1966

Directed by Stanley Donen

Written by Julian Mitchell, Stanley Price, and Peter Stone (based on the novel The Cipher by Gordon Cotler)

An "arabesque" can refer, amongst several things, to that characteristically Islamic style of decorative art (though it is well-attested in non- and pre-Islamic material cultures), rooted in nonrepresentationalism, geometry, and calligraphy, stereotypically incorporating complex curvilinear and floral patterns; in modern ballet parlance, it likewise can refer to a position in which one leg is lifted, the other en pointe, and arms usually extended as well, and from which no further movement is possible without readjusting your footing. The point is that I'm quite sure Stanley Donen, a smart man and a former choreographer, knew precisely what "arabesque" meant, even if his movie seems to have only a vague idea, unless it's using the term in an entirely new way and conceding that its entire cast of Arab characters is like an Arab, though not one is an Arab, the closest presumably being Sophia Loren, in that she's Mediterranean in complexion (though not this Mediterranean in complexion), and it could be possible that she is of some scant Sicilian descent.* But that title, anyway (succeeding the several boring names used during production, including the rather terrible Crisscross as well as the source novel's own merely-descriptive The Cipher) is, at least, evocative of what Donen's doing with his film, with the term "arabesque" pointing somewhere in the general direction of the geometrically fragmented imagery of this extraordinarily wild-looking motion picture, kicking in with Maurice Binder's op-art opening credits and never really going away for the next 103 minutes, as well as in the direction of a multifaceted narrative that requires its heroine to hold a difficult and untenable position, something different to every man around her, but never able to turn without giving her game away—and, sure, at the fact that the story revolves around a deliciously-convoluted spy plot that's been hatched in the capital of one of the Arab Gulf states or another, albeit definitely not one of the real ones. So that's probably the sole and sufficient reason for the title, and I'm almost certainly overthinking it.

Arabesque, then, begins with that spy plot already in progress, as we arrive alongside Dr. Ragheeb (George Couloris) for his appointment at the optometrist, whereupon he finds that his usual doctor, out sick with "the flu," has arranged for a replacement, and every single thing about Donen's construction of this scene screams—shrieks—that something is horribly wrong, though poor Dr. Ragheeb is of course not aware of the canted angles or the grotesque shot scales or Henry Mancini's nerve-wracking score. They're so oppressive that he's apparently almost aware, but he nonetheless consents to his examination, concluding in the administration of a couple of eyedrops. If freaking out while you wait for violence to be inflicted upon a victim's eyes is your thing—and, you know, it's maybe the most essentially cinematic of horror tropes—this is one superb opening scene, and it teaches you how to watch it in an unusually literal way, for Arabesque's mission is to inflict of all sorts of insane ideas directly upon your eyeballs, too. Perhaps it's a pity that nothing else here ever reaches anything like the same levels of severity and thriller terror again. But only perhaps, since Arabesque might not work as well as it does if it had to continue juggling its tones, and it might well be better that afterwards it sticks with just the one, which is real damn goofy.

That optometrist, it turns out, was but Maj. Sylvester Pennington Sloane, ret. (John Merivale; and for what it's worth, this kooky, comically-bent movie never makes fun of Arabs, but the British are a different story). Sloane's a lackey in the employ of billionaire Nevim Beshraavi (Alan Badel), a clearly trustworthy sort, as you can tell by the way he wears sunglasses even when he's deep inside his mansion and keeps a falcon that he's eager to tell his guests eats only flesh. Sloane's directive with Ragheeb was to secure a certain little slip of paper hidden in the old man's eyeglasses, upon which is written a hieroglyph cipher in what the film will repeatedly assert is "Hittite," which is how Sloane brings it to our man, Prof. David Pollock (Gregory Peck), an American expert in ancient languages presently teaching them to bored university kids in London. Though David initially begs off, he's soon approached by Hassan Jena (Carl Deuring), David's favorite Gulf State prime minister (like any normal American has), who literally snatches David off the street. Once David recognizes him, however, he proclaims what a big fan he is, and is downright ecstatic to have been drafted into the counterintelligence services of a foreign country and tasked with rooting out Beshraavi's evil plans. Accordingly, David accepts the translation job after all, and Beshraavi welcomes him into his home.

