1990

Directed by Zhang Yimou and Yang Fenglian

Written by nobody, apparently? (based on the novel Fuxi Fuxi by Liu Heng)

Ju Duo was Zhang Yimou's follow-up to Red Sorghum, but it is not Zhang Yimou's second film—obviously not if you mean "the films he worked on," as we lengthily discussed last time, but not even if you mean "the films he directed." In between his first film and his third, he made 1989's Codename Cougar, which has practically been memory-holed since, perhaps because there's nothing stereotypically "Fifth Generation cinema ready for export to the Western arthouse" about it. It's just a straightforward commercial proposition (it's an airplane thriller), dismissed by the scholars who've seen it with a jaunty "who cares?", and it's not even included as a standard definition special feature in the shiny new box set released by Imprint a few months back that bears the magisterial title of Collaborations: The Cinema of Zhang Yimou & Gong Li, which wouldn't be annoying if Codename Cougar didn't fucking star Gong Li, meaning that they did 89% of their job, and a great job they did, but for some reason didn't finish it. Fundamentally, the purpose of such things is to make money, I get that, and, ironically, Codename Cougar doesn't move one single extra unit; but there's a veneer of film preservation and more than a veneer of film appreciation to the exercise, and the idea that they're selling, ultimately, is that for a mere couple hundred dollars (Australian dollars!) you can be an amateur scholar of Chinese cinema yourself. Well, scholars sometimes have to watch shitty movies, and more importantly, I'd rather decide for myself what "matters." Plus, hell, I like airplane thrillers.

Obviously, I bring this up mostly to hear myself whine, but also to note that Zhang was rejoined on his third film by his co-director from Codename Cougar, and what that means, I can't say: the Ju Dou blu-ray offers a half-hour or so of scholarly discussion about the film, and if they so much as mentioned Yang Fenglian's name, I missed it. I surmise this means his contribution must have been minimal, maybe even just administrative, and considering the affinities Ju Duo has with the rest of Zhang's early filmography, that's certainly plausible; then again, those scholars don't mention the 1.37:1 aspect ratio once either, and considering this is absolutely unique in Zhang's filmography and therefore seems worthy of comment and explanation, maybe even scholars can overlook things.

But now we're touching on the film itself, so let's begin: Zhang Yimou's third film is (presumably) also his first masterwork. As the decades have accumulated, early Zhang has been pared down somewhat to the sentiment "Raise the Red Lantern and, oh right, several other movies," and that's not entirely fair—it's not entirely unfair, either—but that one gets all the attention. Ju Dou has never deserved to be eclipsed by its own follow-up; and for my part, I'm not sure if it's not actually the better film. It is not as austere, nor as jaw-droppingly beautiful, but it's at least competitively beautiful, and it also depends less on repetition (it's half an hour shorter and you can definitely tell); most of all, it's a hotter-blooded film. (Plus when its characters are obliged by its story to do stupid things in connection with their reproductive systems, in Ju Dou it's not a pivotal plot point, and arguably not quite as stupid.) Believe it or not, it may even use its symbolic color scheme better, even if it doesn't use color as boldly. In any case, it's terribly close, and it's a tremendous improvement over Zhang's last "real" movie, again maybe not as flatteningly pretty as Red Sorghum's first or final thirds, but at least it's a movie that you don't need to disaggregate into distinct sections in your desperate bid to find it likeable. For all that, it's hard to disentangle Ju Dou from those two films, as it sees Zhang essentially going back to the well he visited in Red Sorghum and would return to again in Red Lantern, a variation on what seemed to be his favorite theme during these years—he practically made "Gong Li is a sad woman in an ugly marriage" its own subgenre—and while Ju Dou at least doesn't open with the exact same visual as Red Sorghum and Red Lantern do, a close-up of Gong's face, one almost wishes it did, as to better establish the identity between the three, not to mention Curse of the Golden Flower years down the line.

