1979

Directed by Alvin Rakoff

Written by Jack Hill, Dave Lewis, and Céline La Frenière

There are a lot of funny industrial idiosyncrasies to the disaster cinema of the 1970s: for example, the way it came in distinct waves, glutting years like 1974 with disaster films while leaving others practically devoid of any major entries (1973 has none at all, while 1975 and 1976 have but The Hindenburg and Two-Minute Warning, respectively); or the way that Airport and The Poseidon Adventure's all-star (sometimes "all-star") casting model ensured that disaster films would be defined, uniquely in the annals of popcorn cinema, by old age, which I've mentioned is one of my personal favorite things about it. But the real paradox of the movement is that even as it (very blatantly!) entered its commercial, critical, and artistic decline, it proliferated. So here we are five films deep into the final year of 70s disaster cinema, which is maybe two-thirds through.

And one vector of that proliferation brought the disaster film, at last, to Canada. This was natural enough, as Canada had been ramping up its film production during the previous decade, with government subsidies intended to nurture Canadian film having begun all the way back in the 1950s, and 1979 is roughly the moment that Canada can be said to have finally established a national film industry of any genuine significance. Now somebody wanted a piece of that American disaster dollar, whether it was still there for the taking or not; the result was City On Fire.

It is, perhaps predictably, difficult to piece together its production history with certainty, though my supposition is it began with its American executive producer, Sandy Howard, who came to Harold Greenberg, owner of Astral—at the time perhaps the closest thing Canada had to a "prolific" film company—with an idea. I suspect, at least, that it was Howard's idea, because it's too perfect not to be, for City On Fire is akin to Howard's twisted autobiography: you see, in 1979 Howard had just gotten back from an involuntarily-prolonged stay in Greece thanks to an explosion on the set of Sky Riders, which left a Greek crew member dead and eleven others injured, and, upon his return, Howard was $250,000 poorer, thanks to the bribe/settlement he'd offered the Greek government on behalf of his subordinate whose (alleged, I suppose) negligence had led to the accident, and who was facing actual prison time for it. City On Fire, meanwhile, is about an embattled mayor, repeatedly accused of corruption in association with a new oil refinery, latterly faced with managing the disaster up-close and personally thanks to a psycho refinery employee who blows the damn thing up because his boss was, essentially, too nice to him. Co-writer and famed exploitation filmmaker Jack Hill had been hired to write a never-produced sequel to Sky Riders; but that job segued immediately into this, and it's really tough to resist the implication there.

Despite this substantial cloud, Greenberg liked the idea enough to put his money into it, with the customary assistance from the Canadian Film Development Corporation, and assigned arguably the most important Canadian producer of his era (The Brood, Scanners, Visiting Hours, and Videodrome), Claude Héroux. The alternative, anyway, is Bob Clark, and the only reason I'm not fairly sure that the $3 million spent on City On Fire did not enshrine its production as the single biggest-budget Canadian movie until that point in history (and probably for some time thereafter) is because Clark's Murder By Decree came out slightly earlier and cost rather more.

Of course Murder By Decree was actually made in London. City On Fire was not. It is thus in some ways the ultimate Canadian blockbuster: noticeably expensive but not as noticeably expensive as its American version, shot in the most featureless stretches of Montreal, with second-unit footage of Toronto mixed in for even more anonymity, pretending to be in "the United States of America," and, assuming you didn't recognize a few impersonal modernist skyscrapers specific to those cities, you'd only notice because, in grand Canadian style, it so obviously wants you to think it's happening nowhere in particular. (Which is the explicit theme of the film: "What happened to them could happen to you..." the poster tagline begins, and I like to think Howard wrote that himself.) Also like any good Canadian genre film, City On Fire stretches its dollars much further than its American counterparts; the same way Canadian slashers and Héroux's own horror movies often feel more generously-budgeted than they were, thanks to clever location shooting and just plain good management, City On Fire competes intelligently, if not quite directly, with American productions five or six times its size.

It's a pity it didn't perform that well, because based on budget, the American equivalent should be Avalanche, and it isn't; there is not, in fact, any American equivalent (the closest in approach is Two-Minute Warning, but Two-Minute Warning is much less competent at it), though in terms of subject matter, of course it's hard not to compare it to The Towering Inferno. Yet City On Fire is unusually experiential even for a disaster film in the 70s, when the genre was readier to tilt toward pure survival thrills than it ever had been before or would be again. It is about fire to a downright shocking degree. The Towering Inferno had to make time to be about the hubris of man and the tense camaraderie of movie stars. City On Fire has no priority except setting objects and people aflame.