But here David makes the acquaintance of Beshraavi's wife, Yasmin (Loren), who begins throwing herself (and her soup) at the stranger in order to get his attention, until ultimately David is compelled to hide in the shower while Yasmin's taking one, with Beshraavi right outside, and the only way out is to pretend to kidnap Yasmin at knifepoint, with the cipher safely in tow, fortuitously hidden inside the watertight wrapper of the candies David's been munching all afternoon. But as you've guessed, Yasmin is not what she appears; and Beshraavi and Jena aren't even the only ones after that piece of paper, and whatever's on it, pretty much everyone who's after it is willing to kill David for it.

By 1966, Donen had been done with musicals for most of a decade, and was most recently coming off of 1963's Charade, which had revived a career then on a downward spiral, seemingly opening up a whole new genre for him to explore: the Hitchcock knock-off. Charade is maybe the last film of Donen's career that has the "unambiguous classic" label attached to it, and it is, indeed, very good. But it is also a little tentative and cautious and stodgy, or at least it feels that way in comparison to Arabesque, his second Hitchcock knock-off (in case "Hitchcock knock-off" wasn't blindingly obvious from the summary, and specifically a knock-off of North By Northwest in the way that Charade is not a knock-off of any one Hitchcock in particular). Perhaps the reason that Arabesque was also Donen's last Hitchcock is because he frankly disliked it, but he never wanted to make it in the first place; he only did so because he did like Loren, Peck, and money. He thought it was stupid, and confusing for its own sake, and a bit of a joke, and of course he was right. Yet confronted with a screenplay he had nothing but contempt for, he used it as a playground for every idea that seems to have crossed his mind; and in one of those great ironies, one of the films Donen was least proud of making wound up being one of the most "Stanley Donen" of them all—and, by my lights, one of the best. I would not like to commit to it being the best because, well, I haven't seen all of them, and Singin' In the Rain is canonically the Greatest of All Old Hollywood Musicals, an opinion I'm not sure I share, though I'd put it in the top three. But in all the ways that Charade is a professional craftsman doing his job and doing it well, Arabesque is the chaotic formalist genius inside Donen, throwing anything against the wall to see if it sticks, and miraculously almost all of it does. So if Charade is your favorite of Donen's Hitchcocks, that's great, but I suppose we must want very different things out of movies.

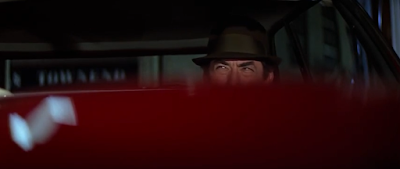

The Robert McGinnis poster hails it as "ultra mod, ultra mad, ultra myster[ious]," and that suggests what a style-over-substance (and, in its protesting-too-much manner, squarely-artificial and humorously-inauthentic) experience we're going to get. It's what comes off so deliriously exciting about it almost half a century down the line: from this distance, at least, the well-funded, try-hard studio psychedelia Donen's plastered all over the screen is a breathtaking joy to behold, nearly every scene offering some bizarre visual trick or offbeat character tic to put it over as a film reeling with the intoxication of its own who-gives-a-shit subterfuge. It could be easy for this to devolve completely into a list of cool shots and cool montages, and I will indulge that impulse somewhat, though I'll only try to hit the highlights, starting with Donen's rad introduction of Yasmin, who is always an excuse to either drape Christian Dior creations over Loren's body:

Much of it is a late 60s spy comic turned into a film, every frame not a painting but a panel (or several panels, even), delivered with trippy ornamentation and high-impact compositions; and somehow this is the feeling that persists even though there's a significant amount of handheld mobile camerawork done with innovative new suspension rigs. There are setpieces of substantial thrills and violence, and the one where they blow up a helicopter is probably the least of them (though it's still quite good), outshone by the primary-colored farm equipment that Beshraavi attempts to run over poor David with in a field of tall grass, as well as an electrifying confrontation with a wrecking ball and an impressionistic, jaggedly-cut chase through a zoo concluding in a deadly confrontation at its aquarium. And all along Donen is taking his career-long pursuit of cinematic collage right up to its limits, frequently tiling his frame with repeated imagery and picture-in-picture, but this time without resort to much (I think literally any) splitscreen technique, and only one optical effect that I can recall. Rather, most or all of it is totally in-camera, ranging from something as aggressive as projecting day-glo letters onto a murder victim's face or Beshraavi worshipping Yasmin's feet in that endless chamber of mirrors, to something as comparatively subtle as that aforementioned field of grass, or a long tracking shot of a car reflected in shop windows.

