some feelings of his own. It's one of the most curious pieces of dance in a musical of its era. It looks like it's just cute fluff (and indeed, it's cute), yet its symbolism feels necessary: it's probably not as literal as "this is Joe and Susan's daughter from the future," but the act of amusing and showing affection for a kid (and, if you're Kelly, teaching them some moves) is a wonderfully oblique way of saying "Joe has decided, in this moment, that he's ready to settle down." Kelly's third big routine, set to "La Cumparsita," becomes a swashbuckling Zorro riff as Joe finds Susan on an MGM set, and he pledges his love in a dream she appears to share. This is Kelly-the-multidisciplinarian, adding Spanish dancing to his repertoire, but it's also Kelly-the-athlete, culminating in some straight-up Fairbanksian stuntwork—though what strikes me most is how Kelly didn't bother to conceal the spiraling grooves on the floor that testify to the dozens of times he'd done an especially flamboyant spin before he was satisfied that, finally, it was right.

The second one, of course, is what the film's still best-known for: there are two separate songs, but let us call it "The Worry Song," since this is the good part and also the part that features the film's biggest star at the time of its release, Jerry, of Tom and Jerry, that is, Jerry Mouse (Sara Berner). (The original plan was Mickey Mouse, but Roy Disney was resistant to doing contract work for another studio—which is mysterious to me, as it seems like this would've been a real boon for Disney's collapsing finances.) "The Worry Song" is spectacular, with Kelly and Donen taking everything they learned about dancing with a phantom from "The Alter-Ego Dance" and turning those lessons towards absurd whimsy, creating a dance where a flesh-and-blood man feels like a cartoon and a cartoon feels like a real partner. Technically, it's superb dance and animation—Pasternak and Sidney sent it back to Hanna-Barbera for a second pass when they realized Kelly's reflection was visible on the polished floor, and Jerry's wasn't, and this attention to detail really makes it—and I love the little goofy narrative detail of "that was when I was in the Pommeranian Navy" that justifies Kelly's even-more-adorable second sailor outfit, plus some prefatory frolicking. The biggest problem with it, technically, is that Jerry's freaking enormous, like the size of a dog, but I don't really know how you'd even get around that without just recasting him with Mickey like they'd wanted.

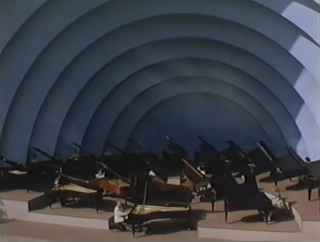

Thus I really, really wish it mattered. Prompted by Joe telling Donald about a king (that's Jerry) who's outlawed dancing because he can't dance, it's not even a metaphor, and it's a dumb fable, and either way I don't think it's fooling anybody: it fits into Kelly's overarching legacy well, but it's as tangential to this film as anything in any film musical. That's fine, but it leaves me in the discomfiting position of not being able to call the best musical number here my favorite. (That status I might accord instead to Sidney's monumental-feeling collage of Iturbi's twenty pianos playing "Hungarian Rhapsody no. 2" at the Hollywood Bowl. Maybe it's just because that's the best song in the movie, but, you know, it's a hell of a sequence itself.)

There's a lot to be troubled by, then—the most nagging thing is that while Anchors never actually feels slow, there's something subtly malformed about a musical romantic comedy that takes fully 139 minutes to deliver the same puddle-shallow plot that any other musical romantic comedy of its era would deliver in less than 100—but also a lot to love. I'm not entirely sure it totally earns my affections—I'm very sure that if I misted up, it only means I'm emotionally unstable—but whether it's Kelly's swell dancing, Sidney's above-average direction, an all-time-great piece of hybrid animation, or the promises it makes to the millions of the lonely people in 1945 still waiting for romance, I dig it.

Score: 8/10

This is a disaster, where the heck is the review of Raising the Titanic?

ReplyDeleteAn unusual request, though I did half-assedly promise such a thing some time ago, so the answer is, "It's on the 'What a Disaster' list, after Hanging By a Thread, Beyond the Poseidon Adventure, Airport '79, City On Fire, SOS Titanic, Avalanche Express (maybe: this one's TBD), Meteor, The Night the Bridge Fell Down, Cave-In, and When Time Ran Out..., but, even though it's chronologically later, before Airplane! and Airplane II: The Sequel, because those seem like the most fitting ways to end the series.

DeleteI was just thinking about it today, in fact, and if the question is "where's the disaster movie series?," yeah, I'm bad at completing things in a timely fashion, but it's never wholly left my mind.