Instead, it begins with Yang Tianqing (Li Baotian) returning from a sales trip for his adoptive uncle Yang Jinshan (Li Wei), owner of what looks like a reasonably prosperous dye factory in a small town somewhere in 1920s China. We mark Jinshan as a skinflint old bastard immediately, who plainly conceives of his "nephew" as a slave, yet Jinshan has splurged on one recent purchase, and that's Ju Dou (Gong), a brand new wife, young, gorgeous, and presumably fertile. Jinshan of course is none of these things, though this did not stop him from blaming his previous two wives for failing to give him children and torturing them to death. That's the story we hear secondhand, and one tends to credit it, because as soon as Ju Dou has arrived, he's beating and berating her, too. As we learn later, he can't even complete the basic act of child-making, so he spends their nights together grinding sick satisfaction out of hurting his bride instead. Tianqing has noticed how pretty his new "aunt" is, and she's noticed him noticing; but he's also noticed the bruises and the screams, and it might be as much compassion as lust—maybe just their mutual humiliation under their mutual owner—that brings them together. In short order, Ju Dou's pregnant after all, which complicates things, though Jinshan can only save face by accepting the child as his.

Thus he bides his time—too long, perhaps, because in a stroke of fortune for the two adulterers, Tianqing finds Jinshan's broken body outside the town, victim of a bandit attack that's crippled him. That leaves Ju Dou and Tianqing effectively in charge of the shop, the child Tianbai (eventually Zheng Ji'an as a teen), and Jinshan's welfare. It also gives them the opportunity to forge something behind closed doors that looks like a marriage of their own. The bad news is that when Tianqing considered leaving his uncle to die, he should have gone with his first instinct. That brings us about halfway through the film, and four or so years into the fourteen or fifteen years that Ju Dou chronicles in the lives of these ill-starred lovers, and I want to emphasize that things don't just stop happening here. Indeed, things somehow get worse for Ju Dou and Tianqing.

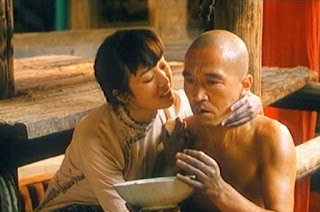

This is a much fuller two-hander than the label "starring Gong Li" might indicate: of her and Zhang's first three melodramas together, this is the only one that really has a male lead; in Red Sorghum they're playing ideas more than they are character, and Red Lantern is the Gong Li Show, maleness being more of a shadow defining the shape of women's lives than an active presence. But here Li Baotian's performance is at least as important, and at least as good (or he has the most bleakly devastating moments, above all his reaction when Ju Dou jokingly asks him if he'd dare respond if Tianbai were to call him "father," and in Ju Dou "the most tearjerking performance" is more-or-less the same thing as "best"). In fact, we spend at least a quarter of the movie with Tianqing as our protagonist; it's a while before Ju Dou joins him. It's a while, in fact, before we even see her, or Tianqing meets her—in a bashful, expertly-framed encounter where his head peeks over the stairs to behold the love of his life, and the very fear that flashes across his face is, it seems, what initially charms her. It even suggests that maybe it's not so bad that he peeps on her while she bathes. The second time, anyway, she lets him, though now she can only offer an image of brutalization.

Ju Dou is a series of high-impact moments like this, agony and ecstasy alike—agony predominates, and let's not give too much away, but it climaxes with Ju Dou in a malestrom of flame—but all building upon one another until the only appropriate way to end it would be with cleansing fire. It creeps right up to the edge of noir: it really would've been a better outcome for all involved if they could have somehow done away with Tianqian's abominable uncle. (For the record, the source novel was changed to remove Tianqian's blood-relationship to Jinshan. How this makes a difference is mystifying.) The problem is they can't just kill him, not solely thanks to Tianqian's strained morality, but the society that, as Tianqian says, wouldn't just look down on their relationship, but kill them for it. Thus even when Jinshan is humbled, even when he's trapped in a bucket, he looms over his wife and nephew, maintaining power as the owner of the shop, the head of their household, and the recognized father of Tianqian's son. Ultimately, any hope of escape is stripped away—even the dubious pleasure of avenging the sins that Jinshan had previously lavished upon them fades into nothing (and it's worth mentioning that for a good stretch, Ju Dou is a nerve-jangling thriller as murder keeps coming up, though maybe the nastiest little thing in the movie is the exclamation of a passerby who sees Tianqian bathing his disabled uncle and proclaims him more piously loyal than a son—and it occurs to me on this viewing that she's heard the gossip and she's being as sarcastic as the movie is).

