1963

Directed by Sidney Salkow

Written by Robert E. Kent (based on the stories "Dr. Heidegger's Experiment" and "Rapaccini's Daughter" and the novel The House of Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne)

In 1963, Admiral Pictures made its third and final run at exploiting the popularity of AIP's Edgar Allan Poe adaptations with AIP's borrowed Edgar Allan Poe star, Vincent Price. The first, Tower of London, using AIP's borrowed Poe director, Roger Corman, is by far the best and, ironically, wound up the most distinct from the AIP Poes. The second, Diary of a Madman, adapting Guy de Maupassant, had misfired, though it was a very direct knock-off. If it's possible, the third Admiral-Price Gothic horror, Twice-Told Tales, hews even closer to Corman's style. Designed as a three-part horror anthology, it stars Price as a scene-setting narrator, as well as a different character in each individual segment. That should remind you, of course, of another collection of tales—Tales of Terror, or Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror, to be complete—which Corman had made at AIP with Price barely one year prior.

This one, however, isn't Poe (the uncharitable assumption is that the only thing stopping writer-producer Robert Kent from doing Poe directly was shame). Instead, like Diary, it's based on another 19th century author, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and specifically Hawthorne's collection of republished short stories—that's where the title comes from, the rationale behind Hawthorne's title technically making them thrice-told tales here. Or they would be, had they actually been in Hawthorne's Twice-Told Tales, which is true for precisely one of them. Well, it's a neat title, anyway, and, whatever else, Twice-Told Tales represents a very substantial improvement over Diary of a Madman.

It's still an Admiral picture, which means it looks like Hammer if you took two-thirds of Hammer's budget away. Most of its problems stem from its borderline-Poverty Row aesthetic, which affects everything from lighting set-ups that sandblast everything into a gauzy, un-horrifying brightness, to most of the non-Price acting, to Star Trek cave sets that pretend to be crypts (Nathaniel Hawthorne's definitely known for "lots of crypts," right?), to the apparent financial impossibility of doing second takes when, for example, somebody almost knocks over one of the plastic trees. Still, by-and-large, it works, and while there's a definite best (and nothing is great), not a single segment is bad, which is no mean feat for what I'm pretty sure is still only the third English-language (and only the second American) horror anthology ever made; and it distinguishes itself at least a little from Tales of Terror, where Price actually never played the bad guy, by having Price always play the bad guy, though this is not always immediately evident. Kent, freely riffing on just the one story at a time here, does much better with Hawthorne than with his mashed-up Maupassant. It can be clunky (both conceptually and in execution), but it's not a bad way to spend—ah, there's the other thing. For some reason, Twice-Told Tales is fully 120 minutes long—Tales of Terror wasn't even 90—and that's a perfectly valid runtime for three stories to occupy, as even at 40 minutes apiece they're unlikely to drag. You don't consciously notice that length, certainly—though in the absence of much cinematic ornamentation you might unconsciously notice.

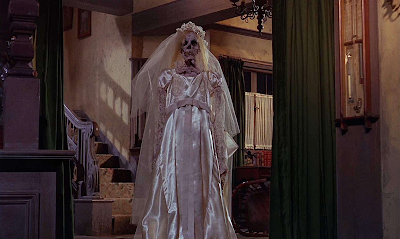

Somehow, it reaches that 120 minutes without any particularly elaborate framing device, but we are invited by Price's voice to check out Hawthorne's venerable tome in a macabre parody of a Walt Disney-style storybook opening; the hand that opens this book is a skeleton. That's dorky but also cute, and apt, too, as Twice-Told Tales is content to be full-on schlock (it also likes skeletons, specifically). The first segment is "Dr. Heidegger's Experiment," and somehow it's not the most loosely-adapted of the three, despite bearing only a passing resemblance to the Hawthorne story. Instead, it uses Hawthorne as a jumping-off point: in the Hawthorne story, the elderly Heidegger is described as having had a fiancée, Sylvia, who died before they could wed, and his grief is implied to be one of the reasons why he does not partake of the water that he's brought back from the Fountain of Youth, though he's eager to test its powers upon a quartet of geriatric guests, albeit, apparently, just to fuck with them. In Kent's retelling, however, this long-lost love (Mari Blanchard) is not just an unstressed detail.

And so do we find Heidegger (Sebastian Cabot), celebrating his 79th birthday alongside his best and only friend, Medbourne (Price), and they are modestly successful at putting a cheery face on the pain and regret of being really old. Heidegger, however, notices the gate to his crypt has been blown ajar following a storm. Investigating, he discovers his fiancée in her tomb, as fresh as she'd been when she died almost four decades before. It turns out to be the water flowing through the cracks in the crypt, bearing some immortality-granting combination of chemicals, and almost as soon as Heidegger has determined it can bring back the rose he would have worn on his wedding day, he's chugging it down. Instead of getting diarrhea, he's restored to, well, Cabot's age; Medbourne, in turn, drinks up and becomes Price's hale-and-hearty 52. But Heidegger's just begun. He turns now to Sylvia's corpse—but Medbourne begs him not to take his experiment to its most natural conclusion.