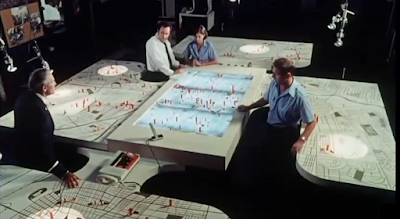

It begins as many disaster movies do, with snippetty introductions to a host of characters, many of them familiar faces—Héroux managed the usual all-star cast, even if fully three of those stars wind up sealed off in their own personal bubbles (the movie makes this work, and I do not mean this as a snide criticism)—and, indeed, all the most familiar faces are most recently familiar from other disaster movies. So in turn we meet Mayor Dudley (Leslie Nielsen), alcoholic newswoman Maggie Grayson (Ava Gardner, which to some degree means literally repeating her performance from Earthquake, though she's thankfully given more than just an absence of dignity here), Nurse Harper (Shelley Winters), and Fire Chief Risley (Henry Fonda). In fact, we meet Risley first, during Fonda's daytrip to Montreal and in the only scene he shares with any character who meets anyone else in the movie, this being his son, following in his dad's footsteps, Fire Captain Risley (Richard Donat). Otherwise, Chief Risley communicates solely by telephone from his tricked-out command center in a surprisingly mod firehouse that uses a neat tabletop wargame to track the blaze the movie will soon provide. As I said, it makes its cobbled-together cast work much better than it should.

I guess it also resembles a swastika, but I think we can assume that's accidental.

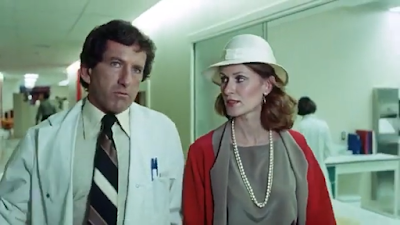

From this swarm, two figures emerge as the most "important": the first is Dr. Frank Whitman (Barry Newman), the cranky supervisor of the shoddy hospital that Dudley's built (we meet Whitman after he accidentally bangs the new nurse who starts her first day later this morning, oopsie-daisy—I'm actually pretty certain he'd have a sexual harassment case against her if his job hadn't burned down); the other is millionaire widow Diana Brockhurst-Lautrec (Susan Clark), who's having an affair with Mayor Dudley, but is presently on hand at the hospital to receive a tour, thanks to a generous donation. I have left out one very important character, however, a recently-disgruntled employee of the local oil refinery, Herman Stover (Jonathan Welsh). Offered a transfer to a white-collar division of the plant based on his aptitude scores, Stover angrily rejects the promotion, insisting he stay where he is in maintenance, and demanding he be made foreman. His boss tells him, politely, to take his ingratitude and entitlement and fuck off, and he takes it extremely, extremely poorly, using his last day on-site to sabotage literally every single part of the refinery he can before walking off the grounds with a giant smile and his severance check while the refinery more-or-less vanishes off the face of the planet in a giant cloud of fire behind him.

None of this ever takes on the shape of a plot, and I could see why that might have annoyed people (City On Fire is generally considered "bad," but, hey, aren't they all?). Now, it's careful to establish all sorts of set-ups for a plot, like the corruption of the mayor, or the psycho maintenance man's obsession with Brockhurst-Lautrec, who was once his high school crush, or the skulking paparazzi who have photographic evidence of Brockhurst-Lautrec's scandal with Dudley, or Fire Chief's presumed concern for Fire Son. It does not give a shit about any of this, and every one of these elements falls away eventually. (The closest it gets to an arc, really, is Gardner's anchorwoman managing to report through the disaster on national television, despite being shitfaced drunk, thanks to the help of her fraying producer, James Franciscus.) But the mayor is destined only for anonymous gruntwork heroism, trapped at the hospital with an inappropriate skillset and doing what he can; I don't quite remember what Fire Chief Risley's son, as a specific fireman, even does after the refinery explosion, though I imagine he must be present throughout; and no one discovers, or is even in a position to care, about the saboteur's crimes. They're too busy with the dead (and this disaster film has a staggeringly high body count—besides the inumerable onscreen deaths, a figure of 3,000 is mentioned, and from its constant casual display of destruction and death, it legitimately feels like it). The film claims that Dr. Whitman and Brockhurst-Latrec have some kind of relationship. I don't believe it ever once clarifies what that relationship actually is. Wikipedia's plot summary shruggingly says he's "known her previously." Biblically? It's irrelevant.