But as the first words that Tianbai speaks are to call Jinshan "father," Jinshan's already won. It doesn't matter now, really, whether Jinshan dies, or whether they tell Tianbai the truth. The vast machine of society will inflict Jinshan's punishments upon them even beyond his grave; for his part, Tianbai will never understand. There's truly something wrong with Tianbai, after all: he's both the recapitulation of his legal "father," and somehow even purer in his malevolence, a ball of murderous shame who knows that he's a bastard (and that everybody else knows he's a bastard), with only one outlet for that shame and without an ounce of pity for his parents' circumstance. If his course could've been changed, or if anyone's could've, that moment passed long before the film's over and possibly before it began. Which is what Ju Dou is fundamentally about: there's probably an autobiographical reading of it, given Zhang and Gong's relationship (and the divorce Zhang's wife wouldn't give him, though I'm unsure if the chronology holds up there), but there's something to Tianqian being forty, and the way that Jinshan has already used up his life the way he'll use up Ju Dou's. They're two prisoners confined to a small box that's overseen by monstrous jailers, but at least they had the good luck to be confined together. And for all the tragedy, it is good luck, and it's annihilatingly sad to see in Li and Gong's faces, seemingly aged beyond their years, that they know they were lucky to steal even as much happiness as they did, and they don't quite regret it.

So that Academy ratio, then, if it has a reason, might be to provide a greater sense of verticality for the principal visual motif of the film, the bolts of cloth hung high from rafters and sailing through the towering space of the Yang dye shop, which we find frequently photographed with blasts of backlighting, kind of like a hair metal video, which maybe isn't the most flattering comparison but it helps situate Tianqing and Ju Dou as mythic figures, laboring at mythic work, stand-ins for a million tragedies not so much different than their own. (Zhang, as is Zhang's wont, came up with the visual idea first and did his research second, sticking with it even once he learned it resembled 1920s dye factories in no way whatsoever.) There's obviously something evocative about color streaming up and down the frame, and while it's not a totally rigorous scheme Zhang's come up with, it's an inordinately intelligently-applied one. Curiously, the colors aren't as saturated as they were in Red Sorghum (despite the same cinematographer, Changwei Gu), at least not usually. This happens mainly in just a few shots, especially of a wet bolt of red cloth flying through space and into red liquid, coming off almost disquietingly biological; that's the key image, sex and violence all at once, the cause and the consequence. (And Ju Dou very much confirmed that Fifth Generation cinema would be frankly erotic. If the sex scene with the red dye didn't do it, then the adult breastfeeding scene did. It helped that it was effectively a Japanese production with Chinese names attached. Even then, the chill in the air after Tianenmen caused Zhang and Gong to rethink a topless scene.)

Well, besides dangerous red (maybe sexy yellow?), color is simply happiness and hope—if it's complex, it's in the various saturation levels and the specific narrative valence some hues bear—but color finally recedes, the last third of the film defined almost exclusively by color's marginalization, especially a funeral that is done with striking white costumes and white banners and ten thousand white paper coins, each as worthless as a dream. And then maybe the single saddest shot in a very sad film finds Tianqian and Ju Dou arrayed in blacks and grays, hiding away from their hateful son, once again pretending at being husband and wife.

Here, he offers her color—a pale red scarf, a piece of light blue cloth, the same colors that flew from the rafters during the first time they bonded over their shared fate. Now he can bring only this: small tokens from a life that wasn't, overwhelmed by the grimness of the life that is. It's love surviving on scraps of memory, and the memory was painful in the first place.

Score: 10/10

No comments:

Post a Comment