In fact, Medbourne has been kind of a bitch the whole time, and while "Heidegger" never actually drags, it's the one that has the most redundancy, with the doctor's friend being astoundingly uncurious about their world-changing discovery, constantly worrying and complaining and just-plain whining in ways that even Price finds it difficult to make much out of besides noise. Eventually, this winds up making sense ("Heidegger" has about three times as much narrative as the Hawthorne story, but infinitely more plot). Yet it's strange that they don't take advantage of their star's acknowledged strengths and have Price play the eternally-grieving lover, even if I have no special problem with Cabot's quiet, bored melancholy; by the same token, it's difficult to be thrilled with how clunky and contrived the scenario is, especially when a "38 year quest to acquire the ability to restore youth and life" was sitting right there, and it would've required fewer changes to the text to have gotten there. But once it gets going, it's good and nasty, leading to the kind of reversals you'd expect from any moralizing elixir-of-life story, but also a few other surprises, buttoning things up with a chintzy (but effective) piece of fun Gothic gruesomeness. It's more "Corman Poe" than "Hawthorne," of course; but that's not exactly a sin. (6/10)

Next comes "Rapaccini's Daughter," which is the best thing Twice-Told Tales has going for it (despite not actually being in Hawthorne's collection), and if the score I give it seems to flatten that distinction, it's only because the cheapjack aesthetic imposes a low ceiling. I can't say I'm convinced Kent was always a good screenwriter, but "Rapaccini's Daughter" is top-notch adaptation. It's not even unfaithful—it sticks fairly close to Hawthorne's narrative—but it makes certain additions to the material, and shifts some of it around, so as to tell the same story about different ideas. It's less about meddling in God's domain now (though it is still about that), seizing instead upon a single line uttered by its mad scientist ("Wouldst thou, then, have preferred the condition of a weak woman, exposed to all evil and capable of none?") and building out from there, ultimately coming off more Hawthorne than Hawthorne, at least if your major touchstone for Hawthorne is The Scarlet Letter, which, if you're like me, you read begrudgingly if you read it at all.

In any case, "Rapaccini's Daughter" begins with Giovanni (Brett Halsey), who's recently arrived in Padua for his studies, and has had the bad luck to find a room in a house adjoining the compound occupied by Dr. Rapaccini (Price) and his pretty daughter Beatrice (Joyce Taylor). As we're told upfront, Rapaccini has inflicted a cruel condition upon his daughter, using his mastery of botany and chemistry to modify her blood so that her very touch is poison; she even relies upon frequent infusions from the gross tropical plant they keep in their garden—so egregiously toxic that Rapaccini can't even work on it himself—just to remain alive. Why has he done this mad thing? Because many years ago, Signora Rapaccini abandoned her husband and daughter to run off with another man, and thus has Rapaccini conceived this modification to his daughter's body chemistry as a safeguard against the dangerous feminine passions he assumes she's inherited, rendering her own body her cage. But as Giovanni doesn't know any of this, he falls in love with Beatrice, and she with him. And as Rapaccini does love his daughter, he softens, and perhaps he can come up with a way for them to be together after all, and it turns out Rapaccini being nice is even worse.

It certainly has problems: besides the cheapness—this is the one where somebody almost knocks over a tree—and general ugliness, I'm certainly not sure that the smoke-spouting "acid burn" effect director Sidney Salkow deploys to punch up the horror of poison by making it visible (and audible) is remotely useful, and it raises the question of how she doesn't dissolve her clothes. Perhaps even more importantly, Taylor isn't very good (not even on the level of blunt declamation that Halsey's working on, for Halsey at least has some wonderful reaction shots where he seems to narrow and bulge his eyes at the same time); Taylor, anyway, bites the heads off lines that don't deserve it, and approaches the prospect of a loveless existence with something more akin to tetchiness than anguish. Price at least gets to put some flourish on a villain convinced of his own righteousness but also quite giddily aware of the pettiness of the pleasure he takes in inflicting "corrective" pain on his daughter and her paramour—but it's not really top-shelf Price, either. Ultimately, it's just that Kent's screenplay here is just that structurally sound, with a hell of a pair of twists (the second more fatalistic than surprising, but the first, if you've never read the story, managing the trick of being both completely predictable in retrospect and completely shocking in the moment). I daresay it could've been a feature, though I suppose when I imagine the feature version, I'm imagining an Admiral picture less than I am an AIP one, with Roger Corman exploiting the possibilities of Rapaccini's isolated compound and the phantasmagoria of Hawthorne's imagery. Yet I'm inordinately glad that at least a small-scaled version of "Rapaccini's Daughter" exists, in the form of an updated morality tale that doesn't forget any of the gnarly shocks that were already present in the text. (7/10)