So, yeah, you could go entirely the other way on this, but I found it exhilarating. It's a movie about a disaster where the interpersonal subplots just stop because there is no time or energy to waste on personal concerns when thousands are dead and thousands are dying. (The only character who really continues to pursue a personal goal is the saboteur, who in volunteering at the hospital to assist the people he single-handedly massacred also hopes to get close to Brockhurst-Latrec—but of course he's a complete psycho freak.)

Greenburg drafted director Alvin Rakoff for the project, and it represented his return to feature films after a decade in TV; he's probably best-known for his tough sex dramas at the end of the 60s (and in the case of Hoffman, what I mean is "tough to watch, because it's as tedious as it is sleazy"). I'm aware of nothing in his filmography that would suggest "impressionistic disaster film," or even just "disaster film" (you'd think his scores of TV movies would include at least one, but it doesn't look like it); his most recent project, I believe, is a stage production about the life of Doris Day. But he does a superlative job, bouncing us through the cast list in preparation for the disaster and giving us just enough to hang a character on each, and getting the maximum effect out of René Verzier's gritty, unlovely cinematography, all while supplying an anxious personality to the action, continually cutting each shot frames or even full seconds before its expected conclusion, which for starters is just plain nerve-wracking, but also gives this city-spanning disaster a profound sense of endlessness.

And this is what the movie does care about: the setpieces created by fire, and how the interstitial moments are rendered weird and liminal by the imminence of death. (I'm particularly taken by the Pied Piperish game of "follow the leader" Whitman plays with the children to get them to calmly evacuate; another scene involves Brockhurst-Latrec helping an old man take a shit in a wheelchair which is often identified as "comedy," but I think isn't looking for a laugh, but a feeling of absurdity.)

Now, it's best to cut this low-budget movie some slack when it comes to rendering the "city" part of its title; thus I'm happy to leave aside the dubious bluescreen modelwork and awful background compositing. The film more than compensates for this by absolutely overdelivering on its promise of "fire," and there might be more flamesuit sequences in this film than in any other movie I've ever seen. The truest heroes of City On Fire, then, were stunt coordinator Grant Page and his stunt artists.

A prefatory sequence bluntly establishes the film's goals, whereupon Rakoff and Page just go out and burn down some real fucking houses in the cheapest part of Montreal, trees swaying in the smoky breeze behind them, whereupon they take one of Page's stuntmen and throw him through a floor, evidently just to set the mood. (Perhaps it's not that surprising, then, that Howard killed a guy on his last film, though at least nothing I've seen indicates that Rakoff and Page failed to run a tight ship here.) The final action occurs on what is much more obviously a set (you can, for example, see the matte line during its earlier establishing shots), but it's a vast and sprawling set, and when it becomes a gauntlet of fire you feel every lick of the flame. (And my favorite moment in the film comes in this climax, so good I consider it a spoiler to openly describe it: Whitman, last to leave his doomed hospital, runs out of water pressure to wet his clothes to give him some marginal protection against the flames—because, incidentally, the fire burned through his hose!—and we're given the spectacle of a damned intelligent man, for without missing a single beat he leaps to the ground to wallow in the water he'd previously sprayed on all his patients. This is the moment City On Fire flipped from "real good" to "great," not just the work of brilliant stuntpeople, but engaged filmmakers whose "oversights" were on purpose.) The grotesque aftermath of fire is not avoided, either; the film has one gore shock that'll curdle your blood. It's not even "cool," really, just horrid, and you don't blame the nurse for dropping what she's carrying and weeping; it's a useful reminder that while City On Fire is always disaster-flick fun, its subject isn't, a thought carried through in one of Rakoff's canniest decisions, a treatment of post-disaster refugees camping in a quarry under the closing credits. The most remarkable location, however, is an actual God-damned Shell Oil refinery, so the sabotage sequence where Stover opens apparently every single valve in the plant feels almost unbearably dangerous.

It's maniacally single-minded in its depiction of the fragility of human systems and human bodies, and in its meditation on the tangible reality of flames. But such simplicity is often the mark of a great disaster film: the very anti-complexity that City On Fire deliberately courts—of life's story suddenly halting in the face of harrowing communal disaster—is, in its way, as fascinating as any more richly-tapestried melodrama. The downside is that you could fairly accuse it of being a stuntshow. But here's a secret: I'll always love a good stuntshow.

Score: 8/10

No comments:

Post a Comment