It is both exhausting and exhilarating to watch, but what grounds it—and what makes it a minor masterpiece—is, remarkably, its performances. In no sense are Peck or Loren playing psychologically real people, or even proper action-adventure characters. They are damned near just playing Gregory Peck and Sophia Loren in the process of having fun making a movie together, the latter photographed with completely-unmotivated and absolutely-permanent dramatic glamor lighting by cinematographer Christopher Challis that rides the tightest possible line between mystique and chintz, while Loren laces Yasmin's expressions with a keen awareness of her own sex symbol status, full of perpetual self-amusement at the multitude of men she's betrayed, correctly reasoning that for the most part they want to fuck her way too much to kill her. Whereas Peck gives what I think might be the single most enjoyable performance I've ever seen him give, animated by a ton of fun dialogue between him and Loren, though he's also admirably willing to risk getting his head caved in by a two-ton thresher.

I've warmed on Peck: I've always known that his limitations were serious ones, and those limitations could practically tank an entire movie if you misused him (e.g., Roman Holiday, David and Bathsheba), but if you deployed those limitations to define his character (e.g., The Yearling, The Paradine Case), or better yet, wrote the character so he actually knows he comes off like a smug stick-in-the-mud (e.g., The Big Country), he could be capable of really impressive work. Even leaving that aside, David Pollock is the most appealingly loose and wacky and funny I've ever seen Peck be. But Donen (or just Peck himself, having spent a couple of decades figuring out his screen persona) uses him for even more interesting ends. David is like an automatic parody of the idea of "Gregory Peck plays an amateur middle-aged spy in a sexy espionage romp with Sophia Loren"—for her part, Loren is equally an automatic parody of a honeypot femme fatale—and the good professor, though incarnated in the form of a wooden cube, is simply so endlessly, dorkily enthusiastic about playing at being a fake international super-spy, frequently cracking dad jokes like he's riffing his own movie, that he's a constant pleasure to watch. Though perhaps he's never more pleasurable than when they dose him full of truth drugs, throw him out the back of a van, and we get to behold the astounding spectacle of Peck high off his ass, rendered in subjective double-vision, and apparently having gotten it into his mind that he's a matador and the oncoming traffic are bulls.

There really aren't very many misses in this film, stylistically or even narratively—I've pooped on the screenplay, but honestly I think it's quite good at capturing the sheer comic absurdity of lookalikes and assassins and skullduggery and all these agents leading double- and triple-lives, and the twists into twists into twists into twists (like an arabesque, amirite?) are surely their own reward—but even the one really flummoxing moment, where Donen does lose track of his storytelling in the midst of frivolous self-indulgence, even that's saved by the congeniality of his leads. Though if somebody would explain to me what's even happening in that scene with the Coldstream Guard, I'd be grateful. (The guard lives up to his regiment's reputation by remaining impassive in the face of Loren being zanily flirtatious, but then Peck whispers something in his ear and, I don't know, I think he dies? My best guess is that "it's a gay joke," but it is dizzyingly unclear, and not in the deliberate way of everything else in the movie that's dizzyingly unclear.)

In any event, Peck and Loren alike, in their disparate ways, are an immense delight, with a surprisingly strong rapport (shockingly good chemistry, but maybe even more shockingly good comic timing), and Peck in particular being so desperately uncool that he wheels back around to being actually cool, because Peck very well knows he's uncool. If it therefore winds up being a parody of all those similar Cary Grant roles, where he thinks he's so fucking cool, well, I heartily approve of that, too.

Score: 10/10

*Generous application of bronzer has never been best practice, even moreso for a film made in 1966 Britain than in 1966 America, and thus worth mentioning, but it's also easy to get ahistoric about it, forgetting that in the mid-century David Lean would be comfortable casting Lebanese-Egyptian Omar Sharif as a Russian and Moustafa Akkad equally comfortable casting Mexican-American Anthony Quinn as the Prophet's uncle. Without denying that darker actors faced active discrimination (which to my mind is the more salient problem here), the non-whiteness of Middle Eastern peoples doesn't appear to have been perceived nearly as firmly as today. I largely attribute this to the problems of Zionism, as well as on American reactions to September 11th. But neither of us are here for sociology & politics, so in that spirit, let us discuss instead how Arabesque was also the French name for Murder, She Wrote. Why?

Why will you not review "Raising the Titanic"?

ReplyDeleteAs previously noted, because it's behind 9 other disaster films on the list.

DeleteWhat a disaster.

Delete