We conclude with "The House of Seven Gables," and forget whether it was in Hawthorne's Twice-Told Tales, what we have here is a 40 minute adaptation of a 400-or-so page novel. (Indeed, a novel that had already had a feature-length adaptation which Price had co-starred in, many years before.) I've been reading along with these 60s horror adaptations, you know, but to review a 40 minute anthology segment that takes little more from the source material than the surnames (not even always the given names!), a house with seven gables, and perhaps a general vibe? Sorry, no thanks. Either way, "Seven Gables" is still an abidingly decent little ghost story. It affords Price one of the grubbiest, most small-time bad guys he ever played in Gerald Pyncheon, who has returned with his wife Alice (Beverly Garland) to his ancestral home in Salem, Massachusetts, presently occupied only by his just-as-much-of-a-jerk sister Hannah (Jacqueline deWit). The house has a curse on it, thanks to the depredations of their Pyncheon forebears: in the 1690s, they stole it from the Maule family by accusing one of them of witchcraft. He was burned, but not before he put a curse upon the Pyncheons and all their progeny. (Or rather, their male line, as Hannah continually and smugly points out.) Gerald's here to try to find the vault the Maules hid somewhere in the house, hoping its contents can revive his fortunes after a lifetime of failed commercial schemes; but pretty much the instant he and his wife enter, weird things start happening, with some spirit attempting to commune with Alice across the gulf of time. This sets into motion events that, in the end, will let this old house rest in peace, or maybe just pieces.

It's... fine! The biggest objection (well, unless you're an architecture snob, because this is one of the least-convincing "colonial Massachusetts houses" ever depicted, short of haunted palaces, anyway) is probably that although Hannah claims that she's searched all over and Gerald will never find the vault, it's hard to believe that she (or anybody) has so much as tried; it wouldn't take you or I even 40 minutes to find it, and this story does not unfold in real-time. It's again more Corman Poe than Hawthorne, thus evil paintings and evil houses; it's likewise obvious that this is where the vast majority of Twice-Told Tale's budget went, and even if "the lion's share of nothing" is still "nothing" (the model representing the gabled abode in establishing shots is hilariously bad), they did manage to render a reasonably effective evil house. The house ultimately strikes out at Gerald in ways that are surprisingly sensational for a 1963 film, with fissures opening up to gush blood, but also in ways that are reassuringly conventional for a crappy Vincent Price horror movie, the specter that sends him into the most profound torment being a disembodied armbone. (And does Kent manage to rip off House of Usher again? Oh, yes, and this time without anything like the excuse Maupassant gave him.) It's also the one segment where cinematographer Ellis Carter seems to remember that objects can cast shadows, and in horror movies, perhaps they should. "Seven Gables" is trivial; besides the whole "house gushing blood" aspect, it's also a rehash of better things. But it's fun. (6/10)

Twice-Told Tales is relatively inessential overall—there's barely any comparing it to Tales of Terror, whereas even comparing it to the Amicus anthologies around the corner, though I would happily call it better than some of them, the two hours it takes to get through just three stories here means it's more demanding than any of them, and it looks worse than almost all of them. And even its best segment is hamstrung by its production realities (which, sadly, is also true of its bleeding house). But you could find yourself watching worse horror anthologies (you don't even have to leave 1963; Black Sabbath is worse). As far as its format goes, then, it's a modest success, but a success nonetheless.

Score: 6/10

Reviews in this series:

The Fall of the House of Usher (Corman, 1960) Night Tide (Harrington, 1961)

Pit and the Pendulum (Corman, 1961) Premature Burial (Corman, 1962)

Tales of Terror (Corman, 1962) Tower of London (Corman, 1962)

The Raven (Corman, 1963) Diary of a Madman (Le Borg, 1963)

The Terror (Corman et al, 1963) The Haunted Palace (Corman, 1963)

Twice-Told Tales (Salkow, 1963) The Comedy of Terrors (Tourneur, 1964)

The Masque of the Red Death (Corman, 1964) The Tomb of Ligeia (Corman, 1964)

War-Gods of the Deep (Tourneur, 1965) Die, Monster, Die! (Haller, 1965)

Blood Bath and iterations (Rothman et al, 1966) Witchfinder General (Reeves, 1968)

Curse of the Crimson Altar (Sewell, 1968) The Oblong Box (Hessler, 1969)

The Dunwich Horror (Haller, 1970) Scream and Scream Again (Hessler, 1970)

Cry of the Banshee (Hessler, 1970) The Abominable Dr. Phibes (Fuest, 1971)

Murders In the Rue Morgue (Hessler, 1971) Dr. Phibes Rises Again (Fuest, 1972)

Theatre of Blood (Hickox, 1973) Madhouse (Davis, 1974)

Thanks for these delightfully exhaustive reviews. This one sounds like it influenced Crimson Peak.

ReplyDeleteThanks so much! And, oh yeah, they *all* influenced Crimson Peak.

Delete